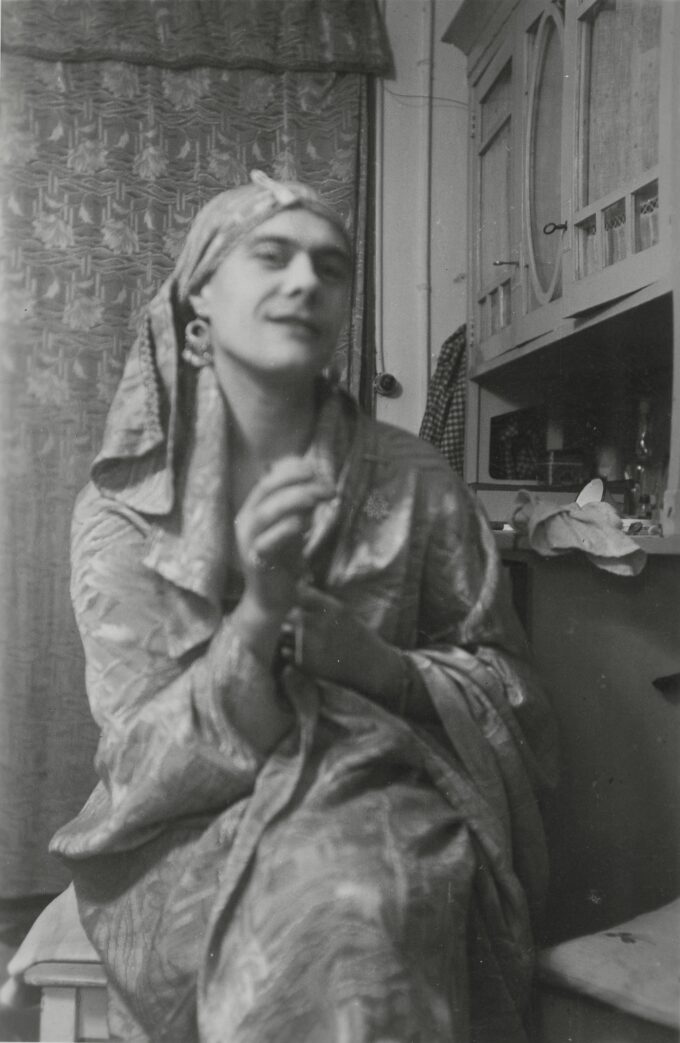

Walter Richter in his kitchen, Berlin 1940, with permission of Landesarchiv Berlin.

In March this year, Trump wannabe Ron DeSantis signed his infamous “Don’t Say Gay” bill, surrounded, for dramatic effect, by a group of young children in neat school uniforms, the kind totalitarian rulers have always adored. Carefully crafted, DeSantis’ photo op was sure to score points with the Fox News faithful, at a time when a record number of anti-GLBTQ measures are making their way through state legislatures. A week or so earlier, a patchily bearded Senator Ted Cruz had mocked fluid gender definitions, a favorite bugbear of the right, when he asked Supreme Court nominee Judge Jackson if she knew what a woman was and then immediately answered the question himself, albeit indirectly. Since everyone, including Senator Cruz, could at any point choose to be a woman, he said, just about everyone could have legal standing in any court case anywhere. The result: total legal anarchy, the logical outcome of appointing progressive activists like Judge Jackson to the country’s highest court.

These thoughts went through my mind as I was trying to come to terms with a recent visit to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp north of Berlin, where—apart from Jews, political prisoners, Soviet prisoners of war—the Nazis also held hundreds of gay men, the 175ers, as they were called, since they were arrested under paragraph 175 of the German criminal code. Recognizable by their pink triangles, they were the victims to regular bullying by the guards and sometimes also by fellow inmates. Hundreds of them died, some of them as the result of medical experiments, in which they were injected with hormones or castrated. Between 5,000 and 15,000 homosexuals,mostly forgotten today, died in Nazi camps.

