Paradise Church, Micanopy, Florida, 2022. Photo: Harriet Festing.

Billy the carpenter

Billy is around 60 and a skilled carpenter, among several we hired in 2019 when our house in Micanopy, Florida was being built. He’s tall and lanky, chain smokes, coughs, and has a working-class Georgia accent. He often teased me about being Jewish. He was poor and Jews are rich, he told me conclusively. I was cheap and he was generous, he said. In fact, he demonstrated his prodigality one afternoon by offering me a gift of some of his medical marijuana. I refused it, thinking I was protecting his valuable stash, but I realized afterwards I may have insulted him. One day, I told Billy that a crew of window-washers was coming, so he’d have to stay out of their way.

“You mean the [N-word] ones, from Gainesville?”

“Billy, don’t use that word. That’s horrible.” I admonished.

“If that’s what they are, and if they’re comin’ here, I’m goin.”

“What’s gotten into you?”

“I don’t work beside no [N-words]”

“How can you talk that way? What would your wife and daughter say if they heard you now?”

“Well, they wouldn’t like it, but they know I ain’t prejudiced – I just don’t like [N-words].” He paused and added: “I voted for Obama.”

“That’s surprising. Did you vote for Trump?” I asked.

“No, I hate that guy! He ain’t done shit for me or any other poor man. I’ve got a sick wife and I can’t get Medicaid or Obamacare.”

“So that’s why you don’t like Trump, because he hasn’t expanded Obamacare in Florida?”

“Yeah,” Billy answered with a smile, “and because he’s a racist!”

Mrs. Taylor

Two years ago, when I was running for a seat on the Micanopy Town Commission, I went to see Mrs. Taylor, an elderly white woman down on Tuscawilla Road, to ask if she’d put up one of my yard signs. Her house, two-stories high with a balcony at each level, was set far back from the road and framed by a pair of ancient live oaks with great candelabra branches bedecked with Spanish Moss. In lieu of a lawn, she had a mix of sunshine mimosa and frog fruit; both were flowering, pink and white. I knocked on her door and she opened it almost at once.

“Mrs. Taylor, how are you? Your garden is looking fine these days” I began.”

She smiled faintly. I hesitated but then said: “I’m here to ask for your vote and if you’d take one of my yard signs.”

“I’m not voting for any P. H. D,” she said, practically spitting out the three letters.

I hesitated a few moments, and then asked: “How do you know I have a Ph.D?”

“I just know.”

“Um, may I ask what you have against people with Ph.Ds?” I continued.

“Nuthin’, I just wouldn’t vote for ‘em,” she answered, as if it was good common sense.

“Can I at least tell you why I’m running – tell you about my platform?” I persisted.

“Nope,” she answered. “I won’t vote for any doctor.”

“I’m not a medical doctor,” I reminded her.

“I know,” she said, and then repeated: “You’re a P.H.D. and I’m not voting for you!”

I lost by 17 votes to the conservative candidate. A few months later, I saw a Biden/Harris sign on her yard. I guess she just doesn’t like Ph.Ds.

Abandoned house — the oldest in Micanopy built by Black people for Black people. 2022. Photo: Harret Festing.

Jim Rollins

Last March, there was another election for Town Commission. This time, I chose not to run and was rewarded for my discretion when a pair of progressive Black women defeated two conservative, white candidates, changing the political as well as racial complexion of the five seat Commission.

A few days before the election, however, I had a strange encounter. I was driving down Easy Street — that’s really its name (there is also a Lucky Ave) — when I saw Jim beside his ramshackle house, with car and tractor parts on the front yard. He motioned to me to stop and roll down my window.

“Hey Stephen. Why did all those white cars stop at your house last week?”

“White cars?” I asked.

He moved a little closer and bent down to speak more confidentially: “The seven white cars loaded with Black people who got out and went into your house.”

“Jim, I’d gladly welcome seven carloads of Black people into my house, but it never happened. Who’d you hear that from?”

“My friend, Hiram” he said. “He patrols the neighborhood in his golf cart — keeps his eyes open.”

“I’m sure he does,” I said. “But in this case, he was mistaken. If I were you, I’d ask him to get some eyeglasses.”

He looked disappointed and doubtful. Before I drove off, he leaned over again and whispered: “Just be careful who you let into your house.”

Mr. Wilson

One Spring day, I was riding my bike down Whiting Road when I heard a chain saw. I detoured to follow the sound down a side road toward an old grey Cracker house on a large lot. I wanted to make sure nobody was illegally cutting down one of the town’s many, legally protected live oaks — it’s been known to happen. An old, stout white guy was standing precariously on a tall ladder, trimming the lower branches of a Water Oak. The species is native to the area but unloved – and thus unprotected – because it has a habit of falling over for no apparent reason, crushing anything or anybody beneath it.

