Should the incoming World Bank president, Ajay Banga, be allowed to take office without a full investigation into his predatory-financing history, especially as a visionary leader of MasterCard committed to ‘financial inclusion’?

A great deal can be learned from the past decade’s experiences, beginning in South Africa where he authorized a partnership with a partially World Bank-owned data services firm, Net1. The Bank’s International Finance Corporation bought 22% – the largest single share – in 2016 for $107 million.

Net1’s main subsidiary, Cash Paymaster Services (CPS), was forced into bankruptcy in 2020 after social activism led to judicial prosecution of its long-standing debit-order strategy which impoverished millions under the guise of financial inclusion. Net1 drew poor people into the formal banking system on terms that led to credit-catalysed underdevelopment, not development.

Debt trap for the poor

The world’s most unequal society, South Africa is also one of the world’s most important sites for financial inclusion experimentation first because of its disastrous foray into commercial microcredit in the immediate post-apartheid era. But this lamentable episode was then greatly compounded by the 2010s experiences with the mass collateralization of welfare payments in 2012.

More than 25 million people – of the country’s 60 million residents – today receive a monthly state grant, divided into four categories: unemployment relief for $20, child support for $27, and a grant supporting both the retirement pension and disabled people for $110.

As part of his effort to bank 500 million unbanked poor people across the world, Banga partnered with the South African Social Security Agency (SASSA) and Net1, to use MasterCard debit cards for welfare grant distribution. This new debit card payment system was meant to assist low-income South Africans to avoid long waits at government offices in the hot sun (the source of many deaths of older people), protect them from the petty criminals who stole from grant recipients at paypoints, and diminish the costs of distributing cash, saving the government money.

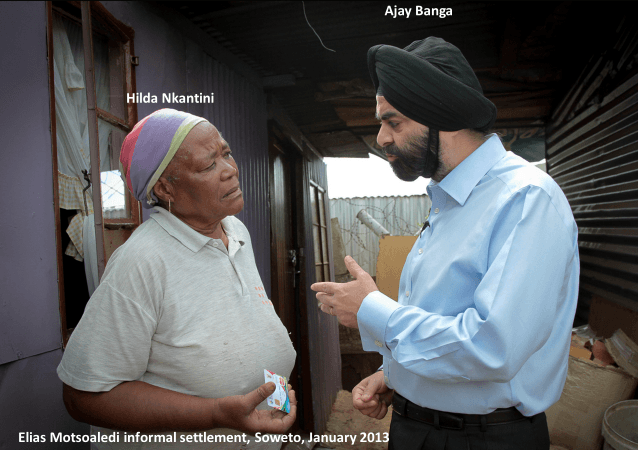

Banga visited South Africa in January 2013 to explore how the system was working, and won over conservative Treasury officials. A more efficient distribution system meant an estimated $80 million in annual savings, Banga claimed.

One of the local leaders he met, Nhlanhla Nene, was South African finance minister in 2014-15 (before he was fired for opposing a dubious Russian nuclear energy deal) and was appointed to the post again in 2018. Nene was soon compelled to resign due to his unexplained visits to the home of the Gupta family, which had corrupted many vital arms of the South African state. The other official Banga met, Ismail Momoniat, has long served in Treasury’s civil service leadership.

One of the local leaders he met, Nhlanhla Nene, was South African finance minister in 2014-15 (before he was fired for opposing a dubious Russian nuclear energy deal) and was appointed to the post again in 2018. Nene was soon compelled to resign due to his unexplained visits to the home of the Gupta family, which had corrupted many vital arms of the South African state. The other official Banga met, Ismail Momoniat, has long served in Treasury’s civil service leadership.

Source: MasterCard on Flickr

Also in January 2013, Banga visited Johannesburg’s sprawling black township of Soweto, and located a recipient in the Elias Motsoaledi shack settlement next to the city’s largest hospital, which MasterCard still features on its Flickr account. Four months later, the Washington Post provided him a puff-piece platform for his recollections about grant recipient Hilda Nkantini:

“In South Africa, I met a woman called Hilda, a 77-year-old lady, living in a little tin shack. And she told me — and it’s tough to keep your head straight when you hear somebody say that to you — she said, ‘Now I feel like I’m somebody. I have a card that has my biometrics. I exist.’ And you cannot imagine the surprise on her face. Getting the same social benefits she was getting earlier, but then it was in cash, and she was anonymous. Now she had an identity inside of South Africa.”

