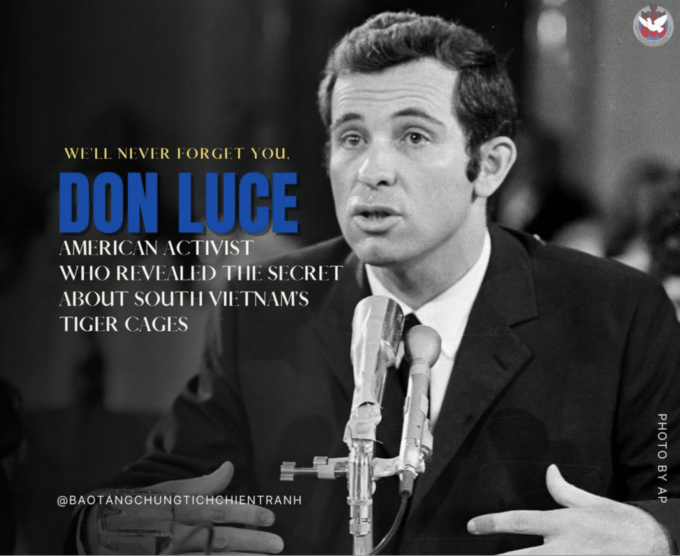

Don Luce, who passed away on November 17, 2022, a week before the US Thanksgiving, at the age of 88 in Niagara Falls, NY, was a kindred spirit and one of my heroes on a decidedly short list.

While I am a suburban boy from Wilmington, Delaware and Don a farm boy from Vermont, he was in Vietnam during a time of war and I am here during a time of peace and relative prosperity, separated by a generation, I feel a connection to him engendered by our mutual love of and respect for Vietnam, our commitment to justice, and our penchant for speaking truth to power when need be.

In death as in life, Don is an inspiration to me and countless others. Evidence of the global outpouring of grief, condolences, and memories from so many in the US, Vietnam, and elsewhere who knew, or knew of, him. Below are edited versions of a few of them. Many were written for Dr. Mark Bonacci, Don’s husband and companion of 43 years.

My heartfelt condolences to the family and especially to Mark. Don’s contributions to Americans’ understanding of what was really happening in Vietnam shall always be appreciated and remembered. The ultimate compliment he received was from Ambassador Martin who blamed Don and IVS for the U.S. “losing the war .” Alas, no credit to the Vietnamese. Thank you, Don, for ‘speaking truth to power’ and for dedicating your life to making the world a better place. -Tom Miller, Berkeley, CA

Don was a loving man with great heart and humanity. He was generous with his local and international projects. He cared for the most vulnerable among us and was not shy about convincing those with power and resources to work with him. -Katherine Johnson and Victor Marwin, Buffalo, NY

Don was a beloved friend and colleague during my time in Vietnam. His deep love, knowledge, and singular fluency in Vietnamese enabled him to tell the truth of that war to Congress and the American public, helping to end it. What a great soul and we miss him. – Judy Danielson, Denver, CO

Don Luce was lauded for his achievements in obituaries published by well-known mainstream media outlets such as The New York Times (NYT) and The Washington Post. In a Tweet, John Stauber exclaimed “#RIP #DonLuce! When I was a kid, he was one of my heroes. Don’t you wish you could die with an obit headline like this?” in reference to the NYT obituary by Seth Mydans: Don Luce, Activist Who Helped End the Vietnam war, Dies at 88. The story of his passing was also picked up by various regional and local newspapers, including in his home state of Vermont.

Don’s death in Niagara Falls was keenly felt halfway around the world in Vietnam, where I have lived since 2005, especially by the prison camp survivors whose fate he and Tom Harkin helped bring to the attention of the world. It was country to which Don felt a special bond and continued to visit on a regular basis, including reunions with the former prisoners of the US and the Republic of Vietnam (South Vietnam).

From Idealistic Volunteer to Anti-War Activist

Perhaps the most comprehensive and illuminating article about Don Luce and his life of good works in Vietnam and the US is a From Tiger Cages to Soup Kitchens (2015) by Ted Lieverman. He writes, “As a young man, Don Luce crossed paths with history in Vietnam, evolving from a gung-ho U.S. aid worker into a persuasive opponent of the war, famously exposing the use of ‘tiger cages’ to hold political prisoners, but his life took other remarkable turns.”

