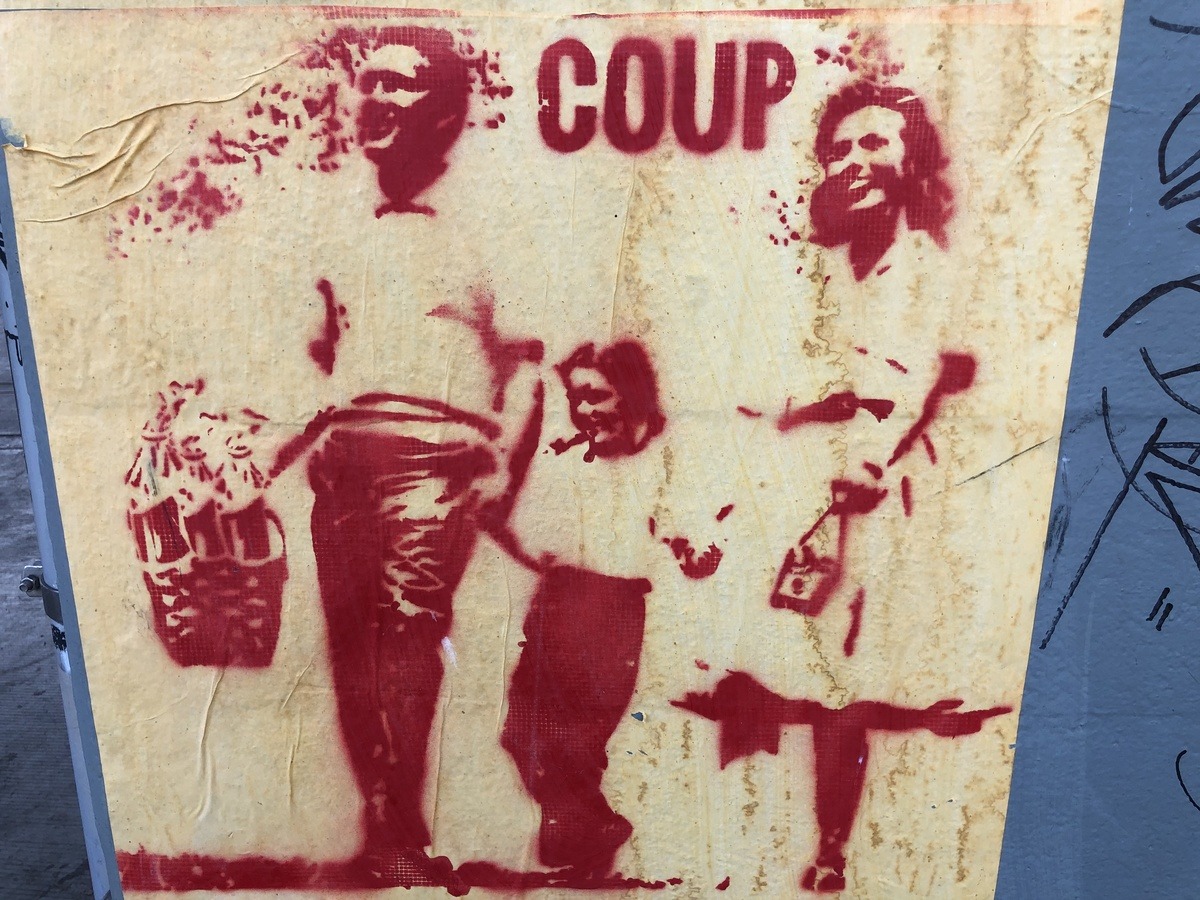

Photograph by Nathaniel St. Clair

In the recently released The Sinking Middle Class: A Political History, David Roediger floats the Marxist-driven notion that the American Middle Class is a misery-filled achievement, producing more Bartleby the Scriveners than East up-moving Jeffersons, and is not worth saving. He explores the language of classification and definition used by politicians and the media to promote the false mythos of achievement striation – falsified by the slippery slope of capitalist expendability, and the Sisyphean struggle to maintain a level at great expense to long-term well-being.

