Tale of Two Artworks

On March 11, 2021, I bought an etching by Francisco Goya for $500 on eBay. On the same day, two people with the pseudonyms Metakovan and Twobadour bought a Non Fungible Token by Mike Winkelmann (pseud. “Beeple”) for an astonishing $69 million at an online Christies auction. An NFT is a digital token representing the unique version of something, in this case a work of art.

The Goya print (illustrated above) is titled “Truth Has Died” and the NFT (illustrated below) is titled (redundantly) Everydays: The First 5,000 Days.

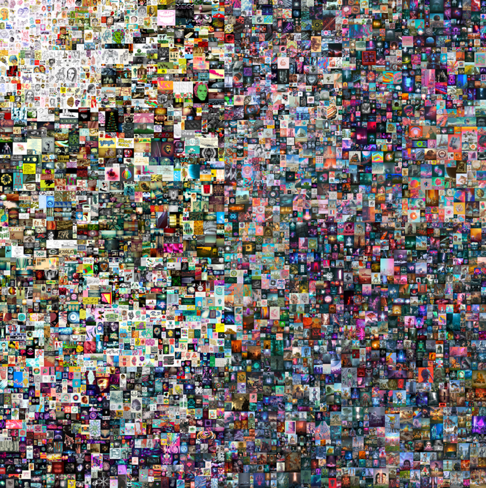

Beeple, Everydays: The First 5,000 Days.

It’s tempting to say the two sales are the product of completely different art markets, one catering to relatively low wealth individuals (that’s me), and the other to millionaires and billionaires. In fact, there’s just a single art market; what moves one, moves the other. And it’s the masters of financialized capitalism who pull the strings.

Goya

Francisco Goya (1746-1828) is famous. His work is in most major European and American art museums, most notably the Prado in Madrid. There you’ll find, among many other of his paintings, the Third of May, 1808 (1814), which documents Napoleon’s reprisals against the Spanish pueblo for their resistance to invasion.

Francisco Goya, Executions of the Third of May, 1808, 1814.

It represents more than that, however. By illustrating the bloody sacrifices of the people, Goya is saying that the previous six years of war were worth it: the monarchy was restored and Spain’s “ser auténtico” (authentic essence) was protected. The paintings were obvious efforts by the artist to get back into the good graces of the Spanish king and keep himself out of the clutches of the Inquisition. “Nobody expects the Spanish Inquisition!”, says Monty Python, but Goya did. He experienced their intimidation in 1799 and didn’t want to feel it again.

Goya was also a printmaker; he made etchings and engravings — usually combining the two processes — plus a few lithographs. In fact, aside from Rembrandt, Goya was the greatest printmaker who ever lived. His set of 80 Caprichos (1799) are satiric, nightmarish, tragic and absurd. They depict witches and demons, corrupt nobles and clergy, victims of persecution, and assorted chimeras. The most famous of these prints is no. 43, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters.” It shows the artist asleep at his work-table while all sorts of creatures – bats, owls, a cat and a lynx – hover, prowl, or stand watch nearby. It’s message is that artists must exercise logic and reason or else the demons of superstition will take charge. It’s also sometimes taken to mean that enlightenment and barbarism exist in close proximity, and that the latter is always poised to overwhelm the former. Like all the Caprichos, the title is inscribed at the bottom; here and elsewhere, the words inflect, deflect, derange and amplify the images.

Francisco Goya, “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters,” Los Caprichos, 1799.

The Disasters of War was another album of 80 prints and associated captions. They represent Goya’s private response to the period of civil war just mentioned and were never sold in his lifetime. Many are brutal images of dismembered bodies, piles of corpses and scenes of famine, anticipating photographs made at Auschwitz and Dachau after their liberation from the Nazis in 1945. Others show hand to hand combat, torture, and execution by garotte. The one I bought, no. 79, “Truth Has Died,” is allegorical. It shows Truth as a dead, female figure in an open grave with a cowled monk, a mitered Cardinal and other figures gathered around her. In time of civil war, Goya suggests, Truth is the first casualty. Or does he mean that after Truth dies, intolerance and violence rage?