The son of a dairy farmer and a teacher, Don Luce hailed from an old New England family. He went to Vietnam in 1958 as a self-proclaimed apolitical Eisenhower conservative. A recent Cornell University graduate with a Master’s in agricultural development to supplement his undergraduate degree in farm management from the University of Vermont (1956), Don was on his way to South Vietnam to work as a volunteer for International Voluntary Services (IVS), a US government-supported nonprofit that placed volunteers in humanitarian and development projects around the world and was the model for the US Peace Corps.

A Vermont newspaper retrospective on Don’s life, Remembering Don Luce revealed that it was Don’s friendship with Malay students at Cornell that sparked his interest in Asia. His initial assignment was to run an experimental agricultural station to help rural Vietnamese grow a better variety of sweet potato. Within three years, he was promoted to IVS country director for Vietnam.

As the war heated up and military advisers were followed by troops, Don witnessed and experienced first-hand the destruction of villages and the murder of innocents, which ultimately led to his widely publicized resignation from IVS.

IVS Resignation

On September 19, 1967, almost a decade after Don arrived in Vietnam, he and three other staff leaders resigned. Below is an open letter to President Johnson signed by nearly 50 IVS staff, a story that landed on the front page of the NYT:

Dear Mr. President:

As volunteers with International Voluntary Service, working in agriculture, education, and community development, we have the unique opportunity of living closely with Vietnamese over extended periods of time. Thus, we have been able to watch and share their suffering, one of us as early as 1958. What we have seen and heard of the effects of the war in Vietnam compels us to make this statement. The problems which the Vietnamese face are too little understood, and their voices have been too long muffled. It is not enough to rely on statistics to describe their daily concerns.

We present this statement not as spokesmen for International Voluntary Service, but as individuals.

We are finding it increasingly difficult to pursue quietly our main objective: helping the people of Vietnam. In assisting one family or one individual to make a better living or get a better education it has become evident that our small successes only blind us to how little or negative the effect is, in the face of present realities in Vietnam. Thus, to stay in Vietnam and remain silent is to fail to respond to the first need of the Vietnamese people – peace.

While working in Vietnam we have gained a genuine respect for the Vietnamese. They are strong. They are hard working. They endure. And they have proved over and over their ability to deal with foreign interference. But they suffer in the process, a suffering greatly intensified by today’s American presence. This suffering will continue and increase until Americans act to ease their suffering. It is to you, Mr. President, that we address ourselves.

In a chapter of his prophetically titled 1968 book Vietnam Will Win! the legendary Australian journalist Wilfred Burchett (1911-1983) referenced a telling excerpt from their resignation letter:

Perhaps if you accept this war, all can be justified – the free strike zones, the refugees, the spraying of herbicides on crops, the napalm… We have flown at a safe height over the deserted villages, the sterile valleys, the forests with huge swathes out and the long-abandoned rice-fields… We read with anguish the daily count of ‘enemy’ dead. We know that these ‘enemy’ are not all combat soldiers committed to one side. Many are old men, women and young boys who ran when a helicopter hovered, who were hiding from bombs in an enemy bunker, or who refused to leave their farms…

Burchett added that

another 35 IVS members, almost all the Americans, also wanted to sign but were intimidated by U.S. Embassy threats to draft them immediately into the U.S. Army if they signed. Apart from a few isolated Quaker groups, the IVS was the only American organization to have real contacts with the population in the countryside. Some of the signatories of the ‘open letter’ told me that virtually all members had come to South Vietnam deeply convinced of the righteous nature of the American commitment in Vietnam but had become sickened by the realities. The signatories demanded, among other things, an end to the bombings of North Vietnam, recognition of the NLF, an immediate end to the practice of defoliation (the spraying of crops with toxic chemicals) and an end to the war.

