The Sonoran Desert National Monument is a spectacular representation of the Sonoran Desert landscape managed by the Arizona office of the Bureau of Land Management (BLM).

Recently the BLM has decided to open up the northern portion of the Sonoran Desert National Monument to livestock grazing.

On June 29, 2021, Advocates for the West filed suit against the Arizona office of the Bureau of Land Management for failing to protect the Sonoran Desert National Monument from the destruction of native plants, wildlife, and cultural resources by livestock.

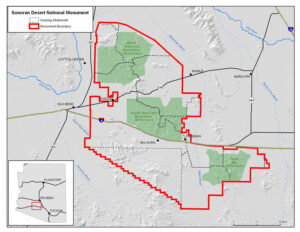

The red line shows the border of the National Monument, with the green areas showing the designated wilderness areas within the monument. Interstate 8 cuts the monument in two, with the northern half proposed for renewed livestock grazing.

I have visited the Monument several times since it was first designated. It is located south and west of Phoenix, Arizona. Interstate 8 splits the Monument into a north and south half. The south half of the Monument has not been grazed by livestock for many years. The Sand Tank Mountains in the Monument’s southwest corner is part of the Barry Goldwater Bombing Range and has been cow-free for fifty years. (It seems that only the military can get rid of cows on public lands).

Currently, there is no livestock grazing in the Monument. However, the monument declaration had a giant loophole that potentially could open up the northern half to livestock devastation. According to the proclamation, lands north of Highway 8 “shall be allowed to continue only to the extent that the Bureau of Land Management determines that grazing is compatible with the paramount purpose of protecting the objects identified in this proclamation.”

So, the question is whether livestock production is compatible with the protection of the numerous biological, archeological, and historical values of the Monument. Recently the BLM released a revised grazing analysis that proposes restocking the allotments north of I-8.

Western Watersheds Project and the Grand Canyon Chapter of the Sierra Club argue grazing is not compatible with the Monument’s purposes. They are plaintiffs in the Advocates for the West lawsuit challenging the BLM’s decision to permit livestock grazing in the Monument.

In reviewing the BLM’s justification for restocking livestock, one is struck by how much the agency has ignored independent science and even its previous evaluations that found the presence of livestock incompatible with the Monument’s goals.

DESIGNATION OF THE NATIONAL MONUMENT

Hiker in the Table Top Wilderness, one of three wilderness areas in the national monument. Photo George Wuerthner.

In 2001 President Bill Clinton established the 496,337-acre Sonoran Desert National Monument to protect an outstanding representative of the most biologically diverse desert in North America. The Sonoran Desert National Monument is considerably larger than the nearby 92,000-acre Saguaro National Park. Due to its monument status, the BLM can no longer manage the area like other federal multiple-use lands. It must protect the biological, archeological, and historical values for which the area was designated.

The North Mariposa Mountains Wilderness will be reopened to livestock grazing if the BLM decision is allowed to be implemented. Photo George Wuerthner.

In the proclamation for the Monument, the government noted the area “offer one of the most structurally complex examples of paloverde/mixed cacti association in the Sonoran Desert.” Beyond the saguaro cactus for which the Monument is famous, the area also contains desert grasslands and ephemeral washes, which support denser vegetation such as mesquite, ironwood, paloverde, and desert willow trees.

Desert bighorn sheep inhabit the national monument. Photo George Wuerthner.

The Monument is home to imperiled species like the Sonoran Desert tortoise, the Sonoran pronghorn, desert bighorn sheep. Other mammals that roam the Monument include coyote, gray fox, mountain lion, mule deer, javelina, bobcat, and numerous smaller mammals. Plus, more than two hundred species of birds are known to reside in the Monument.

In addition to the biological attributes of the Monument, there are numerous archeological and historical sites, including the Juan Bautista de Anza National Historic Trail, the Mormon Battalion Trail, and the Butterfield Overland Stage Route.

In addition to the stated mission of the Monument to protect these biological and historical attributes, the proclamation prohibits off-trail motorized use and closes the area to mineral claims. There are also three designated wilderness areas within the Monument: North Maricopa Mountains Wilderness, South Maricopa Mountains Wilderness, and Table Top Wilderness.

GRAZING HISTORY

Except for the Sand Tank Mountains, almost all of the lands within the Monument were grazed by livestock at the time of its designation in 2001. By 2009, grazing allotments south of I-8 were permanently closed to future grazing. Grazing in the remaining portion of the Monument was curtailed by 2015.

According to the Monument proclamation, the grazing allotments north of Interstate 8 can be grazed subject to a BLM’s livestock grazing compatibility analyses. Under the BLM’s decision, grazing will resume six allotments north of I-8, including the North Maricopa Mountains Wilderness and South Maricopa Mountains Wilderness.

Saguaro cactus is emblematic of the Sonoran Desert National Monument. Photo George Wuerthner.

Within the northern portion of the Monument, grazing authorization would allow for two types of grazing: perennial and ephemeral. Perennial grazing authorization allows for a certain number of cattle to graze the allotment during a specific period each year for the ten-year term of the permit.

The red flowers of ocotillo are a favorite of hummingbirds. Photo George Wuerthner.