No doubt the new system was greatly appreciated for its convenience. But Banga continued,

“I’m not a philanthropy. I’m not a United Nations agency. I run for shareholders. I have to do well. I believe you can do both… if these guys use their card, I’m going to make money… In the beginning they’ll take out cash at an ATM. I make very little money if they just take out cash at an ATM. But you know what? They’ll benefit by doing that, and that’s the first step.”

From grant access to financial predation

Just at the point Banga claimed he could strike a balance between “doing good” for people and shareholders, South African welfare payments were being transformed into collateral for high-priced financial products. Banga had already begun scaling up MasterCard services by partnering with one of South Africa’s most notorious corporate leaders, Serge Belamant of CPS/Net1.

Through his partnership with SASSA, Belamant was authorized to collect the personal and biometric information of over 18 million South Africans. He was also able to collect a complete history of the income and spending patterns. And he built four subsidiary companies to market financial products exclusively to social welfare recipients, and attach debit orders for new credit-based products (mainly microfinance, funeral insurance and cellphone contracts). Such debit orders often drained grant recipients’ accounts to the point they had little or no incoming funds each month.

Banga repeatedly used Hilda’s story to promote his innovation – here, here, and here – but the main objective of his next-step technology was to facilitate SASSA in its turn to financial predation. SASSA partnered with CPS/Net1, Grindrod Bank and MasterCard to deliver grants at grocery stores, commercial banks, or one of Net1’s 10,000 paypoints (which popped up across the country the first week of every month).

While Banga had rapidly rolled out 10 million cards, Net1 was building subsidiary companies to sell financial inclusion products to grantees, including loans (Moneyline), insurance (Smartlife), airtime and electricity (uManje Mobile) and payments (EasyPay).

As a monopoly service provider, Net1 controlled the entire grant payment stream from the state Treasury to recipients. It was well positioned to not only transfer the grant payments, but to sell financial products and extract repayments at the same time as grant payments were made.

There was no possibility for grantees to default on their debts because repayments were deducted automatically, and no longer depended on consumer behavior. As repayments to Net1 whittled away the promised value of social entitlements, grantees turned to other formal and informal lenders, many of whom were also repaid automatically through Net1’s same debit-order powers.

While Net1 claimed to offer credit without interest, their monthly “service fees” were typically over 5% interest per month. Though technically allowable under the National Credit Act, these interest rates amounted to over 30% on a standard 6-month loan. At the time, interest rates on a credit card were slightly over 20% per year. Through their high-priced credit, Net1 gained more income from financial inclusion products than from the distribution of social grants from 2015-17.

While it is difficult to estimate the cost to grantees – because this information was controlled by Net1 – there are some useful proxies. The well-known welfare-advocacy NGO Black Sash conducted a survey between October and November 2016, and out of 1591 grantees, 25.5% answered ‘‘yes” to the question: ‘‘was any money deducted from your grant without your consent?”

The partnership between Mastercard and Net1 was novel because they created a debit card that ran two parallel payment systems: Europay-MasterCard-Visa and the Universal Electronic Payment System (UEPS). The former worked online with a PIN number as it does throughout the world; the latter worked offline with biometric security and was specifically designed for South African grantees.

The implication of this dual system was that the vast majority of transactions by social grant recipients were through the offline UEPS system, either at Net1 paypoints or retailers using Net1 point of sale devices. Instead of these transactions being settled through the National Payment System, thereby becoming visible to the country’s Treasury and Reserve Bank, they were settled internally by Net1.

Most of these deductions for Net1 products happened outside traditional financial structures. This led to significant financial predation by a monopoly service provider.

