“Space is not only high, it’s low. It’s a bottomless pit.”

― Sun Ra

The latest volume in Wakefield Press’ epochal Jean Ray translation project, 1932’s Cruise of Shadows, comprises both his biggest publishing flop and his best-known tales (The Gloomy Alley and The Mainz Psalter). Ray wrote the kind of cobbled-together eccentric pulp we now call “weird” fiction, mechanized fairy tales that operate along the inscrutable lines of a sinister gag: literally, a double of the modern bourgeois short story. The object of the best weird talent is usually money or some kind of con, but never art. It is far closer to a cheap clone or faked autobiography, at least in its Ray type (the other mode of true weird is pedagogic: a roman-a-clef integrity soldered onto a poiesis brut, with the aim of propagating something far beyond entertainment). Ray, just out of the joint for forgery and embezzlement, was therefore in the perfect position to concoct his greatest work. As parole makes for reflection, the spies, psychic vamps, and spectral informants littering the Cruise’s ruddy pages may be less ‘weird’ than more predictable spirits of probation.

The real revelation in the book is Mondschein-Dampfer, a mad Faustian clone which reads as if the author were eavesdropping on outpatients at 3 AM, then prying apart his own paragraphs to insert what he found. Food is the real preoccupation: sausage-smells and crusts, oozing sauces on plates, the stinking swell of garnishes and cures, and vinegar and curd chase ghouls with goulash. Ray is at his best here, a master of the locomotive potboiler scraped up from local cultic observation and then patched together so vindictively it works out of spite. The Mainz Psalter is too much Gordon Pym – brightened by a Méliès static verve and gothic jokes such as an evil clergyman who wilts down into his own cassock. The Gloomy Alley is a childlike vision of the occult zones of a city, where odd angles and narrow streets make non-Euclidean spaces. The tortured parasites of this sidereal quadrant haunt us just as we haunt them, giving a unique spin on ideas later found in gutsy pop TV like The Outer Limits. Most of Ray’s stories are built around that old 19th Century mainstay, the Found MS. (he also borrows the Dickensian technique of giving a fetishized life to inanimate objects, as in the stone lions in Tale of Two Cities etc). The Weird Professional turns the correspondence school of reportage into a purple set of inky confessions found in outrageous places – apartment walls, lockets, rotted desks in derelict ships, the hands of dying men – suitably atavistic and usually avaricious, always the product of theft or just deserts.

Translator Scott Nicolay[1] makes the canny observation that Jean Ray’s tales are basically old-school theatrical, ignoring any psychological drama in favor of groaning set-pieces. And they do read strangely stage-bound: stilted dialogue breaks up the diary scrap and malicious gossip; people are motivated only by revenge and covetousness; interior life is manifested by giant spiders, landlords and zombie cuckolds. Curiosity kills or makes mad and is the only drive permitted aside from greed. In true pulp style, ‘characters’ exist to directly produce sadistic effects – they are manikins on loan from London and Dumas, trapped in a repetitious arc of comic book panels and Protestant morality (this is especially true in Ray’s sole novel, Malpertuis, where it is grafted onto Robbe-Grillet trappings to please the Vague circuit). Any attempt to go beyond Dostoyevsky Lite and add problems of ‘conflict’ rather than curse are a grave mistake in the would-be Weird tale. Better to dwell on Tyrolean dinner specialties, incest, and Popular Mechanics-derived physics than any preciousness about Humanity (however, Formalism of the Russian kind might not be out of bounds). At its best, this makes for a good, vicious essentialism plagued by the author’s personal ticks.

aside from greed. In true pulp style, ‘characters’ exist to directly produce sadistic effects – they are manikins on loan from London and Dumas, trapped in a repetitious arc of comic book panels and Protestant morality (this is especially true in Ray’s sole novel, Malpertuis, where it is grafted onto Robbe-Grillet trappings to please the Vague circuit). Any attempt to go beyond Dostoyevsky Lite and add problems of ‘conflict’ rather than curse are a grave mistake in the would-be Weird tale. Better to dwell on Tyrolean dinner specialties, incest, and Popular Mechanics-derived physics than any preciousness about Humanity (however, Formalism of the Russian kind might not be out of bounds). At its best, this makes for a good, vicious essentialism plagued by the author’s personal ticks.

