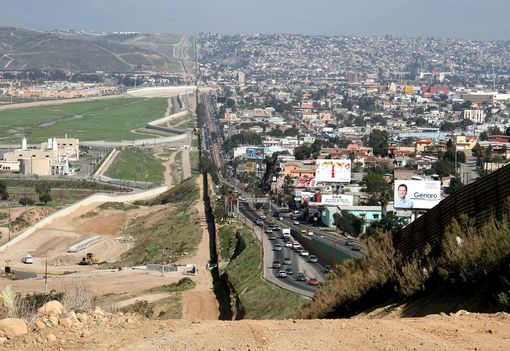

Photograph Source: Sgt. 1st Class Gordon Hyde – Public Domain

A solution to the border crisis is impossible without a comprehensive overhaul of the immigration system. Thomas Friedman suggested what one might look like after his onsite inspection of the San Ysidro border with Tijuana recently. Arguing against the random and chaotic system we have now, he pledged support for a “high wall” but also a “big gate,” insisting we must find a way to efficiently absorb those who will bring the skills and knowhow to strengthen our nation. Perhaps realizing this will constitute a sizable pool, he endorses aid to the countries where the bulk of migrants are coming from to stabilize their societies, as well as a revamped court system that can fairly process deserving asylum seekers (Thomas Friedman, New York Times, 4/23/19).

Getting tough on entry, like most other nations, while continuing the legacy of welcoming immigrants began soon after the country’s inception, is a kinder and gentler approach to exclusion than Trump’s “America First” vision, which translates to a quite brutal practice, and a rebuke to the America Diverse vision from many Democrats that invites virtually all comers, whether applicants for citizenship or escapees from unstable environments. Given Trump’s views on abortion he would perhaps be best served by going along with these Democrats and let large families of pro-life billboards spread through the hinterlands.

Friedman offers a passable general outline of a “solution.” Unfortunately, there’s no political will in Congress to act. The last major piece of legislation was passed in the Reagan administration. President Obama urged Congress to act early in his first term but was forced to settle for DACA, his 2012 executive action. Trump’s efforts to cancel this initiative through executive actions have spearheaded his aggressive campaign which is ironically not all that different than Obama’s in terms of the numbers of people deported, but the issue of treatment and family separation is another matter.

What alliance of political voices will decide who the deserving are and what skills are needed? Should this task be left to the private sector, specific profit-driven companies that serve their own constituents first, to make it happen? Enlightened wonks sustained by the clout of peer-driven, but far-from-neutral research? How will the formula be constructed for determining how many should be processed? What’s too little; too many?

One thing for sure, the elites who decide these issues and whose employment is secured will not be impacted by the consequences of their choices.

A familiar refrain is that there are many labor jobs to be filled that existing citizens can’t or won’t do, and therefore we should keep these paths open. The value these workers put into the economy will benefit the larger society. This logic is at odds with Trump’s nominal position—as opposed to his scattershot policy directives that support exclusion—that those here deserve priority, and a restricted labor force can deliver value to them in the form of higher wages. So as migrants swell a labor market these citizens can experience real threats—some jobs are definitely taken in certain situations—and a glut of new arrivals can suppress wage levels.

The perennial problem with American capitalism is that its logic of differential rewards dispensed to different sub-classes and ethnicities in different regions over time is an irrational practice that pits people and groups against each other instead of the system that’s responsible. This is hardly conducive to a welcoming synergy. And since wages are relatively low for labor the influx of new workers into the economy has a tendency to make current residents uneasy, especially since new arrivals can be willing to work for less and this can lead to real job losses. But even if citizens never actually lose jobs to new arrivals they might constantly feel the existential threat of loss and be susceptible to politicians that stir up xenophobic sentiments. The facts about where the labor shortages actually are for migrants to fill might therefore be of little concern to workers at the lowest levels caught in this vortex. And inequality is so deep and pervasive now that few can imagine what a fair economy might look like. Reason can easily be replaced by the absurdity of resentments.

