As a result of the omicron variant of the coronavirus, many school districts across the country are finding themselves short of teachers, who are quitting, getting sick or even dying.

Some schools have even called on parents to step in to provide adult supervision in classrooms. In New Mexico, the governor has asked National Guard members to serve as substitute teachers.

Normally schools hire substitutes to cover teacher absences. But there are so many teachers out with COVID-19 that the demand is much higher than usual.

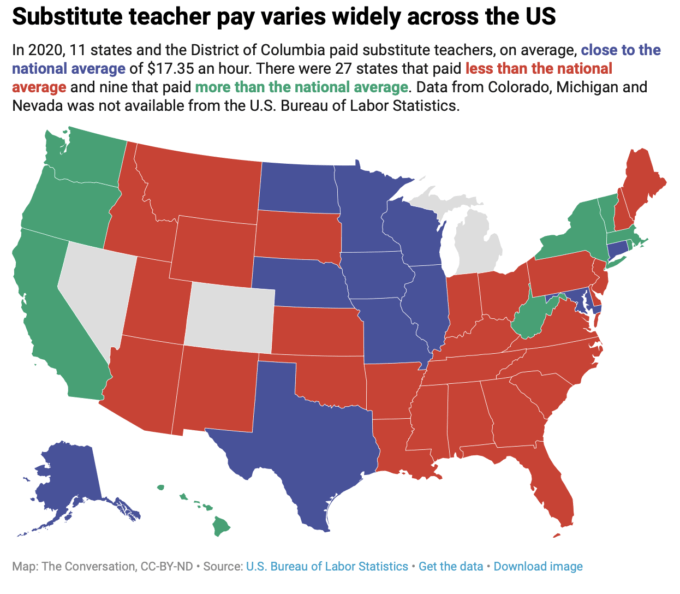

Pay for substitute teachers averaged $17 an hour in May 2020, according to federal figures. Assuming a substitute worked as much as possible – seven hours a day for 180 school days – that’s $21,420 a year, which is about one-third of the national average pay for full-time teachers. It is also below the poverty line for households with three people. Because school breaks are short, people who are regular subs may not be able to pursue longer-term work.

And that’s on the high end. Substitute teaching work is not always steady and doesn’t usually earn benefits, so it’s less attractive in a job market where workers have many options.

As education administrators and scholars of school leadership, we see school districts across the U.S. adjusting their requirements, and their compensation, for substitute teachers – all in an effort to keep schools open despite large numbers of staff out sick.

Why are there substitute teachers?

With the rise of compulsory education in the U.S. in the early 20th century, and the subsequent emergence of collective bargaining agreements for public school teachers, schools began needing to hire substitute teachers. Contracts often gave teachers a specific number of sick or personal days off. School districts had to provide coverage when a regular teacher was out, either for a short period of illness or a longer time, such as a maternity leave.

In general, states set minimum requirements for substitutes. In Alabama, Colorado, Georgia, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, Virginia and Wyoming, anyone with a high school diploma can be a sub, unless a specific school district has implemented a higher level of requirements. But most states require at least some college credits, and local school boards often set additional requirements, such as licensure in the subject where the person will work as a substitute teacher.

Subs are employed in a variety of ways, sometimes through collective bargaining agreements with school districts, including formal approval as employees with negotiated compensation and working conditions, or as independent contractors, or through external temporary staffing agencies. Their pay is typically determined by school districts. In general, short-term subs, who fill in for a teacher for a day or so at a time, are paid the least. Subs tend to get paid more if they work some number of days in a row, or if they are engaged to fill a longer-term absence. Pay also can increase depending on a sub’s educational level, license status or prior teaching experience.

Though the national average in 2020 – the most recent year for which data is available – was $17 an hour, actual pay varies widely by location. Districts in and around southeastern Maryland paid an average of $42.13 an hour in 2020. But school districts on Alabama’s Gulf Coast paid $8.35 an hour on average that same year.

What can be done to address the shortage?

The standard approach to a worker shortage is to raise pay and other compensation. One school district outside San Antonio, Texas, has temporarily raised its substitute teacher pay by as much as 20%, to between $98 and $150 per day, depending on a person’s qualifications.

In education, however, we have more often seen a reduction in required qualifications for a particular job, demanding a lower-level license or less prior experience. That’s happening, too, such as in Kansas, which temporarily eliminated the statewide requirement that subs have at least some college-level education.

However, our experience as school district leaders has shown us that attracting and keeping substitute teachers requires more than fair compensation.

Often, substitute teachers are viewed on the school system’s periphery rather than as an integral core. For instance, subs often are not included in district events such as professional learning opportunities or districtwide communications. Research has demonstrated that even though substitutes are necessary for the continuing function of schools, substitutes do not see the organization as valuing their contribution.

Some substitutes, such as retired teachers, may prefer to be more detached from general school operations. But other subs could interpret that distancing as a message that they are not really a part of the school culture. Principals and fellow teachers could welcome subs more directly, greeting them, visiting their classrooms, and making sure they know where to find a coat rack or a fridge for their lunch. Offering subs access to a break room and professional development also helps connect substitutes to the broader school community.

Opportunities for change

We also think it might be time for schools to consider alternatives to the current substitute teaching model.

Some districts pay regular teachers to cover for absent colleaguesduring planning or preparation periods. If this model is set up correctly, teachers substituting in other classrooms will have existing relationships with students and expertise in the subject matter needing to be taught.

Binghamton University, where we work, has developed a program called “Substitutes with a Purpose” in collaboration with regional educational leaders. This program sets up graduate students in education as substitute teachers, using that time to fulfill state requirements for in-classroom teaching.

We have found that this effort helps regional school districts address substitute shortages and helps university students earn money and fulfill academic requirements. It also provides an opportunity for these future teachers to become known in local schools, furthering their efforts to secure future full-time employment.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.