The writing of Ishmael Reed blows my mind. It has done so since I first read his masterful novel Mumbo Jumbo when it arrived in my favorite bookstore. The sharp edges of his insights and the satirical swipes that define his commentary (fictional and otherwise) cause my belly to laugh and my brain to engage. His manner of turning US society and its culture upside down and then shaking it onto the floor like the cat litter it can often be never fails to provoke. The fact his works are not read by more across the land is to their detriment. Then again, all too many would fail to find the humor in his narrative. That is the state the USA is in this summer of 2021. Right on schedule, Reed’s latest installment in the book series he began publishing in 1999 with the title The Terrible Twos is on the shelves (so to speak.) The book, titled The Terrible Fours, is a clever, bitingly sharp and unconventional reality show of the nation Donald Trump both made and undid. It’s not pretty, but it is as funny as Richard Pryor, as sacrilegious as Lenny Bruce and as clever as Mark Twain.

Characters from the previous two titles in the series—The Terrible Twos and The Terrible Threes—spill into Reed’s latest challenge to the satisfaction with self-destruction that describes the land of the free and the home of the knave. The basic framework—the context, if you will—of these novels is the consumer society of the United States; a society where instant gratification is a religious duty and Christmas is every day. St. Nicholas and Black Peter (the real one and an impostor) zip in and out of the tale. The wealthy and powerful are played as much as they play on the media-driven stupidity of those who follow the escapades of the rich and famous. The cast includes a minister of the holy Jesus working for the Devil and cabals of twisted white supremacists conspiring to destroy their mistresses and the surplus population. There are Black men and women working as double agents in the race war the white supremacists don’t want to end. There are extraterrestrials in earthly form removed from earth to their home planet in an event interpreted as the beginning of the Rapture by the servant of Satan in the White House—a servant who thinks he controls the Faustian deal he has made. While it is possible to read this latest installment by itself, I recommend the reader read them two, three, then four. The essence of the vision of Ishmael Reed might then begin to be appreciated.

In the spring of 1979 a friend and I rode a Greyhound bus from Oakland, California to Atlanta, Georgia. We had smuggled some whiskey and weed onto the bus to ease the discomfort and help the time pass. After passing through Texas and Louisiana, we headed into Mississippi. We had a layover in Jackson, then got back on the bus for the final stretch. After Jackson, the bus became a local. We stopped in every goddamned hamlet and town in Mississippi. They looked mostly the same. A small market, a post office, shiny big sedans, battered pickups and folks going about their business in the steamy warmth of a Mississippi April. Many of these places shared another similarity. One side of town had nice houses built in a certain southern style; think the plantation massah’s house on a slightly smaller scale. The other part of town was different. The houses were one and two room cabins with wooden steps and greased-paper windows. The plumbing involved a hand pump and a wooden outhouse. Many of the streets were unpaved and ditches on either side were running with muddy water. The residents were poor and mostly Black. It really came home to me that William Faulkner’s Mississippi was as real as his canon of  novels.

novels.

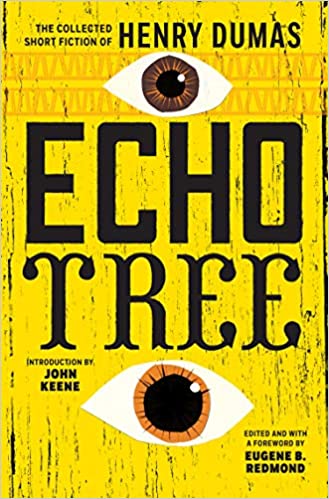

The stories of the writer Henry Dumas bring that same weary Southern landscape alive. The characters in his tales are mostly Black and poor. Mostly, they live in the woods and hamlets of the US South. Only a few of the stories in a recently published collection of those stories—titled Echo Tree after one of the stories therein—take place outside of this territory. Those tales locate themselves in the Harlem of the 1950s and 1960s and reflect the disharmony and anger that boiled over during that time. Dumas, who was murdered by New York Transit Police in 1968 at the age of thirty eight, was often identified with the Black Arts Movement of the period. The artistry of his words in this collection evoke the steaminess of the southern summer and the oppression of US racism. Perhaps it is his words describing a scene in Harlem before the police attack a crowd that express this world best: “Even small children were infected by the malady of hate and boredom.”(166)

Dumas’ prose is affectingly aching and absolutely arresting. This reader was transported into the ecology of relationships between people and the land by these stories. The odors of the swamp and of the fear of the white man with a shotgun became as real as the gulls screeching outside my window. The human hope shining through a hopeless world of racism and poverty is present without annotation. Henry Dumas’ stories are a freedom song and an angry cry. A history lesson and a country walk. A policeman’s club and a cracker’s shotgun. They are a United States of America that has yet to go away and lingers on that red, white and blue flag like a wound that will not close and refuses to heal.