Ephemeral grazing authorization allows for additional grazing on a seasonal basis when rainfall provides adequate forage. This ephemeral livestock use is particularly egregious since these rare flower blooms provide the extra vegetation for all of the Monument’s wildlife, from bees and butterflies to Sonoran Desert Tortoise.

Shortly after the monument designation, the BLM contracted with the Pacific Biodiversity Institute (PBI) and The Nature Conservancy to evaluate whether livestock grazing was compatible with the monument goals. PBI research indicated that the communities most heavily used by livestock had the most disturbance in the form of decreased vegetation cover, diminished native species diversity, high levels of non-native species—especially in forb and grass cover, and soil erosion and compaction.

Independent researchers concluded that there was no way to graze livestock in the Sonoran Desert NM without damaging the ecosystem and other resources. Photo George Wuerthner.

In a separate report, TNC concluded that no known grazing system is compatible with protecting the Sonoran Desert ecosystem and its resources.

Collectively, these rigorous scientific studies found that livestock was degrading soils, reducing plant diversity, increasing weeds and non-native plants, and damaging wildlife habitat on the Monument.

As a consequence of these studies, the BLM field staff wrote to the state director in October 2007 that: “livestock grazing is not compatible with the paramount purposes of protecting the objects of the monument and therefore the SDNM should be closed to livestock grazing.”

In October 2009, BLM drafted a Determination of Compatibility that again concluded livestock grazing was not compatible with protecting the objects identified in the Monument proclamation. In addition, the BLM concluded there were no feasible alternate grazing management strategies that would substantively reduce impacts, and therefore grazing was incompatible with protecting the Monument objects.

Unfortunately, the BLM directive was not finalized. Instead, the BLM decided to proceed with a Land Health Review to determine the ecological condition of the allotments located north of I-8 as a proxy to looking at how livestock might be affecting the monument resource values.

The BLM found that more than 128,500 acres constituting just over 50% of all Monument lands north of Highway 8 did not meet rangeland health standards for native plant communities.

Next, the BLM did an observational livestock use review from roads, what we called when I worked the BLM the “drive-by ocular method” of range evaluation. (Most range cons hate to walk–cowboy boots are uncomfortable for hiking). Based on dubious monitoring standards, the BLM asserted that livestock grazing was the causal factor for non-attainment of rangeland health on just 8,498 of the 128,500 acres. In the higher elevation paloverde-mixed cacti vegetation community, 21,539 of 87,366 total acres (25%) failed to meet the standard, and grazing was the cause on just 511 acres.

As a result of this review, the BLM did close 95,290 acres to livestock grazing but proposes to resume grazing on 157,210 acres.

HOW LIVESTOCK GRAZING IMPACTS THE MONUMENT

Livestock impacts on the Monument’s values are well documented. Livestock compact soils, inhibiting infiltration of water in an already arid environment and essentially increase the site’s aridity.

The hooves of livestock break up soil crusts. These biological crusts are essential for reducing wind and water erosion and also capture atmospheric nitrogen, which they pump back into the soil.

The Sonoran Desert is a harsh environment. It’s no place for domestic livestock. Grazing livestock here borders on animal abuse. Photo George Wuerthner.

There is no free lunch. The grass and other vegetation consumed by livestock leave that much less for native wildlife. In an arid land where biological productivity is already limited, the loss of vegetation can substantially harm native herbivores, pollinators and even reduce hiding cover for everything from reptiles to mammals.

By removing native perennial grasses, grazing can promote the establishment of shrubs and trees, altering the plant community structure of the area.

Many wildlife are sensitive to the presence of livestock and are socially displaced, including pronghorn, mule deer, and bighorn sheep. Displacement presumably pushes these animals into a habitat less suitable for their daily needs and thus indirectly impacts their overall fitness.

Saguaro cactus bloom. Photo George Wuerthner.

Trampling of saguaro cactus seedlings by livestock is common. Saguaro cactus typically rely on “nurse trees” to provide shade in its early years. Since cattle are attracted to the same shade, many young saguaro cacti are destroyed.

Cattle trample archeological and historic sites, destroying these cultural values.

Perhaps the long-term solution is to transfer the Sonoran Desert National Monument to the National Park Service, which is far less likely to favor livestock interests over the public interest. Photo George Wuerthner.

BLM DECISION

In July 2020, the BLM issued a final environmental assessment (“EA”) for the livestock grazing, which would authorize livestock grazing for the northern portion of the Monument. Accompanying the Final EA was a “Finding of No Significant Impact” (“FONSI”) that concluded BLM did not need to complete an EIS for the new livestock grazing amendment. It also argued that a detailed analysis of specific impacts on wildlife, vegetation, and cultural resources would occur at the implementation stage, making it more challenging to hold the agency accountable.

On September 28, 2020, BLM signed the Decision Record for the Resource Management Plan amendment. It adopted the proposed action—keeping the entire area north of Highway 8 available to grazing—as the final decision.

The plaintiffs argue the BLM once again the decision was arbitrary and capricious and failed to do a thorough and detailed analysis of the numerous impacts of livestock grazing.

Perhaps in the long term, the best way to protect the Sonoran Desert National Monument is to transfer it to the National Park Service since the BLM appears incapable of managing lands for national values.