Barack Obama stated in a celebrated 2008 speech on race and class that if America is ever to become a free and equal country where all ethnicities exist in harmony to identify with one nation (the many in the one, e pluribus unum), we must get rid of the resentments that individuals and groups harbor against each other because they feel someone else’s gain comes at their expense. To extirpate this bad dialectic is a formidable task since the capitalist system is structured through a language of trade-offs. Capital is generated and executed through differentials, especially the gap between acceptable—defined of course by those who own it—profit levels and wages. Wages that are too high threaten to dry up capital and investment. If resentments are to be modulated and we approach Obama’s win-win vision the extreme inequality that now exists must be corrected. Arguably, this will mean the end of capitalism as we know it and at least the beginning of one that forces capital and communal values to coexist. This isn’t going to change in time to transform ICE or cancel the family separation policy at the border. But if a comprehensive overhaul is to succeed in the long term the imbalance of excessive profiteering which fuels resentment has to be managed.

Not to mention imbalanced policies. The spectacle unfolding at the detention centers is worth noting. The horrific, prison-like conditions the detainees are being subjected to have been well documented. Calls to improve these conditions and give the detainees good healthcare ring eminently humane and rational. But how ironic is it that millions of American citizens at this moment are suffering the same deficiencies. How do we expect these victims to react to the implementation of improvements for those who are not citizens? Without attention to the gaps and insufficiencies in our current system that are pasted over by the “great economy” rhetoric, the win-lose dynamic will persist in spawning resentment.

The sectors of the labor markets that need workers have to be accurately identified. Letting the markets (owned by interests and hardly free and equal arbiters) dictate movements can produce chaotic reversals for citizens who lack the means to fight back. They can experience these events as virtual acts of war against them. They can become the vehicles of a kind of blowback, venting and spreading their frustrations as victims through groups and communities, weakening rational resolve and seeding suspicion and the sense of imminent threat like a contagion. Like in war, when the reciprocating deaths accumulate to the point where revenge explodes into a self-feeding frenzy and the issues that led to conflict are no longer known or of interest.

Evidence that President Trump is not simply anti-immigrant would seem to come from his statements about northern Europe. He welcomes those from the countries that are successful, “good” countries that send us credentialed professionals to, echoing Friedman, help us strengthen our nation. These homogenous countries are successful to a great extent of course because they’ve managed to—relatively—solve the inequality problem, though some certainly come here for the lower taxes. But this position would seem inconsistent with “America 1st.”

Do we have a shortage of people to fill the grad schools for educating the professional workforce? The competition for these slots and the positions sought with the education is fierce, as is simply getting into college. This might help explain the degree to which parents are now going to get their children admitted, especially into the elite colleges and universities. The difficulty of getting into college for many is amplified by the practice of state-funded institutions to recruit students from overseas due to austere, budget-cutting policies dependent on higher out-of-state tuition. What does this do to the hard-working student from an extended family where no one has gone to college before who is denied admission?

Friedman’s globalization endorses the seemingly rational notion that all countries benefit when “the best” can cross borders to fill needs one country can’t, justifying the selection of sports figures, for example, and even medical doctors in demand because their pool is kept artificially low here by the AMA (not to mention the admission of students from elsewhere who often return to their home country, making it more difficult for those here to get in). This system has little space for “the worst” who lack the equal ability to move across borders.

A byproduct of this fierce competition is underemployment. While few deny the value of bringing professionals who possess the skills and training needed here, the stark reality is that many with advanced degrees are forced to work at jobs well below their qualifications. This is an especially serious issue among millennials who have to live with their parents while scraping together a living, but according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics this experience isn’t unique to today’s college grads. The rate for all college grads ages 22-65 has held steady at around 33% for the past three decades. And for the grads ages 22-27, the numbers rise to 44% (Jessica Lutz, Forbes, 7/21/18). The situation is even worse for people of color.

These numbers are not a prominent part of the official stats which unfortunately become the final word on the state of the economy, sending proof-positive signals to all readers of the mainstream media that we need and can absorb more workers. But as Jack Rasmus shows in his evaluation of the Bureau’s recent numbers, the underemployed and other less-than-full-time employed persons are counted as employed (CounterPunch, 5/8/19, “How Accurate Are the US Jobs Numbers?”).