In short, facilitated by MasterCard, Net1 developed a shadow banking system that did not, in reality, introduce grantees to the mainstream financial sector but instead segregated them in a monopolistic digital payment space outside of state oversight and control. Net1 controlled the distribution stream from the Treasury to recipient accounts, and could therefore deduct payments for financial products from grants just at the moment that state money was transferred into their bank accounts.

Grant recipients could not choose whether to pay or delay, as repayments were deducted automatically. The SASSA-MasterCard-CPS/Net1-Grindrod partnership eliminated nearly all risk of default, using the social welfare state as a guarantor for private credit. The desperate situation for millions of grant recipients who fell into a predatory relationship via MasterCard was then compounded by concerns the welfare minister had herself been corrupted in the process.

This in turn led Black Sash to investigate and litigate against CPS. By September 2020 they were successful, and had not only ensured Net1’s contract would not be renewed but won a reparations demand that forced CPS into formal bankruptcy (although Net1 continues to play a welfare payments distribution role in South Africa and several other countries).

South Africa and Brazil as poverty-collateralization pilots

This kind of de-risking strategy turned welfare benefits, underwritten by the state, into a new form of collateral, reversing the very purpose of anti-poverty cash transfers, i.e., alleviating their levels of deprivation through monetized poverty relief. Similar processes have been underway in Brazil and many other sites of cash transfer systems.

The World Bank had been deeply skeptical, and indeed openly opposed to any kind of monetary transfers to the poor until the late 1990s (on the grounds that they would exacerbate poor people’s destructive consumption habits). But having envisaged the ease of debt-loading a regular income stream, began championing the scheme as the new social policy blueprint for the Global South starting in the early 2000s.

Conditionalities were adopted and strict eligibility criteria were established to legitimize the use of state-sponsored cash transfers, thus introducing parameters – such as means testing and workfare requirements – that discriminated the poor into the classic division of ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving.’ Soon the deserving poor became the centerpiece of the financial inclusion strategy that the World Bank set out to pioneer in close association with large financial corporations.

Today, billions of poor households have become, at the same time, cash transfer recipients and bank account holders. This has opened up not only the possibility of taking out loans – which is considered a new form of social ‘right’ in the wake of the supposed microfinance empowerment wave – but also to a new existential condition: structural indebtedness.

This means that a new, even more perverse and abject form of poverty is emerging, one that occurs through the financial extraction of those most vulnerable, who now need to permanently resort to ever higher debt levels to repay old loans and make ends meet. Throughout the poorest countries, as well as middle-income economies such as South Africa and Brazil, extremely high indebtedness of the working poor and the most disadvantaged has become an alarming social issue, requiring even the development of target programs that can help these huge contingents of debtors to renegotiate their payments, and thus their ability to live in debt.

This shows how dramatic the Bank’s presidential appointment of Banga will be, even more so now that tackling the climate crisis urgently calls for a new generation of eco-social policies that truly and equitably meet the needs of those who continue to pay – in the Global South – for the mistakes of failed development policies and the Global North’s overconsumption of greenhouse gases.

In pursuing financial inclusion along these lines, MasterCard is one of an elite group of digital payment, telecom and financial corporations, digital utopian philanthrocapitalists (notably the Gates Foundation), innovators like Belamant, right-wing lobbying organisations, allied NGOs like Accion, and the World Bank and IMF. This elite group has been termed by Daniela Gabor and Sally Brooks the ‘fintech-philanthropy-development complex.’

Their central claim is that if provided with greater access to a set of digitalised microfinancial services (small loans, savings opportunities, money transfer payments and technology, debit orders, etc) delivered by for-profit investor-driven fintech platforms, the poor in the Global South will be better able to escape their poverty.

Fintech fantasies

However, the evidence to back up this heady contention is very weak. For a start, much wider access to such services has already been achieved since 1990 thanks to the microfinance revolution and widespread debit-card issuance. Yet even one-time leading advocates now accept that the supposed revolution ultimately had zero impact on global poverty.

Moreover, early fintech platforms that were once widely claimed to be excellent ‘role models’, notably Kenya’s M-Pesa, have ‘matured’ in a destructive manner, and now increasingly exploit their clients.

