The Wallowa Mountains near Enterprise, Oregon. Photo George Wuerthner.

The Blue Mountains Complex of Oregon stretches east to west from the Snake River to the Cascades. The Blue Mountain Complex is made up of sub-ranges, including the Wallowa, Elkhorns, Strawberries, Aldrich, and Ochoco.

These forests must be preserved for biodiversity, and carbon storage. Notwithstanding that the Eagle Cap Wilderness, Oregon’s largest protected area, lies within the complex, the Blue Mountains Complex still has some of the lowest percentages of designated wilderness or other protected landscape of any ecoregion in the state of Oregon.

Protected landscapes like wilderness preserve water quality, sustain biodiversity and are critical for carbon storage.

Trees larger than 21 inches only makes up 3% of the forests in eastern Oregon, but they account for nearly 50% of the above ground carbon

Due to logging, clearing for agriculture, and other factors, researchers have found that only 3% of the trees in eastern Oregon exceed 21 inches. Yet this small percentage of the forests contains nearly 50% of the above-ground carbon storage in the region.

Furthermore, larger trees accumulate carbon at a more rapid rate than smaller trees, so maintaining as many large trees—either alive or even dead—in the forest ecosystem is critical to keeping carbon in the forest ecosystem.

In 1936 86% of the forests in the Blue Mountains were considered old growth. Pine Creek, Hells Canyon NRA. Photo George Wuerthner

A 1936 inventory in the Blue Mountains (today’s Malheur, Ochoco, Umatilla, and Wallowa- Whitman National Forests) found that forests containing a significant proportion of ponderosa pine occupied about 80% of commercial forestlands. The great majority of pine forests consisted of old growth (86%). By the mid-1960s, however, the proportion of commercial forests…had dropped to 40%, primarily due to logging, a loss of half over a 30-year period.

Wenaha River, Wenaha Tucannon Wilderness. Photo George Wuerthner

To protect large trees, in 1994, the Forest Service enacted the 21-inch policy, known as the Eastside Screens, which prohibits logging trees larger than 21 inches.

However, in recent years, the Forest Service, along with its collaborators, has recommended the elimination of the 21-inch rule. The Trump administration approved the modification of the Eastside Screens which would allow the logging old and mature trees throughout eastern Oregon. A lawsuit challenging the decision was filed by six conservation groups and the Blue Mountain Biodiversity Project is challenging the Fremont Winema NF on similar grounds.

In particular, the Forest Service wants to target grand fir for removal, even though the species accounts for the greatest carbon accumulations in eastern Oregon forests.

For a good analysis of why the 21-inch rule should be maintained, arguing that they are biocultural legacy, see this overview by Dominick Dellasalla and William Baker.

Old growth ponderosa pine along the Imnaha River, Wallowa Whitman National Forest, Oregon. Photo George Wuerthner

The Forest Service and its supporters suggest that eastern Oregon’s forests “need restoration”. Unfortunately, the main way they accomplish this restoration is with bulldozers, chainsaws and clearcuts in the name of wildfire prevention.

Research suggests that chainsaw medicine (logging) often enhances fire spread by opening up the forest for greater wind penetration and drying, both of which are major factors in large wildfires.

Some researchers question whether thinning and other “active forest management” are really effective to limit high severity blazes under extreme weather conditions. As they note: “Policy and management have focused primarily on specified resilience approaches aimed at resistance to wildfire and restoration of areas burned by wildfire through fire suppression and fuels management. These strategies are inadequate to address a new era of western wildfires.”

Dellasalla and Baker suggest that: “Fear of megafires is driving forest management policies throughout the region that call for reducing tree density and removing large shade-tolerant firs thought to increase fire hazard, even though firs were historically common in Eastside mixed-conifer forests.”

.

View of Blue Mountains region from Monument Mountain Wilderness, Malheur National Forest. Photo George Wuerthner

One of the issues of debate is the historical frequency and severity of wildfires in the dry forests of eastern Oregon. Some researchers suggest that frequent wildfires kept fuels low, forests more park-like and high severity fires were unusual. They usually advocate more chainsaw medicine (logging) to reduce forest densities.

