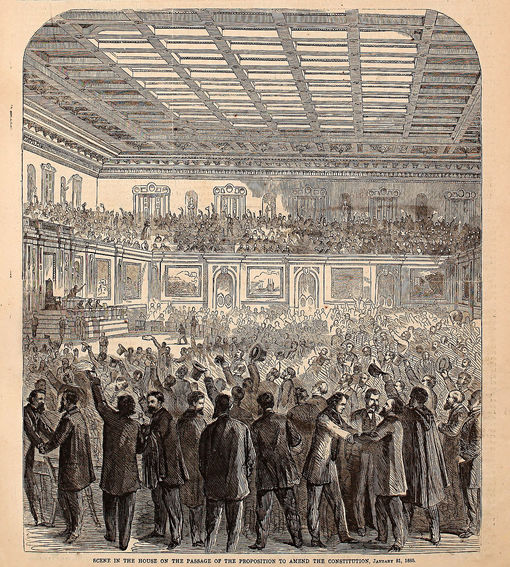

Image: Celebration erupts after the amendment is passed by the House of Representatives – Public Domain

The Thirteenth Amendment to the US Constitution reads “Neither slavery nor involuntary servitude, except as a punishment for crime whereof the party shall have been duly convicted, shall exist within the United States or any place subject to their jurisdiction.”

Slavery remains a punishment for crime; imprisonment is a continuation of slavery. That is the clause which in the view of Ava DuVernay and her many collaborators was weaponized to become a powerful legitimating tool of the segregation of the old Jim Crow, the convict leasing system, the new Jim Crow, and mass incarceration. Her film is therefore called “13th.”

The story of criminalization, the film suggests, began after the Emancipation Proclamation. However, the story helps us see the similar process in the formation of working-class, and the divisions within it, elsewhere.

The English working class as a self-conscious historical force is said to have had its origin with the London Corresponding Society of 1792. The first page of The Making of the English Working Class proudly enunciated in its title the democratic principle of the L.C.S., “Members Unlimited.” But the membership was limited because we read on the same page that members were required to agree “that the welfare of these kingdoms require that every adult person, in possession of his reason, and not incapacitated by crimes, should have a vote for a Member of Parliament.” Prisoners were thus excluded.

That’s why years ago, inspired by Malcolm X, many of us scholars studied crime and began to make the acquaintance of folks in prison. We learned that the story of capitalism and democracy began earlier. Criminalization was necessary to both. It is coeval with capitalism. It is parallel to capitalism. It is conterminous with the commodity form. In fact, criminalization belongs to the essence of capitalism.

The U.S. Constitution begins with a phrase borrowed from the Levellers, “We the people.” The Levellers during the English Revolution of the 1640s had also apparently advocated universal suffrage, or real democracy. Yet on closer examination this first democratic political party had qualified this grand ideal in ways similar to the L.C.S. or the 13th Amendment. The Levellers’ petition of January 1648 excluded from the franchise those who “are not, or shall not be legally disfranchised for some criminal cause, or are not under 21 years of age, or servants, or beggars.” Beggars didn’t work and servants had masters. Women, too, were silently excluded. The Levellers put emphasis on the “free-born Englishman” and for the next two or three centuries the figure of “the free-born Englishman” reigned supreme in the popular imaginary. But delinquency or criminality forfeited that birthright. Criminalizing was a weapon of state to deny people the vote.

My point is that criminalization has been a weapon against workers from day one. As a little litigious clause in a great amendment, or as a sly afterthought in Leveller petitions, or even as a limitation to “Members Unlimited” this kind of qualification to the meanings of freedom has been a nasty worm in the apple. Democracy was not for delinquents, the vote was not for those convicted in court. Freedom was not for all; slavery persisted. The state project of criminalization rots the orchard.

What the 13th Amendment did was consistent with more than two hundred years of working-class history. Slavery, servitude, and the poor are parts of, or aspects to, the class that is forced to work not for subsistence but profit, producing wealth for others. Watch the documentary film, the “13th” because it is a fundamental introduction to criminalization. Having done that, then we may with Eugene Debs ponder this thought, “While there is a soul in prison I am not free.”

Finally, we cannot shirk from the questions, what is crime? who are the real criminals? Freedom begins with our answers.