We must therefore be extremely wary of the excited claims being made by those wanting to expand fintech services, as their motives are much more about advancing their own financial interests and promoting a particular ideological worldview, than addressing structural economic injustice.

The MasterCard Corporation is a good example. Its well-publicised corporate goal of wanting to extend financial inclusion in order to address global poverty allegedly reflects the corporation’s high level of social responsibility, as well as Banga’s passionate personal interest in linking technology to development.

But neither of these accounts add up in practice. Even leading CEOs in the fintech sector, such as PayPal’s Dan Schulman, now readily concede that financial inclusion is simply a euphemistic ‘buzzword’ for recruiting as many new clients as possible, the better to be able to quietly extract a never-ending stream of value from intermediating their trillions of dollars’ worth of tiny financial transactions.

And as the example of CPS/Net1 in South Africa manifestly demonstrates, the real beneficiaries of this form of investor-driven fintech are not the clients in poverty, but the fintech CEOs, their shareholders and investors and, ultimately, the economies of the Global North, in which their operations are typically headquartered.

For these reasons, Banga’s accomplishments appear as a repeat version of the earlier colonial adventures that allowed the great powers to wreak havoc upon their subjects. By extracting enormous natural-resource and labor-based wealth under cover of the ‘white man’s burden,’ or spreading Christianity, colonies were programmatically plundered and under-developed.

Today a similar extraction exercise is underway, justified now under the banner of extending financial inclusion via a ‘Fourth Industrial Revolution’ combining consumption-based algorithms with card technology. So whether by design or default, Banga’s appointment is likely to advance the US government’s strategic goal of promoting Western consumption norms and indebtedness via the spread of fintech platforms owned and controlled by US corporations and US investors. Banga has shown how these operate to benefit the US economy, while undermining the financial guinea pigs and the broader economies of the Global South.

Nkantini didn’t fit MasterCard’s script

Upon hearing of Banga’s new job, we were curious whether Hilda Nkantini had suffered from his decade-long financial predation in South Africa – and learned that her financial common sense had prevailed over MasterCard’s poster-child marketing and the fintech-philanthropy-development complex’s gimmicks. If you track her down to the same impoverished shack settlement where she has resided for decades – as did University of Johannesburg Centre for Sociological Research and Practice scholar-activist Siphiwe Mbatha last month – you learn that she barely survives, economically.

But while she still gratefully uses her MasterCard, she was insistent that she never took advantage of debit orders placed against her grant for spurious services and loans.

Back in 2013, the Post reporter asked Banga only one tough question about his South African project: “Does this also allow MasterCard to collect data for marketing purposes? And what about privacy concerns?” His answer evaded the reality behind the deal MasterCard made with Belamant: “Not really. Remember, basically as an operating system, I don’t really get information by an individual’s name. This will all go to the government.”

Hilda Nkantini provides proof that the neoliberal agenda associated with seductive financial inclusion can be resisted. Nkantini appreciates technological advances (the card-based distribution of grants) but doesn’t fall for biometric surveillance or debit-order collaterialization of welfare-sourced income.

That subtle resistance, a jujitsu of Banga’s ideology and the CPS/Net1 partnership, was all too rare, however. As a result, the predatory features of MasterCard’s abuse of grant distribution are the main legacy Banga left in South Africa.

Moreover, the World Bank’s fingerprints on the abuse were confirmed when in mid-2021, its 2022-26 South Africa Country Partnership Framework assessment of the 2010s financial inclusion deal proudly declared that its objectives were ‘mostly achieved.’ Under the heading ‘Lessons,’ the section containing Net1 was left blank.

In that sense, Ajay Banga is the perfect man to lead the World Bank, since its historic role has been largely predatory and since mass poverty creation has regularly occurred through its pro-corporate ‘development’ projects and macroeconomic structural adjustment programs. Add now to this, the financial inclusion rhetoric that runs from 1990s microfinance to Banga’s recent collateralization of poor people’s welfare grants. The next five or ten years that Banga will run the institution are sure to confirm the impossibility of its reform.