In an informative 2012 blog post Stuck in the Middle: International Voluntary Services and the Humanitarian Experience in Vietnam, 1957 – 1971, Douglas Bell offered a precise description of IVS and similar organizations: “Located between the Vietnamese people and the American government, humanitarian organizations demonstrate the experience of American civilians in Vietnam and reveal that they wanted passionately to help the people of South Vietnam, but became an important voice in criticism of U.S. policy.”

Vietnam: The Unheard Voices

Our enemy is not a man;

If we kill the man, with whom do we live? …

Our enemy is inside each one of us.

–Pham Duy (1921-2013), Vietnamese folk singer

After leaving IVS, Don worked for a year as a research associate at the Center for International Studies at his graduate alma mater during which he wrote Vietnam: The Unheard Voices with John Sommer, a former IVS colleague. It was published in 1969 by Cornell University Press after Don had already returned to Vietnam.

In the foreword to Vietnam: The Unheard Voices, which is available from the Refugee Educators’ Network website in PDF format, Senator Edward M. Kennedy wrote in January 1969, “Don Luce and John Sommer are two extraordinary young men. They were not involved in the Viet Nam war as we know it, although they and their colleagues personally lived through this tragedy – and still do. They were not on the side of a great power or a nationalistic movement, although they, too, have fought for others – and still do. Luce and Sommer became a part of Viet Nam. But most importantly, they and a few others became a part of the people, listened to them, at a time when a thoughtless war was rolling over them.”

In the preface they described their path from idealism to the untenable situation that led to their resignations:

Our jobs in Viet Nam, we soon found out, were to increase sweet potato production and to assist in the opening of primary schools in the villages. Politics, in fact, seemed quite irrelevant, and the challenges and rewards of our work were such that we decided to stay well beyond the initial two years of our contracts. Because we were trained to speak Vietnamese and lived among the people of the country, we increasingly came to know and admire them. We ourselves became far more committed than we had ever anticipated.

Over the years, however, the sufferings of the Vietnamese increased as warfare returned to the country. As the range of our own experiences also broadened, we began to see unnecessary mistakes being made by our American government in response to the new conditions. Our early humanitarian motives for wishing to serve in Viet Nam were being thwarted. …It became inevitable that our commitment to Viet Nam would take on political overtones. Finally, as we saw too many opportunities for reforms being passed by, and as the situation became increasingly desperate, we realized that we as individuals could no longer continue in our same roles in South Viet Nam.

In Viet Nam, our job, in a sense, was to bridge the gap between the makers of policy and the people affected. But the voices of the Vietnamese people – and our own as well – we not often heard. Now we raise them again, in hopes that those who have erred can learn from past mistakes, and that those who have suffered and given of their lives will not have done so entirely in vain. The Vietnamese people have much to teach all of us.

Fittingly, Don Luce and John Sommer conclude their 336-page book with this thought, which combines empathy and compassion and urges the reader to view the world from the perspective of a global citizen:

…we must begin with a more humble understanding of this world and of the aspirations of its diverse peoples. We must hear their voices and try to put ourselves in their position. Only when we make this effort can we begin to respond honestly and effectively and learn some of the lessons of Viet Nam. For in the final analysis, the lesson of Viet Nam is that ‘our enemy is not a man; if we kill the man, with whom do we live? Our enemy is inside each one of us.’

It is sage advice that fell on deaf official ears then, as now.

As both discovered, those who embraced this powerful, Buddhist-like message did not endear themselves to either side in a time everyone was pressured to choose in a binary world. Don later said, “We were trying to find a way to give the Vietnamese a voice in the debate.”

This book and Don’s years of experience in Vietnam formed the basis for the Indochina Mobile Education Project, affiliated with the Indochina Resource Center, in which he later toured the US in a minivan giving talks about the impact of the war on Vietnamese civilians. One indication of Don’s evolving mindset was a talk he gave in December 1967 at the University of Montana-Missoula titled “The Conversion of a Hawk.”

Scudder Parker, a fellow Vermonter who worked with Don as part of Clergy and Laity Concerned, recalled that “Don Luce’s opposition to the Vietnam war grew out of his knowledge of and love for the people of Vietnam. … His way of protesting was to bring a stunning display of almost life-sized panels showing the people he knew at work, at play, at rest. He shared their poetry, history, music and stories.”

