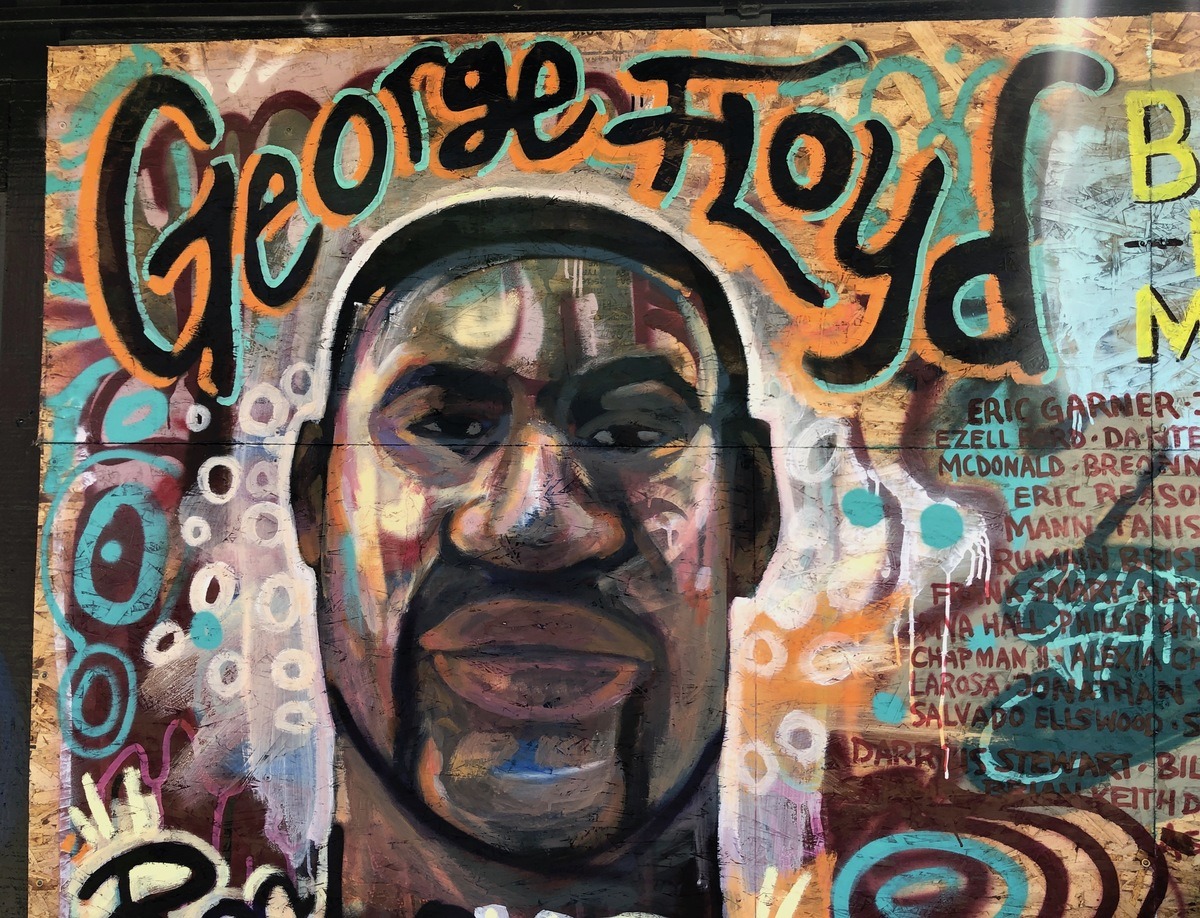

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

Exactly a month after George Floyd’s death, driving along Sunset Boulevard in Hollywood, ‘Black Lives Matter’ tags have converted the plywood board-ups that line the street into a tapestry that establishes a rhythmic mantra – proclaiming a society of equality and justice. Approaching Crescent Heights Boulevard, the currently closed Laugh Factory is covered with images of George Floyd as though he were the featured stand-up comedian at the club. Floyd, however, achieved his eight minutes, forty-six seconds of fame with his neck pinned to the ground by a white police officer’s knee. His life was unregarded and his potential death, as his last moments ebbed away, entirely ungrieved by his assailant.

That his life mattered, and now continues to matter, has been fully established. On Sunset, his spray-painted, chiaroscuro image appears repeatedly on either side of the road as it passes through glitzy Sunset Plaza and then curves uphill past music clubs, boutique hotels, and restaurants, over all of which loom huge billboards that, like mechanical raptors, appear to be surveying their prey – but it is Floyd’s face, at eye level, amidst the BLM tags, that commands a deeper, visceral attention. All this changes abruptly as the road begins its meander through residential Beverly Hills, Bel Air and Brentwood. Here, manicured trees, groomed yards, and neatly trimmed hedges obscure the grand houses which shelter those entirely untroubled by the precarity experienced by many, perhaps most, Americans.