I had traveled to Berlin during spring break, in the grim shadow of the coronavirus, with a group of undergraduates from Indiana University, where I teach. To get to Sachsenhausen, you take the S-Bahn from Berlin to Oranienburg, a flat, mostly charmless German city that saw heavy bombing during the war. The camp, or the small portion that’s left, is a short walk away. For the last few minutes, before you get to the visitors center, you’ll pass by a tidy array of brick houses once built for the SS guards and their families, laid out neatly as if on a Lego baseplate. Whatever nightmares they may have once contained are now permanently held at bay by grinning garden gnomes and cheerful signs announcing that “here live the Müllers.” In 1992, the visionary American architect Daniel Libeskind proposed flooding a vast swath of the campsite, creating a “sunken architectural zone” to be viewed from a network of dikes and, on a remaining piece of land, a building that would accommodate a library, a chapel, mental health clinics, and other public services (but no residential spaces). His proposal went nowhere.

The day we visited Sachsenhausen was a typical early spring day in Germany, slightly overcast and still chilly. The trees poking over the remaining walls of the camp were still mostly bare. Many things have changed, of course, since the spring of 1945, when the SS hastily departed the camp, killing thousands more on so-called “death marches.” The metal gate with the terrifying “Arbeit macht frei” (Work makes you free) is a replica, and there is a spacious visitor center, stocked with publications in multiple languages. Several of the barracks where the prisoners were held are gone (some as recently as the 90s, when Neo-Nazis torched some of the structures where Jewish prisoners were held). A massive Soviet memorial to the Russian inmates of the camp now sits at the center, inadvertently reminding us that, after 1945, when the camp seamlessly transitioned into its new role as a part of the Gulag system, thousands more lost their lives here too, ex-Nazis as well as anyone else targeted by the Soviets.

Yet other things are still the same: the morgue, for example, with its white cabinets and tiled dissecting tables, on which the SS doctors, as brutal as they were inexperienced and ignorant, conducted their final experiments. The remnants of the infamous shoe-testing track are still there—inmates had to walk over different surfaces between 25 and 40 miles a day in ill-fitting shoes made from synthetic materials, an attempt by the Nazis, with the complicity of the German shoe industry, to test new footwear in response to shortages caused by the war. Those who collapsed, if they weren’t dead already, risked getting shot.

The gray, overcast weather, damp and chilly, added to the overall effect of raw despair. Our guide was competent, informed, and empathetic, but, as I was struggling to grasp what had happened here, I fell behind. I instinctively turned away when I saw foot washing stations into which, according to labels affixed to the wall, guards had pushed the heads of prisoners so that they would drown. Death in Sachsenhausen was a daily, hourly reality, part of the routine. Hannah Arendt’s sentences about death camps in The Origins of Totalitarianism drifted back into my consciousness. Written with a steely, fierce, incorruptible brilliance and insight, they still take your breath away: “The real horror of the concentration and extermination camps lies in the fact that the inmates, even if they happen to keep alive, are more effectively cut off from the world of the living than if they had died, because terror enforces oblivion. Here, murder is as impersonal as the squashing of a gnat.”

While my students caught up with their guide, I lingered before a wall of displays put up next to the camp’s death zone, cynically called “Station Z.” There was an entire row of them, a feat of investigative ingenuity, with photos of those who had died here as well as those who had done the killings. Some of these are family snapshots from an earlier life, featuring smiling people in their homes, unaware of what the future would bring, enjoying, as German families still do on weekend afternoons, “Kaffee und Kuchen,” coffee and cake; others showed the guards in full uniform, wearing boots and carrying rifles, their demonstrative fierceness obliterating the emptiness of their eyes. Many of those who worked here had tried and failed at something else, their education having rarely gone much beyond elementary school. Right next to some of the photographs of prisoners were pictures of their arrest records, court verdicts, or death certificates, a trail of bureaucratically sanctioned violence.

One of these photos stopped me in my tracks. According to the accompanying text, this was the portrait of Walter Richter, born on Christmas Eve 1907 in Berlin-Lichterfelde-Ost, once an affluent suburb, though it seems that, the son of a bricklayer, Richter did not come from money. He was a “Hausdiener,” a domestic servant, spending his days seeing to the needs of others. After hours, he could finally be himself—and for Richter, being himself meant becoming somebody else. For Walter Richter liked wearing women’s clothes, a habit that quickly earned him the attention of the police and landed him on a register for homosexuals. “Attracts attention because of his powdered face and jewelry,” read an arrest report from 1940.