Roediger demonstrates that the term Middle Class is not an original designation of the American caste system, but of recent vintage. He writes, “Put forward first by the Democrats, it has debased how we understand social divisions in the United States and sidelined meaningful discussions of justice in both class and racial terms.” Bill Clinton was the first to blur the lines between white working class and middle class, he argues, “by standing ever ready to hear white suburban angst regarding affirmative action, welfare, and crime, fashioning flirtations with racism and vague appeals to ‘economic’ issues as a populism of society’s white middle.” He suggests an inevitability to the rise of a Trump out of this manipulation.

Obama appointed Joe Biden to head up his Middle Class Task Force and did little with its implied authority. Biden got a free ride this election cycle when the issues were reduced for Democrats to getting Trump out of office at any cost (including electing someone as weak as Biden) and dealing with the Corona pandemic. Biden has come out post-election, not talking about the “Middle Class” and its needs, or of much-needed economic redistribution, but of the uniting fight against the common terror of the pandemic. He’ll be there when the vaccines come out and he can play the hero, distributing shots the way Trump did paper towels. Whether “Middle Class Joe” ever shows up is anyone’s guess.

Roediger sparks a vision of democratic socialism and invites the reader in for that conversation. It may be a talk that Democrats don’t want to have, any more than Republicans, even if both chambers of Congress end up with Democrat majorities as Biden begins his term as president (Obama wasted a similar opportunity in 2009). And Biden may not want to reveal the corporate quid pro quo understandings that paid for his way to the presidency. But Roediger suggests that Corona may hasten the changes required to address long-suffered economic and social inequities, whether anyone is ready for them or not. You can’t con a virus.

Roediger teaches American Studies at the University of Kansas. He has a long history of critical thinking and compelling articulation about race and class politics in America. His previous studies include Seizing Freedom: Slave Emancipation and Liberty for All and The Wages of Whiteness: Race and the Making of the American Working Class. More information can be had at David Roediger’s website.

The following is a recent post-election interview with Roediger:

In The Sinking Middle Class, you state:

Elections now rarely seem anything but imminent and historic. We heard in 2018 of the most important election of our lifetime. As soon as it was over candidates announced for the infinitely more important 2020 presidential vote.

Was the 2020 election more historic and important than usual? Why or why not?

It was unquestionably an important election, a defeat for white nationalism and for Donald Trump’s authoritarianism. It returns us to a more familiar pattern of less-than-functional US politics in which Democrats will administer neoliberal rule, albeit with a voting base that is Black, Indigenous, and Latina/o and or sympathetic to socialism in its near majority. If social movements can energize the demands of those groups the 2020 election might end being seen as important beyond the fact of what it prevented.

Recently I read a book, Has China Won? by Kishore Mahbubani, which, among many things, argues that if China can induce other countries, especially in Europe, to move away from the Dollar, then it could prove catastrophic for the American middle class, which he suggests is, as you say, built on illusion. Any thoughts on such a strategy and its consequences?

The specifics here far exceed my expertise but the question does verge on an issue I regard as critical and ignored. That is the relationship between the unravelling of the US political system and the decline of the US as the hegemonic leader in the world economy. Trump’s instability and isolation is usually read as peculiar to him and to the far right and perhaps as something destined to disappear with his loss and ultimate discrediting. But what if the decline of the US economy in world importance has left it one empire among several rival ones, unable to police and direct a world system but clinging desperately to the illusion that it can do so. The wild swings between petulant threats and America First disinterest in global institutions that Trump presented fit his own pathologies and attention span but we are likely to see them again, and in both parties. The death wish politics associated with COVID and masks in the US also fit well with end-of-imperial-domination desperation.

How would you “define” the middle class in America today? Are we all becoming ‘deplorables’?

In The Sinking Middle Class I argue that the idea that the US is a “middle class society” has thrived over the last 90 years because it has meant so many different things. Middle class is a term of self-identification through which people of all sorts of different levels of wealth and various relations with management imagine themselves as having something in common. Many people with working class jobs choose to identify as middle class, though less so in recent years. Cold War ideology and electoral political appeals have encouraged such identifications immeasurably, promising respect and attention to those claiming middle class status. (Also encouraged, tragically, is a “white working class” identity.) On the other hand, middle class is at other times defined by experts (below $250,000 in annual income, presidential advisers often argue, or college-educated, or those within a certain percentage of median wealth, for example). Self-identification, if data collectors offer working class as an additional choice, does in this period yield useful information. As for “deplorables,” the pandemic response so far seems more eager to cast us as “expendables” instead.