A fire scar on old growth ponderosa pine, Lookout Mountain Proposed Wilderness. Ochoco National Forest. Some researchers argue that fire scar studies misrepresent the historical fire conditons. Photo George Wuerthner

By contrast, other researchers using Government Land Office survey reconstruction showed that only about 40% of the Blue Mts. had exclusively low-severity fire, with 43% mixed severity and 17% high severity where the majority of trees were killed.

Indeed, Dellasalla and Baker report the reliance of fire scar studies tends to misrepresent the historical fire conditions. As they note: “Limited fire-scar sampling (fire return intervals extrapolated from small unrepresentative stands to landscapes often without reconstructing fire severity) result in fire return intervals that are too short, and misrepresent the occurrence and ecological importance of mixed- and high-severity fires.”

Western larch, Glacier Mountain proposed wilderness addition, Strawberry Mountains, Malheur National Forest, Oregon. Photo George Wuerthner

They go on to say: “This has led some researchers and the agency to falsely conclude that Eastside forests were predominately open park-like pine forests, when, in fact, fire regimes and forest structure and composition were much more complex.”

Another study came to similar conclusions: “These extensive montane forests are considered to be adapted to a low/moderate-severity fire regime that maintained stands of relatively old trees. However, there is increasing recognition from landscape-scale assessments that, prior to any significant effects of fire exclusion, fires and forest structure were more variable in these forests. Biota in these forests are also dependent on the resources made available by higher-severity fire.”

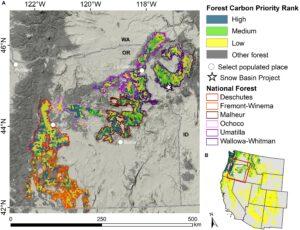

Map showing Oregon forests and carbon priority rank. Much of the Blue Mountains is ranked medium to high.

In a recent paper, Oregon State Scientists and colleagues argue that protecting forests is the lowest-cost climate mitigation option to reverse climate change.

Oregon has the highest percentage of forested landscape of any western state, yet has the dubious distinction of the lowest proportion of protected forest ecosystems.

Old growth ponderosa pine in Joseph Canyon roadless area. Such places should be designated wilderness. Photo George Wuerthner

Currently, only 7% of Oregon’s forests have permanent protection from logging, grazing, and other extractive industries.

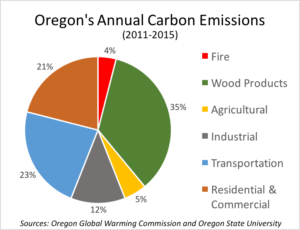

The wood products industry (green) accounts for 35% of the carbon emissions in Oregon.

There is good evidence that an inverse relationship exists between “forest management” and carbon storage with greater carbon losses due to logging and thinning, and a consequent increase in carbon emissions. Indeed, the greatest contribution of Greenhouse Gas emissions in Oregon comes from the wood products industry.

This brings me back to the Blue Mountains ecoregion. It is Oregon’s largest sub-region and contains some of the most carbon-dense forests on the planet. In addition, the ecoregion is a critical wildlife corridor that connects the Cascades to the Rockies.

Silvies River proposed wilderness. Photo George Wuerthner

Unfortunately, in the Blue Mountains Ecoregion, wilderness areas are typically small, with large distances between each protected area. There is a great need for a well-designed, intergraded system of new wilderness reserves with connected corridors. Currently, approximately 2.2 million acres (about the size of Yellowstone National Park) need protection as wilderness, wild and scenic rivers, and other designations that can improve connectivity and ecosystem function across the Blue Mountains.

The North Fork of the Malheur River is one of the many roadless lands in the Blue Mountains that should be preserved as designated wilderness. Photo George Wuerthner

One of the current pieces of legislation that would protect important aspects of the Blue Mountain ecoregion is the Oregon Rivers Democracy Act introduced by Oregon Senators Merkley and Wyden. Writing these senators to support their legislation would help ensure some of this spectacular region gains some permenant preservation. Permanent preservation of all roadless lands in the Blue Mountains and protection of corridors needs to be implemented across all eastside forests.