He brought the war home so that it was no longer all about the US and statistics as a metric for “progress” but, more importantly, about the suffering of the Vietnamese people Don and his colleagues worked with, cared about and, in many cases, called friends. He was the quintessential people-to-people ambassador, an enlightened link between the two countries.

The Tiger Cages

Côn Sơn Island is a place I have visited several times and wrote about in a 2021 essay Of Spirits, Martyrs & Legends: the Magic & Sorrow of Vietnam’s Côn Sơn Island. It is beautiful yet haunting:

A short up-and-down overwater flight from Tân Sơn Nhất International Airport and, voilà, you’ve arrived. While your destination is just off the coast of southern Vietnam, it may as well be another world. In less than an hour, you are transported from the hustle and bustle of Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon) to the quiet and melancholic beauty of Côn SơnIsland, the largest and most infamous in the 16-island Côn Đảo Archipelago.

Vietnamese come from far and wide not just to enjoy breathtaking views of the sea, fresh seafood, and invigorating walks along pristine beaches, but also to participate in a solemn pilgrimage to dark places that are a legacy of French and US brutality. They are a stark testament to the supreme arrogance of one fading colonial power that handed the blood-stained baton to an ascending neocolonial power, both convinced they had the right to determine the destiny of a country not their own. Many of those who travel here are war veterans and former prisoners who pay homage to their fallen comrades.

It is here where Don and then congressional aide Tom Harkin veered off the prescribed path with Augustus Hawkins and William Anderson, congressmen from California and Tennessee, and found the tiger cages using a map drawn by a former prisoner who had been one of Don’s students in Saigon.

Harkin was subsequently fired for not handing over the film of the shocking images he took, which later appeared in a July 1970 Life magazine article. Don had his mail privileges revoked by the US Embassy in Saigon, was put under surveillance by the police and, finally, expelled from the country less than a year later.

The surveillance included one unsuccessful attempt on his life. In this colorful yet ominous story with a Keystone Cops touch, Don returned to his Saigon apartment one day to discover that it had been broken into. The operatives tied a poisonous snake in his bed sheets hoping he would crawl into bed that night and they would accomplish their mission. The only problem is that Don never made his bed, a glaring oversight that blew their cover.

One of my favorite references to Don appeared in a November 1970 Time essay The Press: Expelling the Exposer about his expulsion as retribution for the tiger cages exposé: “Don Luce is to the South Vietnamese government what Ralph Nader is to General Motors,” a well-deserved compliment and a rhetorical badge of honor.

In a parting shot before he boarded his flight to the US in early May 1971, Don wrote a letter that was published by numerous newspapers in the US about an 18-year-old student arrested by South Vietnamese police on suspicion of aiding the North. His legs grew numb from being shackled for long periods of time and he was dying of tuberculosis. Don wrote, “I am writing this letter to say that you and I are responsible for this man. Our taxes are paying an ever-growing police force to intensify its repression.”

In his essay The Tiger Cages of Viet Nam, Don began on an intensely personal note that sums of the experience of many young Vietnamese of the day:

My best friend was tortured to death in 1970. Nguyen Ngoc Phuong was a gentle person. But he hated the war and the destruction of his country. He was arrested by the U.S.- sponsored Saigon police in one of his many anti-government demonstrations. After three days of continuous interrogation and torture, he died. ‘He was tortured by the (Saigon) police, but Americans stood by and offered suggestions,’ said one of the men who was in prison with him.

Don compared that torture and murder, multiplied by thousands of times, to the Abu Ghraib torture and prisoner abuse, noting that the main difference was the US taught and financed the Saigon police and the US military carried out the torture themselves in Iraq. He wrote,

There were, however, many Vietnamese who were tortured by Americans before being turned over to their Saigon allies and put into jail. Reports of suspected Viet Cong being thrown out of helicopters, peasant farm people tied to stakes in the hot sun, and young men led off to execution by U.S. soldiers are well-documented by U.S. soldiers and journalists.The U.S. paid the salaries of the torturers, taught them new methods, and turned suspects over to the police. The U.S. authorities were all aware of the torture.

