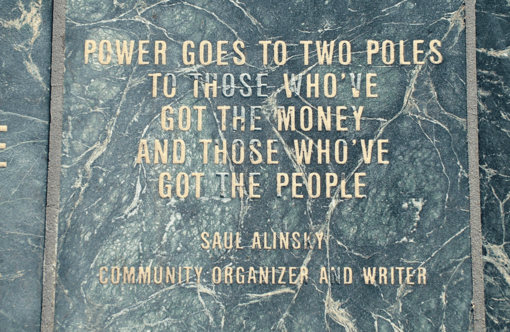

Photo by Pat (Cletch) Williams | CC BY 2.0

Called shareholder activism and capital stewardship, the recent past has seen more actions taken by shareholders in shaping U.S. culture. One skilled proponent of proxy power in the 1960s and 1970s was Saul Alinsky. His actions and writings have much to offer today.

Saul Alinsky

Saul Alinsky was a proponent of mass-based community organizing and its development as a way for people to build power in the United States. He anticipated and developed a space for it in post-World War II U.S. that used democratic rhetoric juxtaposed against Nazi totalitarianism and Cold War conflict with the Soviet Union. He was shaped by his friendship with United Mine Workers of America President John L. Lewis and first attracted national attention for his success in building the Chicago Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council. Alinsky described himself as a professional anti-fascist.

Alinsky followed varied interests in his career from criminology to social work and then community organizing. Before his death in 1972 he declared that organizing the middle class through “Proxies for People” would be “the culmination of my career”.[1]

Proxies for People

Alinsky analyzed that power flowed between organized money and organized people. His first book, Reveille for Radicals, published in 1946, was an appeal to liberals that included an extended explanation that U.S. labor unions were symbiotically tied to capitalism. Although critical of labor unions in some ways and seeking to redefine radicalism, he positively cited the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America’s use of its Amalgamated Bank to lend money to forestall a plant closing and convince other banks to delay on foreclosing.[2]

Twenty years of action and reflection led to his campaign in Rochester, NY. His Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF) got a three-year contract with churches in Rochester, New York to organize. The significance was to form an organization in a Northern city that could model an approach in seeking civil rights for African Americans and economic justice for low-income and unemployed people.

The church-based organization, called FIGHT, had a goal of getting unemployed black people hired by local governments and companies. In September 1966 it targeted Eastman Kodak, a manufacturer of cameras and film. By December it had an agreement to be the exclusive source for 600 black trainees but later that same month Kodak reneged on that agreement.

By March 1967 Alinsky and his circle of advisors developed the idea of expanding the fight by buying shares of Kodak stock and attending the April annual meeting. Soon this grew to seeking commitments nationwide from religious denominations owning Kodak stock to withholding votes and using the meeting as forum to denounce Kodak’s reneging on its commitment to FIGHT. FIGHT’s campaign leading to and including Kodak’s annual meeting resulted in Kodak management restating its position that it would not honor the agreement. The tension built at the meeting was sustained over several months and led to an understanding of a vaguer agreement between FIGHT and Kodak in June 1967.[3]

Alinsky applied the proxy tactics again in Chicago in 1970. Citizens Action Program (CAP) was formed around environmental issues in response to air quality problems. Targeting the high-sulfur coal burned by Commonwealth Edison, CAP organized and mobilized stock proxies and conducted an action at its annual meeting in April 1970. This led to Commonwealth Edison agreeing to use low-sulfur coal.[4]

Alinsky developed stock proxy strategies into a concept of how to reach middle- and upper middle- class people he called “Proxies for People”. By the time he published Rules for Radicals in 1971 he devoted a whole chapter to speculating on its potential as a tactic. He used his experience with proxies to illustrate the principle that tactics were further developed through action. He recounted its development in Rochester. He described how his vision of its potential kept expanding. As he sought to have allies sign over their proxies, he was stunned by shareholders who mildly pushed back at his request. Instead of signing over the proxies, they asked to retain the proxies and deliver FIGHT’s message to Eastman Kodak themselves. He was greatly encouraged by their reaction.

Potential and problems

He said that he would probably leave IAF to aid the formation of “Proxies for People”, viewing it as fundamentally different in ways that could not or should not be folded into IAF.[5] He invited Hillary Rodham Clinton, who had interviewed him in 1969 for an undergraduate thesis, to head the effort (she declined).[6] This targeting of Clinton for the effort is an example of how the description of “Proxies for People” fit with the intended audience for Rules for Radicals of disaffected young people. He viewed college students with their training in research and analysis as having an important role to play in the further refinement of the use of company stock in making demands of companies. Instead of being alienated from U.S. society, he hoped that young people could unite with their parents in changing it.

Alinsky’s excitement was palpable in the interviews he gave at the time. He wanted to build a national organization as a clearinghouse for proxies, in a way that respected individual privacy, but still moved proxies from owners to people who could attend the meetings. In a nutshell, he wanted an organization to sponsor resolutions, get mass numbers of people into shareholder meetings, and shine a spotlight on the companies even as resolutions were defeated. He also thought that companies’ competition with each other could be harnessed to get them to pressure each other. [7]

He was keenly aware of the limitations of “Proxies for People”, saying that the middle class would be “suspicious, even hostile at first” and that there were a “great many negatives to this approach”.[8] He anticipated that companies would warn shareholders that resolutions would decrease investor dividends. He acknowledged the power of this argument but thought that people would be so energized by working together that it would overcome that. He also foresaw – and regretted — that “Proxies for People” would rely on individuals and that institutions such as churches, foundations, and universities would be opposed. He saw in the Kodak campaign that churches were lost to the cause when their corporate laypeople opposed it. He anticipated the same from the foundations he had so assiduously and successfully cultivated over decades and also universities. He consoled himself with universities’ opposition with the thought that it would drive more students his way.[9] In the context of differences among institutions and individuals on voting proxies, he was hopeful that action would lead to dynamic “shifts and changes”.[10]

Today the same disconnect occurs between money managers and people who have deferred wages into pensions and retirement accounts. There is the same hesitance to trade immediate dividends for an uncertain greater good in the future. Institutions such as foundations still resist doing as much good with their investment portfolios as with grants made from the proceeds of their investments. Alinsky’s call to focus on action, by ourselves and others, and an openness to be changed by it is still relevant.

Dan Willett is a researcher for the Capital Strategies Department, International Brotherhood of Teamsters.

[1] Eric Norden, “Empowering people, not elites; interview with Saul Alinsky”, Playboy, March 1972

[2] Saul D. Alinsky, Reveille for radicals, (University of Chicago Press, 1946), in passim, pages 35-50; Amalgamated Bank and Kahn Tailoring Company, pages 46-47

[3] Sanford D. Horwitt, Let them call me rebel; Saul Alinsky, his life and legacy, (Alfred A. Knopf, 1989),pages 495-505

[4] Aaron Schutz, Mike Miller (editors), People power; the community organizing tradition of Saul Alinsky, (Vanderbilt University Press, 2015), page 202

[5] Saul D. Alinsky, Rules for radicals; a pragmatic primer for realistic radicals, (Random House, 1971), pages 165-183

[6] Schutz, Miller, op cit, pages 196-197

[7] No Listed Author (1971) “Proxies for People: A Vehicle for Involvement”, Yale Review of Law and Social Action: Vol. 1: Iss.4, Article 6, pages 65-66, http://digitalcommons.law.yale.edu/yrlsa/vol1/iss4/6

[8] Norden, op cit; “Proxies for People: A Vehicle for Involvement”, op cit, page 69

[9] “Proxies for People: A Vehicle for Involvement”, op cit, pages 66-67

[10] Ibid, page 69