What a treat to read a new work by Graham Swift! It’s impossible to forget his early novels, especially Waterland (1983), and Last Orders (1996), which won the Booker Prize. Swift is one of those talented writers who doesn’t keep retelling the same story. Each time, it’s something entirely new. His latest, Mothering Sunday, is a gem of a short novel, a novella actually, that you will read in one setting in two or three hours. Such compactness is no easy task, I assure you, ever since the beginning of the computer era when novels became bloated, overwritten, too many of them badly in need of an editor’s pair of scissors. That’s a separate problem, since most editors these days don’t edit. Rather, they acquire. But I digress.

The title is uniquely British, perhaps unfamiliar to American readers: “Mothering Sunday is the fourth Sunday of Lent. Although it’s often called Mothers’ Day it has no connection with the American festival of that name. Traditionally, it was a day when children, mainly daughters, who had gone to work as domestic servants were given a day off to visit their mother and family.” No surprise then that Swift’s novel is set close to a hundred years ago when upper-class British households still relied on a clutch of domestics to help them function. Needless to say, the arrangement was rife with issues of class. Think of Downton Abbey. Can you imagine needing someone to dress you each morning?

he fact is that Jane Fairchild has no mother to visit on March 30, 1924. She was an orphan,  raised in an orphanage, and put out for service as a domestic when she was fourteen. By 1924, when she’s twenty-two years old, she’s been having an affair with a young man, a year older than she, that as been going on for seven years. And, yes, Paul Sheringham is from the upper class, the son of one of the near-by families in the neighborhood where she works. They’ve managed to continue this relationship all those years by meeting in the estate’s outer buildings and never once in a proper bed inside the Sheringham residence.

raised in an orphanage, and put out for service as a domestic when she was fourteen. By 1924, when she’s twenty-two years old, she’s been having an affair with a young man, a year older than she, that as been going on for seven years. And, yes, Paul Sheringham is from the upper class, the son of one of the near-by families in the neighborhood where she works. They’ve managed to continue this relationship all those years by meeting in the estate’s outer buildings and never once in a proper bed inside the Sheringham residence.

But that all changes on Mothering Sunday because Paul is slated to be married in two weeks, to Emma Hobday, and because of the holiday with the servants all away for the day, his family and her family will have lunch together in a restaurant in town. Paul has contributed to the plan but he’s convinced his parents go ahead to the restaurant as he finishes getting dressed. With everyone away, for the first time he is able to bring Jane into his parents’ house, into his bedroom, for a final encounter between the two of them. That means the run of the house, naked, with no one to worry about. Let’s call it freedom, or liberation, even if Jane assumes that this is the last time that she will see him.

There’s a good bit of wonderful space given over to the two lovers’ freedom to finally be themselves in a proper setting. Jane has never seen herself naked in so many mirrors. They’ve never been able to stretch out their lovemaking in such a leisurely fashion. Is this her prize for their final encounter? Even when they are finally getting ready to depart their separate ways, Jane stays naked on the bed, watching Paul getting ready to leave, ever so incrementally, as if he has no need to hurry at all, even though they both know that he will be late for the luncheon with his parents and Emma’s family. Jane can’t help thinking that “It was as if he was dressing for his wedding.” That’s now meticulous he is, putting on his clothes with no urgency for what he has to do next. Furthermore, Paul tells her that she can remain in the house, take a bath, eat some food after he leaves, so Jane takes this as the opportunity to walk all over the mansion from room to room, naked, liberated in a way she has never been before. After all, she is only a domestic.

Then, of course, there is the surprise; something goes wrong, and even though there have been hints slipped into the text that Jane is remembering all the events from that Mothering Sunday day decades later, when she is ninety years old, the jolt is staggering, unsettling because of the hint that Paul knew what was about to happen, that that was why he took Jane into his bedroom, gave her the best moment of their seven-year encounter. Yes, you can argue that he was a bit of a cad, using her as his plaything before he got married, but Jane realizes—at least from her vantage point more than half-a-century later—that he, too, carried around a certain amount of baggage because of the role he was expected to fulfill to please his parents and his fiancée.

Touché for Graham Swift. The issue of class has been central to centuries of British fiction. Mothering Sunday instills it with fresh blood. The novel’s subtitle is “a romance,” and just to make certain we don’t negate that term, the first sentence of the novel begins with these four words: “Once upon a time….”

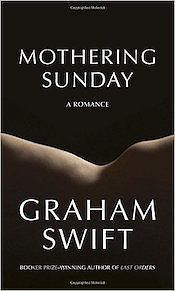

Graham Swift: Mothering Sunday

Knopf, 177 pp., $22.95