In the same essay, Don told the tragic yet inspiring story of Thieu Thi Tao, whose soft and gentle voice I can still hear from a US television interview. Tao was one of 300 women imprisoned in the tiger cages. Before that, as Grace Paley wrote in her 1998 book Just As I Thought, she had been tortured while in custody in Saigon. This included being beaten on the head with truncheons, having her head locked between two steel bars, water forced down her throat, being suspended above the ground, and subjected to electric shock.

In 1969, Tao, then a student, was transferred to Côn Sơn Island, where her misery continued. A year later, she was sent to the Bien Hoa Insane Asylum where she was hung from an iron hook. She still wears a neck brace because of the damage to her spine. The reason for her arrest? She refused to salute the South Vietnamese flag.

She later wrote about the Congressional delegation’s 1970 visit to Côn Sơn Island:

You saved our lives. I still remember the strange foreign voices when you came. In the cages, we wondered what new indignities were to be visited upon us. But a foreigner [myself] who spoke Vietnamese with a heavy accent told us it was a U.S. congressional investigation. We had prayed for such an inquiry and took the chance to speak of the tortures. We begged for water and food. We were dying you know.

(Don read this aloud in a 2015 YouTube interview with Drew Pearson.)

Taking Anti-War Protests to the Next Level

While the anti-war protests were in full swing, news about the tiger cases sparked global outrage and threw gasoline on an already raging fire. Protesters began to make references to the tiger cages and used them in street theater outside the US Mission to the United Nations in midtown Manhattan and elsewhere. In Boston, activists locked themselves inside mock tiger cases for a week of daily vigils and in London they invited people to enter a cage and to see what that confinement was like even if only for a few minutes.

It is why Graham Martin, the last US ambassador to South Vietnam, in testimony before the US Congress in 1976, singled out Luce as one of the main reasons the US lost the war. In a 2017 interview sarcastically entitled You Can’t Make This Up: The Man Who Lost Vietnam Bill Turpie asked Don what he thought of Martin’s comment.

He laughed and pointed out that we were so ill informed about the country and its people that we had no chance of succeeding. He added that we never had an Ambassador who could even say ‘hello’ in Vietnamese. He also noted that maybe if we had been smarter, more humble and, yes, honest we might have taken a different approach and not engaged in a war that cost the lives of 50,000 U.S. personnel, and caused more than a million civilian deaths.

(Note: At least 3.8 million Vietnamese were killed during the war, over half of whom were civilians.)

Post-War Life

After the war, Don moved to Washington, D.C., where he later served as the IVS director until 1997. In a 1978Washington Post interview about Don’s continued post-war activism, he reflected on his politicization, saying, “I went from growing potatoes to writing about tiger cages because my sweet potatoes got defoliated and I got angry. It’s almost that simple.” Perhaps more than any other quote or statement written about Don, that one sums up his process of quiet radicalization in which “radical” is defined as a change or action “relating to or affecting the fundamental nature of something; far-reaching or thorough.” At the time, Don was giving at least 1,200 speeches a year sharing his Vietnam-related knowledge and experience, and how is related to “new Vietnams” in Iran, the Philippines, and Thailand.

In a November 2019 presentation at Niagara University, Don shared a similar example, describing how he had worked on a small island with a group of farmers to grow “Sugar Baby” watermelons, a sustainable source of food that easily cross-pollinates. One day the US military defoliated that part of the island, killing all the plants. When Don protested to a US representative, explaining that the damage cost an estimated $10,000, the latter replied, “The whole goddamn country isn’t worth $10,000.” Within weeks, all of the farmers had joined the National Liberation Front (Viet Cong), a scenario that repeated itself with predictable regularity throughout South Vietnam.

After his second stint with IVS, Don taught in the sociology department of Niagara County Community College and then served as director of public relations and development for Community Missions of Niagara Frontier for two decades until his retirement in 2018 at the age of 84. Community Missions serves young people, adults, families, the homeless, individuals with psychiatric problems, people with HIV/AIDS, trafficked youth and adults, and parolees, in other words, those living on the margins of society.