The markets for labor jobs and professional jobs are obviously different, but as college grads take jobs from those below them these workers in turn can put pressure on those below them, etc. Obviously this will reach a limit and few will do jobs that far below their level of competence. Many caught in this situation simply drop out of the work picture and remain hidden in the official unemployment rate.

But the larger issue is the build-up of resentment by those unable to fulfill their potential in the workplace and be fully absorbed into mainstream, everyday life. Whether college grads or the rural working class living in once thriving zones now de-industrialized and de-unionized as a result of companies rushing to capture cheaper wages in the overseas sweatshops, their experience of this structural flaw in the American Dream can only be amplified by witnessing others streaming into the country—compounded by the presence of millions of illegals—who may not even be directly responsible for taking someone’s position. This can clearly breed scapegoating, which perhaps explains the recent Harvard-Harris poll. This showed that 81% of registered voters want annual immigration reduced by nearly a third to check the “chain-migration mess,” and 70% want the random and liberal issuing of visas to cease (Eddie Scarry, “Thomas Friedman Joins America,” Washington Examiner, 4/25/19).

The country is not the same as it was during the golden days of capitalism, the American Century, when progressive tax policies, strong unions, and Keynesian innovations in the public sector allied to increase productivity, and the value from that was distributed much more evenly and fairly. Aggregate upward mobility has been one of the casualties, particularly in the rural areas, despite the celebration of specific instances of entrepreneurial mobility in the media. We’ve become a sort of unmelting pot with a diversity of segments that can’t be easily absorbed into the mainstream, and like many of those forgotten citizens that spearheaded Brexit, they’re not happy with the status quo (Huffpost, “Unmelting Pot,” 5/25/2011).

Friedman is a celebrator of globalization, believing there is virtually no alternative to this mostly benevolent march of progress, but this world system itself, in the current form shaped by American hegemony, is the cause of many problems. The export of neoliberal principles creates failed states from these developing countries that send bodies to the “stable” ones for refuge. The extension of economic influence in these countries is girded with policies sanctioned by the IMF that keep them dependent on loans to survive, assistance that forces adherence to an austerity regime skewed in the favor of the elite. They starve the public sector and dismantle unions to maintain a low-wage, business-friendly culture that artificially represses growth, requiring ever more assistance. These effects have been evident for generations now, thrust in our faces by the Seattle WTO protests in 1999, but much of the developing globe has still yet to recover from the 2008 downturn, enhancing the difficulty of absorbing its people.

Climate change adds to these problems for the warm, low-altitude border countries bearing the burdens brought by first-world polluters.

The expanding military presence where these policies are imposed or near needed resources like oil deepens the displacement and flow of bodies to our borders, supplementing covert war with the force and disruption that will demand perpetual assistance.

Friedman’s suggestion that foreign aid would help stop the flow of migrants is welcome. This would require huge transfers of funds along with a reversal of IMF policies. Since the bulk of this aid is now in the form of military aid, this would also require a reset of our foreign policy in the direction of diplomacy and infrastructural investment—but what would happen if we funded this investment before doing it here?—to stabilize these countries.

Perhaps, as Suketu Mehta suggests, we should add up the toll for all the ruination imposed on these countries and construct reparations quotas for their entry (New York Times, 6/7/19, “Why Should Immigrants ‘Respect Our Borders’?”). Opening up spaces for the ruined could be sold if we change priorities, starting with a massive infusion of infrastructural investment along the lines of the proposed Green New Deal, paid for with funds from the bloated military budgets. That would correct the problem of underemployment by creating good jobs, and above all reverse the ever-greater reliance on temporary jobs with no benefits begun some forty years ago. Bringing more citizens permanently into the system with higher wages will give them a greater sense of belonging and increase productivity, expand the economy, and open up spaces for more people. The absorption of migrants into these openings should be guided through a partnership between a strengthened labor movement, business and government that jettisons the reliance on un-free markets. Nothing short of this will begin to reduce the blowback from the win-lose logic.

America can lead in the creation of an international order shorn of toxic me-first nationalism.