Quentin Crisp, the late gay icon or, as he put it, “one of the stately homos of England,” was the embodiment of the English teacher’s maxim, “Write what you know.” Bursting onto the scene with The Naked Civil Servant, which recounts his youth during the violently homophobic thirties and forties, he spent most of his career writing about himself.

Volume 2 of his trilogical autobiography, How to Become a Virgin, describes his life after he moved to New York at the age of 72. (The way to become a virgin, in case you’re wondering, is to appear on television. “All your sins will be forgiven,” he promises. He meant, by the public, of course; those very people who had been making his life so difficult up until that moment.)

However, it was not merely his story which seized one’s attention (he was “out” long before that became a thing;) he was at least as well known for his style.

How could a man who owned only two suits and four shirts have achieved prominence in such an unlikely area of expertise?

Partly it was his unabashed self-assurance. “To thine own self be true,” he seemed to proclaim by his very being, “even when that self flies in the face of every accepted norm.”

But even more, it was the style of his writing and conversation which accounted for his popularity far beyond the niche market of gay male culture. He not only walked the walk; he also talked the talk, and better than anyone else. On paper, as in his one-man shows, the quintessential quips popped out, making him a popular dinner guest – (he was listed in the phone book) – including by my mother, after I sent him a fan letter and he replied, enclosing his home phone number.

Not since Oscar Wilde had man and style been more intimately fused. Even when a stranger called to threaten his life, he responded with the aplomb of the Queen herself, ”Would you like an appointment?”

In keeping with his role as guru, he explains how to achieve such originality: “[I]f you describe things as better than they are, you are considered to be romantic; if you describe things as worse than they are, you are called a realist; and if you describe things exactly as they are, you are called a satirist.”

However, although he plumbed his own experience for material which he then presented with a unique twist on honesty, he was not introspective in the way that readers of memoir have come to expect in our tell-all era. Crisp was a man of his time as well as of his country of origin, both of which furnished his ever-so-polite, velvet-glove-concealing-poison-tipped-stiletto style. The self to which he was true was not a person so much as a persona; a fascinating one, to be sure, made only more alluring, like Miss Garbo, as he called her, by its essential elusiveness. But anyone wondering where the real human being lay beneath the performance he maintained even in private conversation, knew better than to pry.

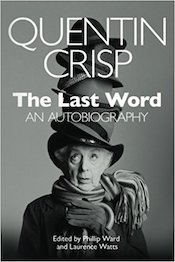

This state of affairs is set to change with the publication of Volume 3 of his autobiography, The Last Word, on November 21, the 18th anniversary of his death.

The book has taken so long to arrive at this point, Phillip Ward, Crisp’s best friend and the executor of his estate explains in the moving Afterword, because of the exigencies of settling Crisp’s affairs (Crisp famously never cleaned, asserting that after the first four years, the dust doesn’t get any worse; a claim which, Ward reports, turned out not to be true) and get over the loss. To prepare the work for publication, he enlisted the support of Pink News features editor Laurence Watts, who provides the enlightening Foreword.

Crisp’s hallmark wit is still very much alive. An accountant is compared to “a vast hamster, living in a nest of shredded paper.” The verbal conjurer is even  generous enough to let us in on how it’s done: “People say that brevity is the soul of wit but brevity is, in fact, the body of wit. The soul of wit is truth.”

generous enough to let us in on how it’s done: “People say that brevity is the soul of wit but brevity is, in fact, the body of wit. The soul of wit is truth.”

But for the most part, the book is written in a more simple, direct style than we had come to expect from him. It’s also the only book that he wrote of his own volition rather than on demand.

Fans of quintessential Queen Quentin may be disappointed to meet Quentin sans the trappings. Straight men will probably not be interested in the details of his cooking on a hot plate and doing nothing on Sunday. But gay men and women of either persuasion are likely to appreciate being invited into his life off stage. I, for one, found The Last Word a revelation as wonderful as that of Joan Didion’s The Year of Magical Thinking, following the death of her husband and sometime collaborator, John Gregory Dunne; as necessary to closing the circle of Crisp’s oeuvre as the last shot of Citizen Kane when the camera zooms in on the logo of the eponymous character’s childhood sled: Rosebud.

Crisp’s version of Rosebud will not come as much of a surprise to anyone familiar with his life: His great regret lay in his not having been born a woman. Although he’d gone through life thinking of himself as homosexual, he learned at the end that he was actually transgender.

Not that he longed to play the female sexual role. Like many women, he maintains, he wished only to be admired. But he also understood the rules of the game as expressed by “Ms. Dietrich:” “You have to let them put it in, or they don’t come back.”

With hindsight I would have been happier being celibate in a monastery than in degrading myself before strangers as I did. I thought it would bring people to me and that they would like me and they would be happy, but, of course, they despised me because their interaction with me made them ashamed.

Apart from the initial “error” on Nature’s part in assigning him a gender, the deprivations of his early years are not probed. We learn that he hated his father (as did everyone else in the family, according to his mother) who he believes hated him first, for adding another mouth to feed to an already strained household. There seems to have been no overt, physical abuse; simply a sense of being resented and of returning the favor. But we’re given no further details on the deep hostility that prevailed in the family, providing the springboard for Crisp’s escape into what he describes as a daydream that would last his entire life. In fact, the only account of an emotion concerns people he’s never met:

A woman once wrote to me and sent me a copy of The Naked Civil Servant and said, “Will you sign this for my son’s birthday? His name is William. He came out to me and I am trying to support him as much as possible.” Well, I ended up losing her address and it made me unconscionably sad.

It’s enough, however. And I fervently hope that William and his mother stumble across this beautiful book.