Last week I was interviewed on BBC1’s prime time The One Show about Damien Hirst’s plagiarism. Damien Hirst naturally did not accept the invitation to appear, but in the past his reaction to such accusations has ranged from “It’s just gibberish” to “fuck ’em all”.

One would expect nothing less. However, it is somewhat surprising when the same reaction (in somewhat more erudite language) is expressed by the model of cultural establishment, Melvyn Bragg, so esteemed indeed that in 1998 he was raised to the House of Lords as “Baron Bragg, of Wigton in the County of Cumbria”.

The One Show displayed comparisons such as an image of a crucified sheep, exhibited as an artwork in 1987 by John LeKay, and an image of three crucified sheep exhibited as an artwork by Damien Hirst (one time LeKay’s friend) in 2007 (Hirst also exhibited a single crucified sheep in 2005).

The genial, urbane, detached and twinkly-eyed interviewer, Gyles Brandreth, one-time member of Parliament turned entertainer (spot the difference) pointed out in his genial, urbane, detached and twinkly-eyed way that Hirst’s work was in a vitrine of formaldehyde and LeKay’s wasn’t – “He’s presented it slightly differently”.

To this I responded “Hirst himself has said, being a conceptual artist, it’s the idea that counts … It’s a bit like taking an Impressionist painting and putting a different frame round it: you can hardly claim it’s a new artwork.”

“Why, ” Brandreth asked, “is it so important?” My answer was: “We regard artists as embodying worthwhile values – values of integrity, of originality. If the things we’re now looking at Hirst for come from somebody else, we’re looking at the wrong person.”

Lord Bragg does not seem to mind in the slightest if we’re looking at the wrong person. After the pre-recorded item had finished, he was a guest in the studio and, prompted by the studio presenter Matt Baker, nonchalantly proffered what was obviously the most important factor in the whole business: “I’ve made a film about Damien Hirst.”

That is not surprising, as Bragg, the editor and presenter for over 30 years and 800 editions of the TV culture programme, The South Bank Show, has made programmes on most people, including Cher, John Cleese, Liza Minnelli and Barbara Cartland. (I even had a cameo in 2001, interviewed after a Stuckist protest at the unveiling of Rachel Whiteread’s sculpture in Trafalgar Square.)

“Artists always imitate artists,” Bragg uttered suavely, “You look through: they’re imitating each other all the time. That’s what they do.” (Is it? I thought they might do a bit more than that.) “They call it homage. People can call it pinching. They can call it want they want.” (Yes, officer, I was just making a homage to the bank safe.) “The only thing that matters is it’s good at the time…” (really – that’s the only thing that matters?) “..And it hits its own time.”

Then, in full flow, gaining in confidence from his stunning statements to date (I was certainly stunned by them), he launched into a weird and irrelevant tangent that “You can do a self-portrait a thousand years ago and if you tried to imitate that, you’d get nowhere.” (Err?) “But if you did it in a way that meant something now – like Francis Bacon – then it’s a self-portrait or a portrait, and it matters. So they’ve always imitated, artists. People say, ‘I did that first.’ People are always saying they did that first. That’s one of the cries…”

That’s an obfuscation of the objection, which is that Hirst has said he has no shame in stealing, and other artists say they have been stolen from. Bragg’s convoluted and nonsensical argument is the inevitable outcome when, for reasons best known to himself, he chooses to defend the indefensible: the only way he can perpetrate this is through gobbledygook. He is saying that it’s no good just imitating something else (i.e. you have to transform it significantly). But he is also saying the exact oppposite – namely that artists do just imitate all the time.

Another example of Hirst’s “imitative homage” – as we must now call it – aired on the programme was the work of Lori Precious, who had exhibited kaleidoscopic designs made from deceased butterflies a decade before Hirst started making them also from deceased butterflies. Precious was more than a little underwhelmed by his Lordship’s bon mots and emailed me:

“What really pisses me off is that a commentator [Melvyn Bragg] makes it sound like Damien Hirst is swiping work that was done long ago, but not so – he is stealing work of his contemporaries. This commentator says something stupid like an artist long ago may have done work that didn’t hit the mark at the time, but years later another artist does it and hits the mark. While it’s true I did not market my work as well as Damien Hirst (that’s an understatement), it’s not like anyone he stole from is long dead.” Quite.