“Afternoon, sir.” I called out, during a pause in his trimming. “Mighty hot for yard work,” I added, unnecessarily, and introduced myself.

“Yeah,” he answered and carefully descended the ladder. “I’m Mr. Wilson.”

I wondered if we’d met before — maybe in Town Hall or at the Post Office? “Nice old house, this one. Lived here long?” I asked.

“Almost my whole life. I grew up in it, went away, and came back.”

He had a strong Southern accent – I guess it was a Micanopy accent. “Wow. I imagine you’ve seen a lot of changes in town over the years.”

“Yep, and all for the worst.” He answered forcefully. “Like all those new ordinances that prevent you from doing what you want on your own property.”

I didn’t let on that I was one of the people always proposing ordinances limiting property rights. “Property is theft,” I thought but didn’t say. Proudhon’s slogan has long been underappreciated.

“And last year,” he continued, “some fool wanted to build a pool in town. We don’t need to spend money on no damn pool!”

Did he know it was me who proposed building a town pool when I campaigned for Commission? Is that when I met him?

“And we used to have a general store, over on Cholokka” he said, pointing vaguely to the east. “I worked there as a kid. This year, the commission and a bunch of local idiots prevented Dollar General from opening a store here. We coulda used a store like that.”

Was he having me on? I was one of the people who fought to keep the store out of Micanopy. I parried: “Yeah, but that wouldn’t have been a real general store. They don’t even sell food, except junk food. And they pay terrible wages.”

Determined to find common ground, I continued: “I bet you knew folks who worked in the old Franklin Crate factory here that closed about 20 years ago.”

“Yeah,” he said, “my cousin worked there, making baskets.” But it was mostly full of Mexicans, illegals. They need to keep them out – they come into the country selling fentanyl and other drugs.”

Now I had to take a stand. ‘No,” I said, and added a cultural cliché of my own: “Most Mexican immigrants are hard-working people. Besides, the farmers and horse breeders around here rely on them.”

“Well then,” he replied, “they should come in the right way, legal.”

“I agree,” I said, “let them all in legally.”

“OK but build a big wall first,” he added.

We’d run out of things to say. I wished Mr. Wilson good afternoon and rode off.

J.D.

J.D. was an odd jobber on the site where my house was built. Most days, he arrived early and stayed late and didn’t grouse to his boss about anything he was told to do. He spent his time sweeping, unbuilding the mistakes made by the various contractors, and cutting holes in concrete. He’s about 60, I guess, but with the muscled frame of a man 20 years younger. When we spoke, he was polite and self-deprecating, and sympathetic when I complained about how slow the construction was going. Sometimes we talked about our families. I enjoyed hearing him – in his thick Southern drawl – expatiate upon the genius and grace of his young niece, the abundance of his vegetable garden and the strange plants that grew in the swamp behind his house – he knew I was interested in Florida native plants. He promised to bring me a pitcher-plants when our pond was dug.

During lunchtimes, J.D. would retreat to the shade of his truck and listen to Rush Limbaugh, Glenn Beck, or some other right-wing radio personality.

“JD, how can you listen to that stuff? You are such a kind man and Rush is so nasty.”

“I don’t really listen – it’s for entertainment.” He answered.

“You mean you don’t believe what he says?”

“Sometimes I do.”

I pushed a little further. “Even all that racist and anti-Semitic stuff about Black Lives Matter and George Soros?” I was faking it – I’d never in my life heard more than 30 seconds of Rush or Beck.

“Naw, I’m not racist. I grew up here in Micanopy and when I was little, my best friends were Black kids. Some of my best friends now are Black.”

“Weren’t the schools still segregated when you were a kid?” I asked.

“Yeah, but after school, we all played together and hung out together.”

After the house was finished, I didn’t see much of J.D. I suppose he’s still doing construction, though he said he was thinking of working on a nearby cattle farm instead. He loves animals. He forgot to bring me a pitcher plant.

Jeri (Black, not white)

During the election last year for Town Commissioner, I got to know a few more of the Black residents in town. One of them, Jeri, has lived in Micanopy for most of her 75 years. She’s a retired civil servant and a widow. I asked her what the town was like for Black kids in the 1960s and early 70s, during the era of segregation and just after. We discussed the fact that while schools were legally de-segregated by the Supreme Court in 1954, it wasn’t until decades later that the curse of educational apartheid began to be lifted in the South.

