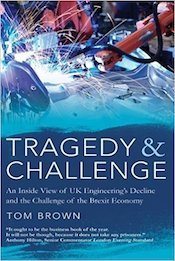

Tom Brown’s Tragedy and Challenge: an Inside View of UK Engineering’s Decline and the Challenge of the Brexit Economy is an absolutely splendid book, full of ideas about how Britain can succeed as an independent country. Tom Brown worked in engineering businesses for his entire 45-year career. Throughout the book he stresses the vital importance of a thriving manufacturing sector, especially the key engineering sector.

Manufacturing is still significant. The UK’s manufacturing output rose by nearly 50 per cent in real terms from 1970 to 2000. From 1994 to 2014 productivity rose by 60 per cent, 2.9 per cent a year. But manufacturing’s share of our GDP fell from 27 per cent to 10.6 per cent and its share of jobs fell from 29 per cent to 10 per cent. Our manufacturing output in 2016 was still 6 per cent below what it was in 2007. And crashes in manufacturing have happened all too often – 1975, 1980-81, 1991, 2002, 2009 – on average every 8 years.

Unfortunately he argues for sour staying in the EU’s single market and customs union. But we don’t have to be in the single market to have access to the single market. Access to the single market is not granted or withheld by the EU, but is available to all nations. Japan, for example, is not in the single market yet exported 66 billion euros’ worth of goods to the EU last year.

His key argument against our leaving the EU’s customs union is that this would add an extra day to logistics. No – almost all customs declarations are now received electronically and can be lodged before goods arrive. The World Bank Logistics Performance Index for fifteen developed countries showed that in 2016 98 per cent of all goods were cleared without physical inspection and the median clearance time of the other 2 per cent was one day – most within a few hours.

Britain already runs one of the world’s most efficient customs systems. In 2016, the World Bank ranked us fifth in the world on customs performance.

He notes that the main problem has been and still is bank debt, the vast bulk of which is not for new investment but for buying existing assets, particularly private houses. Loans for real investment projects actually fell as a proportion of GDP from 14 per cent in 1987 to 11 per cent in 2009.

Three quarters of 2009 bank lending was to private individuals, 12 per cent for personal consumption and 64 per cent for residential mortgages. Household loans soared from 14 per cent of GDP in 1964 to more than 90 per cent in 2009. Putting so much cash into a largely static housing pool, not any shortage of new building, forced up house prices.

He stresses the damage that the banks are doing: “While the government’s abdication of control of much of the economy to the banking sector has been the core of the problem, contrary to much popular belief UK government borrowing itself was not a really serious problem until the 2008 recession hit.” As he points out, “the one thing Germans don’t invest in is financial engineering, debt, derivatives, and takeovers! Unfortunately we have usually done vice versa.”

As he writes, “all too often ‘the market’ in practice becomes ‘the City’, what they will finance and what strategies and managements  they will back, multiplying the power over UK society of a very small group of extremely highly paid Londoners whose only motivation is their own short-term profit …”

they will back, multiplying the power over UK society of a very small group of extremely highly paid Londoners whose only motivation is their own short-term profit …”

In pensions, insurance, unit trusts and similar financial institutions, fund managers make the investment decisions: “publicly quoted companies in the UK come under immense short-termist pressure from fund managers not to invest in capital expenditure, or R&D, or training, but to maximise RONA [return on net assets], profits and free cash flow, to the very short-term benefit of shareholders through a higher share price, increased dividends, and share buybacks.”

Most fund managers see capital investment as a drain on resources rather than as an opportunity for profitable growth. In particular, Private Equity houses “invest almost nothing in longer-term projects, for example product development, process technology, R&D, and training, as these reduce short-term profit and cash and are unlikely to assist their all-important exit valuation.” In 2014 members of the British Private Equity & Venture Capital Association ‘invested’ £4.3 billion in the UK, almost all buying existing assets. Only £0.3 billion was venture capital.

So “UK dividend distributions are higher than in most other countries, even America – fund managers here prefer to have cash paid out to them rather than reinvested in the company, and consequently UK quoted companies are pressurised to pay high dividends and sustain them even in the face of recession.”

He notes that “Fund managers tend to love M&A (mergers and acquisitions) … although statistically most acquisitions fail to achieve the expected benefits; the winners are the acquiring executives, the selling shareholders, and as ever both sides’ ‘advisors’, while the acquiring shareholders and acquired people are the losers. … the UK’s exceptionally high level of M&A activity benefits the banks through the enormous fees generated but is detrimental to most businesses and to society more generally.”

Most fund managers profit more than their investors. The Financial Conduct Authority found that these funds provided poor value for money and cartelised rather than competing. Most funds destroyed value; their services cost more than the value they added.

The average hedge fund returned just 3.27 per cent a year over the last five years, while a very low-risk tracker of the world’s largest companies returned 8.3 per cent. In 2014 the average hedge fund returned only 3 per cent to its investors while the top 25 individual managers got $11.26 billion, an average of $450 million a year each.