These prints are visually complicated, and Goya used all sorts of tools to make them so: etching needle, aquatint, engravers burin, roulette, burnisher and scraper, resulting in a very animated surface. He liked to experiment, and every single work is a display of the printmaker’s skill as well as being intellectually and emotionally compelling. Meaning evaporates beneath the abstract skein of marks; expression emerges out of the random-seeming gouges and scratches. But however virtuosic these prints are, they are not rare. Goya published hundreds of each, and because impressions were pulled long after his death, they continued to accumulate. I’d estimate there are more than 100,000 prints by Goya in existence. Of those, perhaps half are in public collections, many bound up in albums. So, with about 50,000 in circulation, it isn’t hard to find them for sale at auction, in galleries, or even on eBay.

Beeple

Until two weeks ago, I’d never heard of Mike Winkelmann, or Beeple. But that’s not surprising. There are approximately 1.4 million working artists in the U.S., 200,000 of whom make their living by their art alone. Even though I sometimes write contemporary art criticism, I doubt I’ve heard of more than .05% of them. But even if I were a critic who regularly visits all the major art galleries in New York, Los Angles and Chicago, and reads all the print and online art magazines, it’s unlikely I would have heard of Beeple. He’s a digital artist based in Charleston, South Carolina, well outside the artworld center of gravity, and works in a medium that until recently was not much supported by art schools, commercial galleries and museums: digital art, sold in the form of NFTs, secured by blockchain technology. Until two weeks ago, I couldn’t have written the second half of that sentence.

Here’s how the business works: 1) a company, for example Nifty Gateway, creates an NTF website; 2) artists such as Beeple post their works on the site – either jpegs or original digital art; 3) Spectators visit the site, see the works and may even download them. But if anybody want to actually own an artwork, they have to buy the unique NFT assigned to it. And just to make sure that ownership is uncontested, the transaction is documented in a cryptographic ledger called a blockchain which, because it’s linked to all previous and subsequent records of transfer or sale, can’t be altered without messing up the whole chain and everybody knowing about it. There’s lots more to be said about blockchains: for example, that they were invented about 13 years ago as a peer-to-peer way of securing barter and sale without the control of central institutions such as banks or government regulators; that corporate use of blockchain technology has grown exponentially in recent years; and that the quantity of cryptocurrency protected by blockchains is growing fast. The best known of these currencies is Bitcoin, with a current market capitalization (the total value of all Bitcoins) of about $1 trillion. Lots of people buy cryptocurrencies – like my daughter, Sarah. When she was a teenager, she knew no more about money than the insides of my trouser pockets. Now in her 20s, she bought $600 worth of Omi cryptocurrency last year that’s worth $25,000 today. What it will be worth tomorrow is another question.

Beeple began making digital art in 2007 after a few years designing websites, producing animations for live events, and selling designs to high-end fashion houses. He decided at that time – apparently as a kind of discipline – to make one art-work every day. (Lots of artists do that, by the way.) His earliest efforts were drawings posted online: mostly portraits, clowns, and cartoon characters, as well as abstract patterns. They aren’t very good, but at their best, they recall Mike Kelley, a celebrated artist active in Southern California from about 1978 until his death in 2012. Kelley’s early drawings of chimeras, hermaphrodites and anthropomorphized animals were similarly adolescent in sensibility. Beeple however, lacked Kelley’s punk attitude and expressiveness, and many of his first Everydays were even racist or sexist: Black and Asian men, naked women and politicians including Barak Obama with a wide, toothy grin, and various versions of Hilary Clinton: with bad teeth, an erect penis, or a forked tongue.