Richter’s extraordinary portrait (above) was taken earlier that year. He is sitting in his kitchen, next to a cupboard and in front of a closed curtain, on a stool that, from the little we can see, looks as uncomfortable as the one my grandmother, too, had in her kitchen. To Richter’s left are a sink and a small countertop, with a plate sitting on a drying rack and a crumpled dish towel. No matter how unpromising the background, this becomes Richter’s personal stage. He is striking a pose, his head tilted to the left, even as the rest of his body leans to the right. Richter’s right hand holds something, maybe a cookie or a biscuit, while his left grasps his dress, closing it more tightly around his body. Maybe this is not even a dress, but a piece of flowery fabric, made of the same floral material as his head kerchief, which he has fastened to his hair with what looks like a clip. His face is memorable, beautiful, the left half still in the shadow, while the right half is in the light, as if illuminated from within, the strong line from his nose to his mouth, emphasizing the light, provocative smile that plays around his closed lips.

We know that a female neighbor regularly supplied Richter with clothing and props, and that he was usually surrounded by his friends when he dressed up. Among the men who met, for fun and role-play in Richter’s apartments, first in Berlin-Steglitz and then in Lichterfelde, were a clerk, an apprentice locksmith, a railway worker, and a barber. One of these must have taken the photograph, and it was perhaps for him that Richter inscribed it in the back with “Zur Erinnerung an ‘Anna das Weib’” (in commemoration of “Anna the Woman”)? While the quotes he put around “Anna das Weib” appear to suggest that this was indeed a role Richter liked to play, on more than just this occasion, his choice of words, especially the emphatic “Weib” (woman with a capital W) also indicates that, for him, “Anna” was more than just a role. Likely, Richter’s female self, the product of careful work and preparation, might have had more reality, might have taken up more space in his mind, than that other, official part of his identity that showed up for work every day.

Today this photograph indeed commemorates Anna, though perhaps differently than Richter had imagined. There is no way he didn’t know what danger he was in, even before he was arrested. After the comparative freedom allowed non-gender-conforming people during the Weimar Republic, the Nazis wasted no time in clarifying their own views. On May 6, 1933, stormtroopers raided the Institute for Sexual Science directed by the legendary Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld, known for having coined the term “transvestite” in 1910. Proud, smart, and gay himself, the bushy-mustachioed Hirschfeld had long been a target of the right. But not only Dr. Hirschfeld’s books and patient records vanished during that raid. Gone, too, was Dr. Hirschfeld’s maid “Dorchen” Richter (no relation to Walter), the first known trans woman to have received a vaginoplasty; we will never know if she was killed that day or if she died later in custody. And that was only the beginning: between 1935 and 1945, around 100,000 men were arrested under Paragraph 175, which the Nazis rewrote so that it covered all sorts of “lewd” offenses, not just homosexual intercourse.

The Nazis caught up with Walter Richter in October 1940, apparently after someone had reported him to the Gestapo. He appeared before a judge on November 9. The charge: “widernatürliche Unzucht” (unnatural sexual acts). Richter was released, after nineteen long months in prison, on June 21, 1942. But the police didn’t allow him to go home: they had him transferred to Sachsenhausen instead. Here, the bricklayer’s son found himself once again surrounded by bricks. He toiled in a satellite camp of Sachsenhausen, the “Klinkerwerk” (brickworks), the largest such facility in the world, and certainly the most brutal, intended to be the source of the materials the Nazis needed for their grandiose architectural projects. At the end of each day, the inmates returned from there hauling a cart filled with corpses. Richter lasted little more than a month. He died on July 28, 1942, not quite thirty-five years old.

I don’t want to suggest that “Anna das Weib” marks Richter’s posthumous victory-over-adversity, that, because he left us that smiling, self-assured photograph, he had the last laugh. Yet what “Anna das Weib” shows—what it certainly showed me on that gray, damp day in Oranienburg a few months ago–is that Richter not only stood out in his own time but that he still stands out today and that, at least in my mind, he always will. At a time when millions donned a uniform to march in lockstep with a psychopathic dictator’s wishes and the orders of his disciples, Walter Richter went the other way, designing his own outfits, playing his own roles, guided by nothing but his own imagination. Richter wasn’t an artist. He didn’t put on his dresses for art’s sake, but for his own sake, and for the edification of his friends. Yet precisely because of that he was an artist after all, an artist with an audience, an artist “not in uniform,” to riff on the title of a 1934 book by Max Eastman. Walter aka “Anna” was the antithesis of uniformed drabness, the life-affirming opposite of what Arendt called the “thought-defying” boredom of totalitarian politics and its lethal effort to stamp out, in Governor DeSantis’ Florida and elsewhere, all that is beautiful, provocative, and different.