The Measure of the Man

News of Don’s death filled me with both sadness at the loss and gratitude for the exemplary life he led. Thomas Fox, a former International Voluntary Services (IVS) colleague, described him this way: “His manner was always quiet, his humor sharp. He was a shy person, in that sense ill-equipped to play the prophet role he came to endure. Don had no rough edges. His strength – and it was enormous – came from his ability to fasten onto a truth and speak it plainly. He was always most passionate when he spoke on behalf of those who were never allowed that opportunity.”

In a quote used in several obituaries, Gloria Emerson (1929-2004), the NYT correspondent in Vietnam for three years, described Don as “a gentle and austere man, born without a temper, almost unable to return anger.” “His was a Vietnamese world, she wrote in her book Winners and Losers: Battles, Retreats, Gains, Losses, and Ruins from a Long War. “He did not hang out with American reporters or personnel and saved documents other reporters did not read.”

In a 1971 letter to the editor of The New York Review of Books, Holt Ruffin wrote about the South Vietnamese government’s refusal to renew Don Luce’s accreditation, stating that “To the American authorities in Saigon, Luce is both a great nuisance and a great mystery – the latter because he has a most un-American love for the Vietnamese people.” Time and again, Don chose the victims over the victimizers, the exploited over the exploiters.

Don Luce will forever be associated with the “tiger cages” of Côn Sơn Island but that was just one eventful chapter in a life filled with adventure, good deeds, and personal tragedy. One of Don’s cousins Tweeted that he was a “a profile in quiet courage,” adding that Ambassador Martin’s criticism of him as one of key reasons the US lost the war was “a fine legacy – but only a small part of the man.”

In a 2015 interview, Don, who had just turned 80, said, “now I try to concentrate on helping a few people have an easier life,” adding that he looks at life “from a Niagara Falls soup kitchen perspective,” in reference to the homeless and parolees he worked with.

“Living Proof of Evolution to a Higher State of Being”

A fun fact I shared with Don and Mark is that Don and I share a few strands of DNA; he’s a distant paternal cousin through both parents. On his mother’s side, our common ancestors are Phillip Wheeler (1698-1765) and Martha Salisbury (1698-1745). We’re also related through his paternal grandmother, Almina Celia Church (1866-1938), which means we’re both direct descendants of Mayflower passengers Stephen Hopkins and Richard Warren.

While we are both great-grandchildren of settler-colonizers whose actions spelled the beginning of the end for Native Americans who had lived in the Puritans’ New World for millennia, we learned about the dark side of our country’s history through knowledge and experience. As young men, we overcame a past characterized by exploitation and violence in what became the United States and well beyond its borders as manifest destiny went global and global domination become a cornerstone of US foreign policy.

I Am Not Here

My actions are my only true belongings.

I cannot escape the consequences of my actions.

My actions are the ground on which I stand.From the Buddha’s Five Remembrances (translated by Thích Nhất Hạnh)

I and many others find consolation and solace in the fact that while Don has left the physical world, his indomitable spirit and love for his fellow human beings live on. He would appreciate the Buddha’s Five Remembrances, of which the last one is about the importance of actions as our only true belongings. We enter the world with nothing and leave it the same way. What remains after we breathe our last?

The ground on which Don stood in Vietnam and his home country was rock solid, his legacy one of kindness, caring, and a quiet yet steely determination to seek justice for those fellow human beings who were victims of state-sponsored violence and viewed as expendable by an unjust and unfair society. He consistently walked the talk without regard to his personal safety.

The people Don touched and the lives he changed are his immortality and our inspiration. Thích Nhất Hạnh wrote in I Am Not Here, “I don’t see why we have to say, ‘I will die,’ because I can already see myself in you, in other people, and in future generations.” Although Don’s mortal remains rest in Forest Lawn Cemetery in Buffalo, New York, I see him in myself, in other people, and in future generations.

Postscript: This local obituary contains information about Don’s memorial service on December 26, 2022 at the Community Missions of Niagara Frontier in Niagara Falls, NY. Thanks to Mark Bonacci’s efforts, the service will be videotaped and posted on YouTube. As soon as it’s available, I will post this information on my blog An International Educator in Viet Nam.