He sums up: “Overall the City has made an extremely negative impact on quoted engineering companies, particularly through short-term pressure for profit at the expense of investment in people, technology, and marketing, and by promoting unfocused takeovers, and encouraging debt. In striving so hard to create instant wealth, it inhibits its creation.” So “the City became extremely unscrupulous, unethical, uncaring, and plain illegal on a very big scale.”

His remedy? “I would … end fractional reserve banking, instead adopting the so-called ‘Chicago Plan’ – preventing the banks from manufacturing debt. This would not only greatly reduce the amount of debt, the root cause of so very many of our business and also social problems, but would have the further benefit of greatly reducing the totally disproportionate and unprecedented size, profitability and power of the financial sector in the modern economy. Overall it would greatly increase stability, and much reduce the risk of further crises. … The government also needs to be much tougher in controlling criminal aspects of the City, such as insider trading and LIBOR rigging, and also reforming the pay and bonus culture. … The government must … ensure the banking reforms are sufficiently rigorous, with criminal prosecutions for offenders …”

As he points out, foreign ownership now accounts for half our national engineering output. Back in 1973 foreign-owned companies produced only 15 per cent of manufacturing value added. Overseas acquisitions of UK companies are classified as inward investment – “so we record selling the UK to foreigners as ‘investment’. … We are completely open to takeovers by foreign companies, apparently the most open country in the world. … the acquisition of UK companies by foreign ones is negative for us. IP [intellectual property] tends to migrate away; 39% of UK patents are controlled by foreign companies, compared to 14% in the rest of the EU and 12% in America. Marketing and selling and product development tend to be organised globally by multinationals and so they too often move away. The UK company becomes stripped to just a manufacturing base, which reduces it to competing on cost. It is then vulnerable to closure decisions taken far away, and so in due course manufacturing tends to migrate too, especially since the UK is one of the easiest and cheapest places to make employees redundant – so when volumes decline, overseas owners close their UK works and protect their domestic employees. … Meanwhile dividends of course flow to overseas owners, in some cases even more than the profits earned if the owners gear the company up with debt. In 2014 earnings accruing to foreigners investing in the UK rose to £25b.”

“Overall then, companies coming under foreign ownership generally contribute less to the UK economy and society than domestically owned operations, and very importantly we lose control of our destiny. Apart from engineering, much UK infrastructure is also now under overseas control – including conventional and nuclear power generation, ports, airports, and water supply, which doesn’t seem strategically at all sensible. Other advanced countries simply block unwelcome overseas acquisitions, for example Germany, France, Canada, Japan, and even the USA …”

In 2014 the average UK worker worked 22 per cent more hours that the average German worker. 27 per cent are working part-time, many for fewer hours than they wish – this is underemployment. 22 per cent of jobs require only the educational level of an 11-year-old. 40 per cent of York University graduates ended up doing jobs that did not need degrees to do. Self-employment – almost entirely in services – is also often underemployment.

Productivity and pay are far higher in manufacturing than in services. No engineering jobs are on the minimum wage or zero hours contracts.

The OECD found that 2.3 million higher-skilled jobs were created in 2012. So were 2 million jobs requiring the least skill, while 1.2 million jobs were lost from the middle.

The Institute of Public Policy Research found that 94,000 people trained in Beauty and Hair in 2011-12, for just 18,000 jobs, while 123,000 trained for engineering and construction for 275,000 jobs.

Brown writes, “The ‘Northern Powerhouse’ is just a phrase, and it is hard to believe that devolution in England will achieve more than a further layer of bureaucracy. There is wide agreement on the need for North-South rebalancing, but I believe the fundamental key to achieving this is the recovery of manufacturing.”

But governments here have seen engineering as just ‘metal bashing’. When the author asked Labour’s Ed Balls, when he was Chief Economic Advisor to the Treasury, his view on the decline of engineering, Balls replied, “You might as well mourn for the dinosaurs.”

Brown ends with recommendations for accessing the single market, industrial policy, economic management, energy policy, education, taxation, fund management, corporate governance, private equity, representation and accountancy. His key recommendations are these:

In industrial policy “Choose engineering as a sector to back. Consider import substitution and rebuilding supply chains, and support for exporters. … Conduct tougher public interest reviews of overseas takeovers. Change the restrictive terms of the Business Bank, establish an engineering investment fund …”

In energy policy “Establish and implement a clear and effective policy embracing cost and security of supply, with protection of the environment. … Bring fracking under the control of one unified authority, and mitigate the impact on the environment and local communities.” He notes that “Thatcher “went on to privatise utilities that did not operate in freely competitive markets and where long-term consideration of the national strategic interest is crucial, for example energy and the railways. In these instances it has worked very much less well, and there is a strong need for reconsideration.”

And in education “Invest more in primary and secondary schooling, while pruning tertiary colleges and greatly promoting vocational training. … Improve funding for technical subjects in universities, and increase their contacts with engineering industry. Introduce a prestigious engineering qualification. Remove private schools’ charitable status, and provide state schooling on the same basis for all children, with no faith or grammar schools. …”