Here too, no doubt, ‘Black Lives Matter’ is also having a moment – the Kindles of its residents loaded or their coffee tables scattered with appropriately themed books, like the seven of the ten that command the NYT hard-cover non-fiction best-sellers (as of May 31 – June 6): White Fragility, Robin D’Angelo; So You Want to Talk About Race, Ileoma Oluo; How to be an Antiracist, Ibram X. Kendi; Me and White Supremacy, Layla F. Saad; The New Jim Crow, Michelle Alexander; Between the World and Me, Ta-Nehisi Coates; and, Becoming, Michelle Obama. Feelings of earnest concern, genuine sympathy, resolve to make a better world, and a sense of solidarity, surely prevail.

However complicit we may be in sustaining the historical-racial schema in this country, we can all now agree that, ‘Black Lives Matter’, but the tag’s emblazonment across the country, and internationally, remains a hollow gesture unless there is meaningful collective action to create a social environment in which all black lives can indeed flourish – and matter. Southerners lost the Civil War but won the peace by instituting one hundred years of Jim Crow. After overthrowing Reconstruction, white Americans colonized the freed slaves, exploiting their labor, denying them their democratic rights, and policing their lives with state sanctioned violence. It is thus that the Civil War continues. It is a war about an equitable share of the nation’s wealth and, perhaps as importantly, societal respect. The psychiatrist, Frantz Fanon, in, The Wretched of the Earth, 1961, suggests that the eponymous masses, under the heel of European colonization, rebel not only against need and hunger, but the continuing humiliation to which they are exposed. While the condition of Black America is surely as varied as White America, the former carries with it the accumulated inheritance of four hundred years of humiliation (established in 1619), barely dented by the election of a person of mixed heritage as president in 2008. White America carries with it, in even its direst subjects, the taint of unassailed privilege (established in 1492), in which, as a white immigrant resident here for some forty years, I undoubtedly share.

Judith Butler, the U.C. Berkeley academic and author (blurbed by Cornel West as, “the most creative and courageous social theorist writing today”), is unlikely to appear on any New York Times best seller list. But her new book, The Force of Non-Violence – An Ethico-Political Bind, published earlier this year, directly addresses the issues surrounding the murder of George Floyd. She frames the possibilities of non-violence in American society within the concepts of ‘livability’ and ‘grievability’.

She writes that, “…equal treatment is not possible outside of a social organization of life in which material resources, food distribution, housing, work, and infrastructure seek to achieve equal conditions of livability. Reference to such equal conditions of livability is therefore essential to the determination of “equality” in any substantive sense of the term.” These conditions of equality must be achieved outside of the shadow of colonial power falling on a population and thus rendering them dependent. “That deployment of dependency confirms both racism and colonialism: it identifies the cause of a group’s subordination as a psycho-social feature of the group itself.”

Butler argues that non-violence is untenable unless it occurs within a society committed to equality. The equal value of life is its essential condition – otherwise, as she notes, “certain lives will be more tenaciously defended than others.” It follows then, “If one opposes the violence done to human lives, this presumes that it is because those lives are valuable” – their loss, in any circumstance, is made worthy of grief. All members of a society founded in equality will then possess ‘grievability’.

Butler uses the frame of grievability to review the death of Eric Garner, a black arrestee put into a choke hold in New York City by a white police officer while the victim gasped, “I can’t breathe.” This 2014 tragedy helped to catalyze the national ‘Black Lives Matter’ movement. In an analysis that directly relates to the murder of George Floyd, she asks, “…is it simply that this life is one that can be snuffed out because it is not considered a life, never was a life, does not fit the norm of life that belongs to the racial schema; hence, because it does not register as a grievable life – a life worth preserving?” After a Staten Island jury failed to convict the N.Y.P.D. officer responsible for Garner’s death, William Barr, the Attorney General, chose not to pursue a federal civil rights indictment against him.

What establishes solidarity is mutuality – a common desire to live our lives un-threatened by each other; a recognition that it is only the establishment of the universal grievabilty of life – all life, human and non-human – that will ensure our survival as a society and as a part of the global ecosystem. Thus, it is that Judith Butler expands the thesis of her slim volume to register the enormity of America’s, and humanity’s challenge.

The Force of Non-Violence ends with what may serve as a requiem for George Floyd,

“So, whether we are caught up in rage or love – rageful love, militant pacifism, aggressive non-violence, radical persistence – let us hope that we live that bind in ways that let us live with the living, mindful of the dead, demonstrating persistence in the midst of grief and rage, the rocky and vexed trajectory of collective action in the shadow of fatality.”

That is too long for a tag, but it seems to me to be the full flowering of what ‘Black Lives Matter’ can mean: it represents its lived destiny – its ontogeny. If we can embrace the ‘vexed trajectory of collective action’ implied by these three words, now imprinted on our urban infrastructure and on our consciousness, we might begin the difficult work of transformation required of them.