How did Trumpism play into the slippage of the great buffer zone between the poor and the ultra-rich?

The loss of relative wealth to the top 10% (and especially the top 1%) by the rest of those in the US has been thoroughly bipartisan in the sense that it has proceeded during administrations of both Democrats and Republicans. Trump tax policies certainly favored the very rich. The loss of relative wealth by those in the middle of the social structure helps account for many of the MAKE AMERICA GREAT AGAIN hats that we see in the US.

In your book, you discuss Macomb County as a kind of litmus test for “progressive” politics. Greenberg and company would be brought in to influence voters by way of study groups and the like. Macomb and the whole “progressive” movement seemed to be irrelevant this time around. There were few promises of anything from the Democrats, other than getting Trump out. Will we regress to progressive policy promises now that Biden’s calling the shots?

For what it’s worth, Macomb County went for Trump by about 8 percentage points in 2020 but Biden won the state of Michigan, proving the county once again to not predict electoral success. The secret of appeals to its importance lie instead in their enabling center-right Democrats (confusingly adopting the mantle of “progressive”) to profess the centrality of white working people to campaigns without providing substantive programs empowering workers or their unions. Joe Biden is very much part of this center-right wing of the Democrats and seems likely to continue such a tradition. The Democratic platform does include planks on green politics, labor law reform, and racial justice—it long has included progressive language—but the lack of a strong majority legislatively and the professed desire to govern in concert with the Republicans argue against expecting much.

A central thesis of your book is that the Middle Class should be allowed to fail — essentially, you argue, because it’s already a failure as a class to aspire to. Middle Class life seems almost Dickensian in its misery. Can you say more on that?

So many of the appeals to “”save the middle class” in the US assume that if the decline could somehow be halted, and a little material prosperity returned, all would be well. One contribution of The Sinking Middle Class is to retrieve something of the critique of the conformity and consumerism of the middle class and of the miseries of white collar labor that was so much a part of US culture—think Herman Melville’s “Bartleby” or Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman—before the Cold War insisted on a strong middle class as a unique achievement of US “free enterprise.” The levels of debt, uncertainties of jobs, hours of labor, and management of the looks and personalities of office and sales workers make it clear that being middle class is a plight and not just a perch.

Do you believe the Covid-19 pandemic will hasten the demise of the sinking Middle?

I think so but in complicated ways. So far, those who can work remotely have more success at continuing work and staying safe. To some extent that tracks tech, white collar, and academic jobs. However, the vulnerability of all is manifest and university employers, for example, are seizing this as a way to further cut jobs, perhaps then hiring people back for less and having them work from home. The dwindling number of people considering themselves middle class by virtue of having a good unionized job will face great precarity in a climate of post-COVID austerity. Many laid off middle class workers are losing their insurance at the worst possible moment.

Now that Bernie’s “radical” democratic socialism solution has been pushed back successfully, what is the future for Left “progressive” politics?

The euphoria of beating Trump is real but when the dust settles the costs will be apparent as well. In the end almost all of the 150 million votes went to a candidate, whether Trump or Biden, who explicitly campaigned against the Green New Deal and Medicare for All and who favored fracking and funding the police. Without a Trump to vanquish, perhaps some in the left will welcome the question whether the payoffs of electoral politics at the national level justify the immense amount of money, time, and energy invested.

Will ‘Middle Class Joe’ come through?

The “Middle Class Joe” label was very much a self-anointing by Biden and his campaign. His camp briefly held that everyone called him that but reporters could find hardly anyone who did. He has represented well perhaps the most corporate-dominated state in the US for many decades. To the extent that a divided Congress permits him to deliver for any of his supporters it is more likely to be with policies benefitting his largest donors than with delivering for the average Democratic voter.