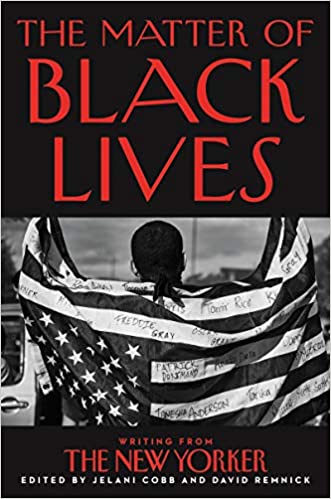

In the last 12 months, Professor Jelani Cobb, a staff writer for the New Yorker, has authored three groundbreaking books on race in America. The Matter of Black Lives: Writing from The New Yorker, which he co-authored with David Remnick, came out this fall. It collects many of the most thoughtful writers portraying Black life in America over the last century.

This past summer, he co-edited with Matthew Guariglia, The Essential Kerner Commission Report, which examined and explained the underlying conditions that led to a dozen urban uprisings between 1964 and 1967. Cobb says Republicans used the uprisings as political fodder but ignored the Report’s findings.

Last fall, he wrote The Substance of Hope: Barack Obama and the Paradox of Progress, where he explores the paradoxes that President Barack Obama’s election raised with regards to race and patriotism, identity and citizenship, and progress and legacy.

Licata: In The Matter of Black Lives, you imply that some people consider race a biological trait rather than a social artifact. A Northwestern University study found that 37 percent of white people and 25 percent of black people believe biology determines race. However, the Human Genome Project found that all humans are 99.9 percent genetically identical. Should thinking of race as a societal label instead of a biological fact be a significant discussion today?

Cobb: Yes, it’s important to have that discussion because race is a social concept based on political expediency and bad science and has wreaked havoc for centuries. And not just for black people but lots of others as well. The word race is so loaded with various meanings that you are never certain if the person who is saying and the person hearing are operating from the same definition.

Licata: You note that the inequalities between Black and white Americans are well documented by looking at morbidity and infant mortality and wealth and employment. Conservative whites have introduced legislation in over two dozen states to stop discussing race relations in public schools, saying that white students’ self-esteem would suffer from “white guilt.” How do we discuss race and black history in schools?

Cobb: It’s a difficult task because the laws are not written in good faith to establish an honest discussion. Without a truthful conversation of our history, the fault lines of the past will continue to haunt us. And I don’t think that “white guilt” need be  the product of an honest reckoning with our history. Instead, we need more enlightenment on how we can avoid repeating the problems of the past.

the product of an honest reckoning with our history. Instead, we need more enlightenment on how we can avoid repeating the problems of the past.

Licata: You wrote that Barack Obama in 2008 authored the term mixed-race as a replacement for mulatto to describe folks with multi-racial parents. Two years later, a Pew showed that more whites saw the President as biracial instead of Black, while most African Americans saw Obama as Black, not as mixed race. Did Barack Obama’s approach reduce discrimination?

Cobb: Obama was working with different definitions of race. Being an astute observer of society, he used mixed-race to have white people identify with his heritage. His white mother and grandparents looked like their grandparents. He obtained a greater surface area by white people identifying with him while Blacks still considered him Black. His approach helped us see race differently but still didn’t stop our grappling with defining race.

Licata: There are more than thirty Black Lives Matter chapters, and while there is a written statement of principles, no national organization is leading the chapters. Can BLM continue to be effective remaining as a movement without national structural leadership?

Cobb: I cannot prognosticate on that, but BLM has managed to be effective for a startling amount of time without one central leader. They have moved away from wanting a single charismatic leader, whose fortunes parallel that of a movement like the civil rights movement was with Martin Luther King. I think that’s a strength, but it can also be a liability.

Licata: You write that Reverend William Barber of North Carolina is a person most capable of crafting a broad-based political counterpoint to the divisiveness of Trumpism. What do you mean?

Cobb: Barber cogently looks at the world using facts and remains optimistic about changing it for the better. He organizes around having different kinds of people recognize that they live in similar economic conditions. His strategy is like MLK’s effort creating the Poor People’s Campaign. There is hope that an economic populism can cut across the lines that have divided people. Aside from economics, another potentially powerful bridge between conflicting movements is through a Christian-inspired movement, much like MLK did. Our democracy right now is at peril. We need to bring people together to do something about it, rather than lamenting.

Licata: BLM’s goal is “organizing people who are at the bottom,” like transgender people. The Human Rights Campaign reported that between 2013 and 2015 of the fifty-three known murders of transgender people, thirty-nine were African American. Has BLM’s inclusive approach weakened its message?

Cobb: I don’t think it has weakened BLM at all. Those statistics point out the real need to address the safety of those at the bottom. BLM is committed to organizing all these people regardless of who they are. People who have been exploited and marginalized are at the bottom in significant part because of their identity. BLM is providing a real need for an organization to put together an agenda for people at the bottom.

Licata: What are your thoughts on challenging progressive or liberal politicians rather than going after reactionaries or conservatives?

Cobb: I don’t understand that approach. The important thing is to deal with the people who are dragging the people of this country back decades.

Licata: In The Essential Kerner Report, you said that the report believed the absence of true liberalism had resulted in the riots. Can liberalism provide any long-lasting solutions to dismantling systematic institutional racism?

Cobb: Some aspects of liberalism address these solutions, but there are some deep structural troubles remaining. We must be prepared to deal with them, but we are often caught up in a type of tribalism in which we think this, but the other side thinks that. I’m most interested in useful ideas; I don’t care where they come from.

A shorter version of this interview appeared in the Seattle Times.