His subsequent works, culminating in his recent, 3-D graphics are less offensive but still vulgar. They often suggest narratives with a science fiction-feel, as if influenced by the TV program, Black Mirror (Channel 4/Netflix, 2011-2019). More often, they recall “gross-out” comics, movies and trading cards, like the Garbage Pail Kids. Toward the end of the Trump administration, Beeple’s work became more political, though it’s difficult to discern the valence of an image like the one dated January 6, 2021, titled Endgame: A naked Trump sits astride the Capital dome, flashing a thumbs up while rioters fight police below.

None of Beeploe’s recent works are drawn or painted. They are the product of software that allows him to choose from among thousands of images, manipulate and then photograph them. He recently told Kara Swisher of the Times:

And so, you can just buy these models, and then you can use them and stuff, [and] with one click, pull those into the scene. And then I can sort of pose them, put them wherever I want, scale them up, scale them down. It’s almost like playing with toys. I’ve got the biggest, best toy collection. I could break them apart and put a new head on, a new body on, new arms on, whatever. And then sort of set up these scenes and take a picture of it.

In 2020, Beeple was approached by Nifty Designs to put his works on their website and enter the emerging NFT market. His first sales were highly successful, but nothing like the Christie’s auction two weeks ago that made all that money. Everydays: The First 5,000 Days is not actually a single artwork; it’s a catalogue of all Beeple’s images turned into a mosaic — on my laptop it looks like a detail from a portrait by Chuck Close. But it can also be viewed as individual images. What’s most remarkable about the whole enterprise, however, isn’t the puerile character of the work and the amount of money it made; it’s the location of the art within the current network of financialized capital.

NFTs and Capitalist Financialization

The two buyers of Everydays are Vignesh Sundaresan (aka Metakovan) and Anand Venkateswaran (aka Twobadour). Their motivation for spending so much money, they wrote after reporters revealed their identities, was to diversify the mostly white, high-end art market by introducing “a dash of mahogany to that color scheme.” The men are from Tamil Nadu (they currently live in Singapore), but their purpose was probably not so much ethno-nationalist as profit seeking. They plan to use Everydays as the anchor for an art investment portfolio they just launched. Dubbed Metapurse, the fund will allow buyers to acquire part-shares in digital art works, and then trade them like any other NFT using a newly minted cryptocurrency called B-20. In this way, the art collector will be buying art – or fractions of artworks — and trading in a new cryptocurrency at the same time. Plenty of companies including OpenSea, Rarible, Grimes and Nifty Gateway, already sell digital art in the form of NFTs, but they usually use Bitcoin or Etherium (or even hard cash) as tender. In the case of Metapurse, the art and the coin are essentially the same. As Beeple told Swisher: “It’s even further away from the actual artwork and very much into a financial instrument….So I’m kind of like, O.K., well, you can sell that, and if you can sell it to your crypto people, you go for that.”

NFT artworks are convenient for investors for a number of reasons. For very rich people lacking knowledge or experience with art or art buying, the system is undemanding. Instead of inventing an explanation for their love of say, Egon Schiele, Jean-Michel Basquiat or Christopher Wools (when their only ambition is to stash the art in a storage unit), NFT collectors can quickly buy and sell art shares without ever having to form or justify their taste. Rather than trying to cozy up to the intimidating, art gallery gatekeepers at Zwirner, Gagosian or Hauser and Wirth in order to obtain the choicest works by the hottest artists, crypto-collectors can buy and sell art from their laptops without talking to a soul. (For that reason, NFTs may also be useful vehicles for money laundering – they fly beneath the radar of corporate compliance officers.) In addition, no expensive overhead is involved in collecting NFTs: no art movers, installers, insurance costs, storage fees, or auction commissions. The Christie’s sale was a marketing stunt – auction houses interfere with smooth NFT transfers and are unlikely to be involved in many future sales.