Probably the last real Ray-like jobbers were the writers of those benighted film tie-in books (Ray wrote an impossible-to-ascertain amount of pulps featuring Harry Dickson, an American Holmes mugger, so it isn’t too farfetched to picture him cranking out Kojak paperbacks or a novelization of Warlords of Atlantis). But without an eye for material need, a potboiler-maker can only fall back on the dreadful middle brow, puffing out near-ghosts like Andrew Michael Hurley’s The Loney – a windy, eerie and mannered horror vacui just waiting for a del Toro to overstuff it on screen. If Ray ever gets the Hollywood shuffle, it would probably drown in half-digested postmodern protoplasm, all handsomely lensed[2].

So what is Weird Fiction really? Does Thomas Hardy’s Return of the Native count, or is that ‘folk horror’? And Strange Tales from a Chinese Studio? The Bible? Being anti-canon is no longer enough. And Serious Poet-types should remember that TS Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral is basically an Agatha Christie rip-off with Common Prayer aspirations. No surprise, as Eliot was in banking, a profession tied to ancient blasphemies and subversive cults. Das Kapital also has its fair share of Cyclops, werewolves, and haunted Houses of Pain. The weird is never confined to the Weird proper, I hazard. Or like Jean Ray’s billion noms de plume, the Weird is so vast that it encompasses everything, while deviously positing itself as mere genre.

The real kick in translator Scott Nicolay’s Jean Ray project is that he clearly enjoys pushing the clubs, making questions of who’s in and who’s out rib one another, and generally causing trouble like the Maestro himself. Nicolay argues in his excellent Afterward that the Weird is still too centered around the old Weird Tales magazine, a vigorous Golden Age pulp that loosed Cthulhu, Conan the Barbarian and Hannes Bok on the world. Nodes outside the West tend to be ignored (Hedayat’s Blind Owl and voodoo’d works of Amos Tutuola make HPL’s Arkham look like Branson in comparison), perhaps because the Weird tastemakers are monoglots who know little beyond the Necronomicon. So, what is the Tamil Weird like? Where is our Wolof Weird? Besides, it is probably impossible by now to truly reckon the original American Weird circle, given the countless trendy film adaptations and nihilistic cults that have arisen – Nyarlathotep be praised! – around their provincial mythos. Maybe gentrified properties like Lovecraft should be ceremoniously ushered out of the Weird and into Marketable? After all, if the canon has been stretched, does it not also demand contraction?

Being that Cruise of Shadows is a truly seminal instance of Weird – as well as an omen warning of too much self-consciousness, evident even back in the ‘30s – we see in it another cardinal rule: No pulp author should read too deeply in his science, anthropology, physics etc. The most facile ideas are more than enough to propel the action, as well as a weirdling remove. Revelations of an off-kilter universe must read as if the author stole the idea from a freak news story, then plagiarized it half-digested and cranked out two sequels. Same goes for philosophy and painting. Also, mind your pastiche!

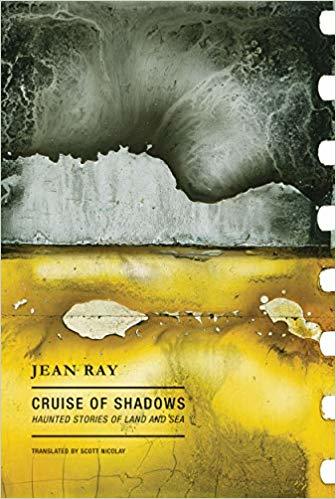

Wakefield Press’ striking edition evokes biology with its colorful nitrate flare cover: the timely idea of cruise liners beset with virus? Ray would no doubt have rushed a Corona-inspired quickie off in honor of our contemporary nightmares of infection, Chinese whispers, and the agonized hosts of luxury.

Notes.

1) In addition to an excellent blog on the Weird matters, Mr Nicolay also hosts an engrossing horror podcast, The Outer Dark. He represents an heretical school in the fantastic genre – I would certainly say a Left flank – and has gotten flak for it from the Old Guard (e.g., ST Joshi). And if you can track down a copy of his very beautiful translation of J.-H. Rosny aîné’s indisputably strange The Xipéhuz, you will never regret it. ↑

3) Malpertuis was in fact filmed in his homeland in 1971, with some genuine dizziness and Orson Welles. ↑