I wasn’t there in the studio to respond to Bragg, but the London Evening Standard kindly made up for that with a Diary story that quoted Bragg and then my rejoinder that his stance was “contemptible…I doubt if he’d be so smug about it if one of his novels was ripped off and made into a bestseller by someone else before his version got published.”

I was designated by the programme as Hirst’s “most vociferous critic” and while it is true that I have researched various instances of, and been a public voice to draw attention to, Hirst’s plagiaristic – sorry, imitatitively homagistic – practices, it is not any campaign or vendetta against Hirst per se. In fact, when he exhibited his own paintings (that is Hirst paintings painted by Hirst, as opposed to Hirst paintings which Hirst didn’t paint but paid other people to paint), they were slated something rotten, in fact vituperatively, by the critics, and I was virtually alone in extolling him, quite sincerely, as an “excellent painter”.

Whatever my viewpoint, I do make an effort to get my facts right. Bragg seems to have reached the exulted position where he does not need to study reality but has sufficient power and status, and enough acolytes and kowtowers, to exist in the smug delusion that what he imagines to be reality is reality. Thus he smoothly pronounces that “art has changed from ‘Oh, we love that’. It’s an investment for most people. It’s an investment.”

I’m sure there are a fair number who meet exactly that description in the exalted circles where Bragg circulates, but I can’t think of anyone in my life who enters into art acquisition on that basis. I’m not saying they wouldn’t be pleased to find their purchases increasing in value, but their driving motivation to acquire art is the extraordinary reason that they like it and it enhances their life with its meaning and aesthetic appeal.

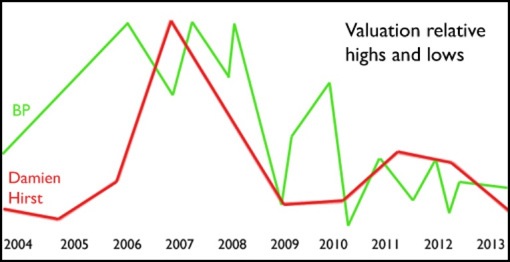

However, Bragg was unstoppable in his theme, imparting with the surety of one who knows: “You don’t buy shares in BP – you buy shares in Damien Hirst. And they’ve done an awful lot better.” The general superiority of art stock over share investment is widely touted – and erroneously so, as Don Thompson, a professor of economics, has damningly demonstrated in his book The $12 Million Stuffed Shark.

Was Bragg, I wondered, continuing to create his own wish-fulfilment reality posing as the all-knowing seer, or had he done his homework? I decided to do mine and created a graph of the relative ups and downs of BP and Hirst values with data from Wikinvest and Artnet. This is an approximation, but clearly contradicts Bragg’s braggadocio. There is really not a lot to choose between the performance of BP and Hirst financially, and if you had bought into either during their high point around 2007, you would not be a happy investor by the time 2013 had arrived.

I didn’t need to do this to convince me that Hirst’s work was not going great guns for (most) financial investors. For some time the papers have carried reports of a glut of Hirst work offered to auction houses, who have lost so much confidence in their ability to reach the right prices, that they have turned work away.

In 2009, the Daily Mail headlined, “As prices for Damien Hirst’s works plummet, pity the credulous saps who spent fortunes on his tosh”, and at the end of 2013, The Independent reported, “auction sales and the average price levels for Hirst’s works have dropped back to 2005 levels. One in three of the 1,700 pieces offered at auction failed to sell at all in 2009.” Works sold a few years ago “have since resold for nearly 30 per cent less than their original purchase price.”

I would not, even considering just purely mercenary reasons, recommend investing in BP or Damien Hirst. Nor would I recommend Baron Bragg of Wigton as either an ethics or a financial consultant.

Charles Thomson is co-founder of the Stuckists art group.

For more info, see www.stuckism.com/Hirst/StoleArt.html