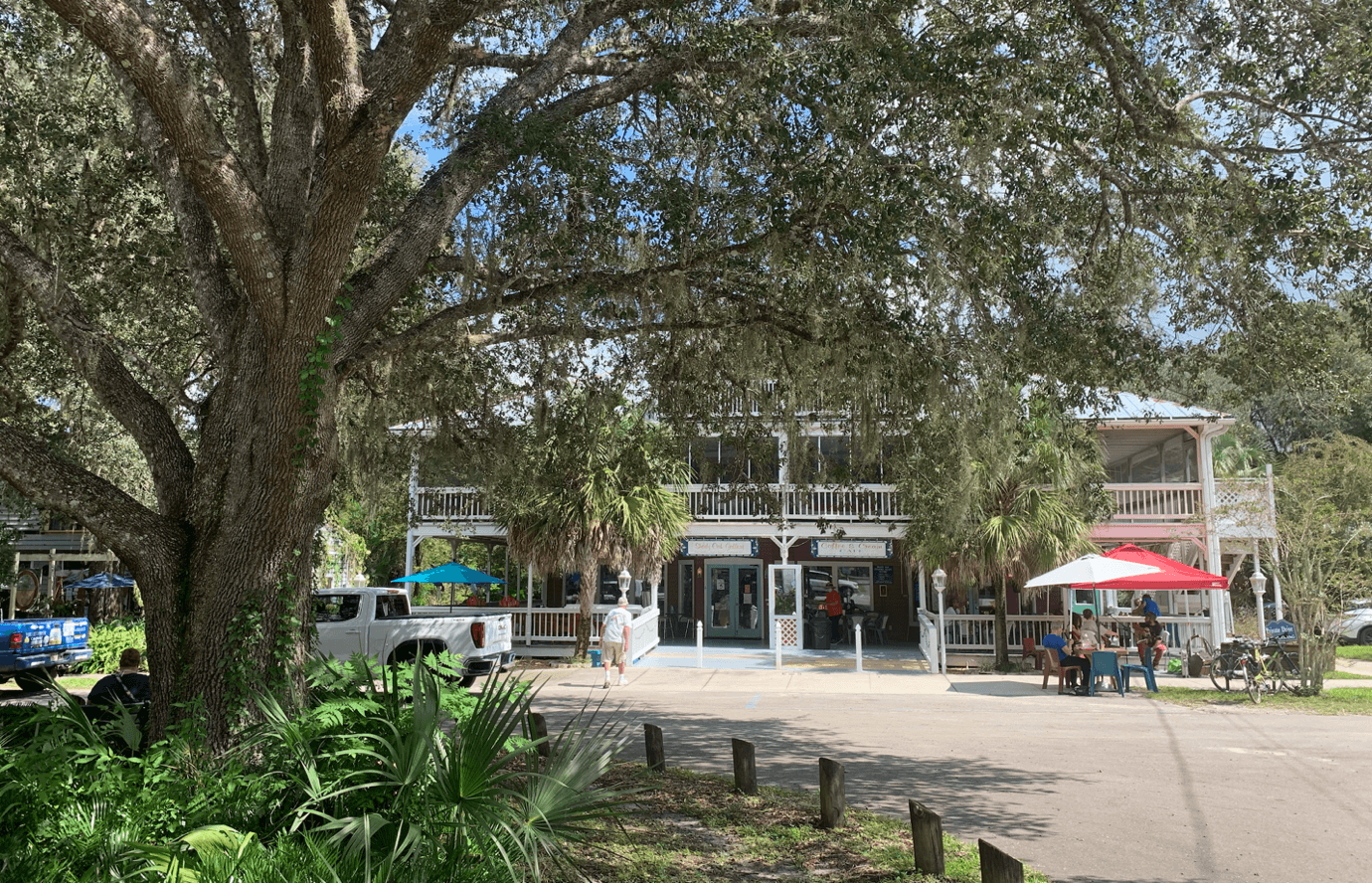

A view of downtown Micanopy, 2022. Photo: Harriet Festing.

“What was it like for you, growing up here?”

Jeri lifted her glasses, sighed, offered a half-smile, and answered: “It was as you said. Micanopy like everywhere else around here, was segregated – schools especially. Mind you, the crate factory was integrated, so the men who worked there developed friendships with people of a different race. But for us kids, it could be hard.”

I continued to probe: “But my friend J.D. said Black and white kids all hung out and happily played together – that segregation was left behind once school let out.”

Jeri’s eyes widened and mouth opened: “Well, of course, he’s younger than me, but I remember playing with my Black friends in front of the old General Store and white kids upstairs leaning out of windows throwing things at us and calling us [the N-word].”

I was pretty stunned to silence. Then I managed only to say: “I guess maybe people have different memories of things.”

“You’re not kiddin’” she said.

“But you stayed here in Micanopy.”

“My family is here,” Jeri replied, “my friends are here and it’s beautiful. Why should I leave?