Unlike other collectables, the price of which is affected by the venue in which it is sold (flea market, eBay, gallery, or auction house), NFTs are sold only on single, designated platforms, so pricing is easy. Additionally, there is no need for the collector of NFTs to learn the arcana of art connoisseurship. With Goya prints – a few rare examples of which can fetch more than $100,000 — the serious collector needs to recognize subtle shades of ink, types of paper and their watermarks, learn about plate beveling, distinguish the difference between aquatint and plate tone, and be able to discern burnishing marks and burr.

Obviously, none of that matters for the appreciation of Everydays which has no physical presence at all. Nor do Beeple’s investors have to be bothered by pesky issues about politics and power, such as those raised by Goya in his Caprichos and Disasters. What politics exists in Beeple’s NFTs is sufficiently cloaked or cliched that it can simply be overlooked, or else enjoyed as pure spectacle. And that’s true for most of the NFTs I have found. Indeed, the platform interface of NFT art sites like Nifty Gateway, Rarible and Superrare resemble those for XVideos and PornHub; they don’t exactly encourage extended, critical scrutiny.

Under the emerging digital art system represented by the Beeple sale, art can finally become what many investors have long wanted it to be: a financial instrument divorced from capitalist production, and a hedge against fluctuations in currency, equities and commodities markets. As is well known, an increasing amount of corporate profit in the U.S. and globally is derived from financial transactions – stocks, bonds, derivatives, and hedge funds — and less from the production and sale of physical goods. The rise of the stock market in 2020-21 in the midst of near economic collapse is recent evidence of the financialization of the economy. This “fictitious capital,” as Marx called it (Capital, vol. 3, chapter 25) is however, inherently risky. Since corporate profits no longer rest on a solid foundation of production and consumption, the danger of a bubble is great. And the risks to cryptocurrencies such as Bitcoin and Etherium are greater than other financial instruments because there is as yet no chance that the U.S. Federal Reserve or Congress will step in to protect these assets in case the bubble bursts. The hope of crypto-art investors is that NFTs will function as an asset hedge, just like physical works of art, precious metals, T-Bills and cash during recessions and depressions. If nothing else, they might function as social or cultural capital, protecting the good name of investors and putting them in advantageous positions when the economy is righted.

Collecting Goya offers few of these potential advantages, and the price of his prints, like that of most “old master” prints, is likely to continue to decline as the value of NFTs and other financial hedges rises. Because printmakers until relatively recently published unlimited editions (the very concept of an edition dates to the late 19th Century), art investors find it hard to confidently predict their appreciation. Prints are fungible by definition, and as their price falls, the price for non-fungibles rises to astonishing heights.

NFTs exist within the neo-liberal order of financialization, a system that has created the most unequal U.S. and global economy in world history. Subject to the stresses of stagnation, inflation, inequality, racism, and climate change, that system must inevitably collapse. But until that time, I’ll keep buying inexpensive etchings by Goya.

Optimistic postscript: Perhaps the most peculiar thing about NFT trading schemes like Metapurse is that in turning art into a form of money, it is inadvertently scripting the communist dream of eliminating money altogether and having art (or skilled services) function as a universal currency. After the revolution, one person could trade his etching for another person’s piano performance, for another person’s carpentry and so on, all recorded for posterity on a blockchain. In this system – anticipated by William Morris in his utopian romance, News From Nowhere (1889) – there will be no financial hierarchy or indeed even social classes. Wealth would not be accumulated, except in the form of experience and wisdom, and making war over the right to own and plunder the earth would make no sense. A future online marketplace for NFTs, would thus resemble the physical market in central London, as imagined by Morris:

As he spoke, we came suddenly out of the woodland into a short street of handsomely built houses, which my companion named to me at once as Piccadilly: the lower part of these I should have called shops, if it had not been that, as far as I could see, the people were ignorant of the arts of buying and selling. Wares were displayed in their finely designed fronts, as if to tempt people in, and people stood and looked at them, or went in and came out with parcels under their arms, just like the real thing.

If we could all freely access digital art without feeling the need to own any of it – and support the artists through a system of barter or labor exchange – I’d be all for it. Go Beeple!