Most sports teams have a dedicated fan base. Most often, that fan base is mostly composed of people who live or lived in the region the team is located. Many of these fans grew up with their favorite team, watching players come and go, championships missed and won; they have opinions on the players, the games and the moves made by the team management. These opinions flare in bars, school rooms, on talk radio and on the internet. The intensity of the arguments can reach a temperature comparable to arguments between two strongly opposed political foes or even that between disappointed and angry lovers. It is very rare that fans become fans of a certain team because of their politics, although it does happen. The world’s best example of just such a team is the German football (soccer for you US people) club based in the Sankt Pauli district of the northern port city of Hamburg.

Like most port cities, Hamburg is known for its night life and the availability of pretty much anything human desires might crave. Bars seedy and not, sex workers of all kinds, hashish, heroin, methamphetamine and other modifiers of the human reality—the reputation of Hamburg is deserved, even though the city fathers and mothers might wish it were otherwise. The Reeperbahn is one of Hamburg’s districts where the aforementioned vices have on occasion abounded in between police sweeps and attempts to gentrify the area. It is also the home of the St. Pauli football club and the site of one of the longest running squats in Europe. The residents of that and other squats comprise a number of the football team’s world-(in)famous fan base. Anarchist, leftist and antifascist, the renegade element of the St. Pauli fan base has expanded from the streets and squats of Hamburg’s Reeperbahn to almost every city in Germany and into the world beyond.

This expansion of the fan base had little to do with the club’s win-loss record. Indeed, the club has mostly bounced between the second and third tiers of the German Bundesliga since the 1960s, sometimes slipping even lower. Nor was the increase of the team’s popularity originally due to any effort by the club’s management. Instead, it was the adoption of the team by football-loving leftists, anarchists and the lumpen of the Reeperbahn. These fans, waving the skull and crossbones flags that represent the team, made the St. Pauli FC their own and the stadium’s standing room sections a place to gather, cheer on their team and make political statements. Sometimes those statements were related to efforts by more conservative fans to control the fan base and sometimes the protests were against efforts by the club ownership to commercialize the stadium and the team. More often, though it seems the protests and political displays were responses to fascist football fans, sexist behavior and advertising demeaning women, and against racism in football. When squats were attacked by police working for the bankers and developers hoping to gentrify Hamburg, the stands would often end up as one more venue in the battle against the police and their employers.

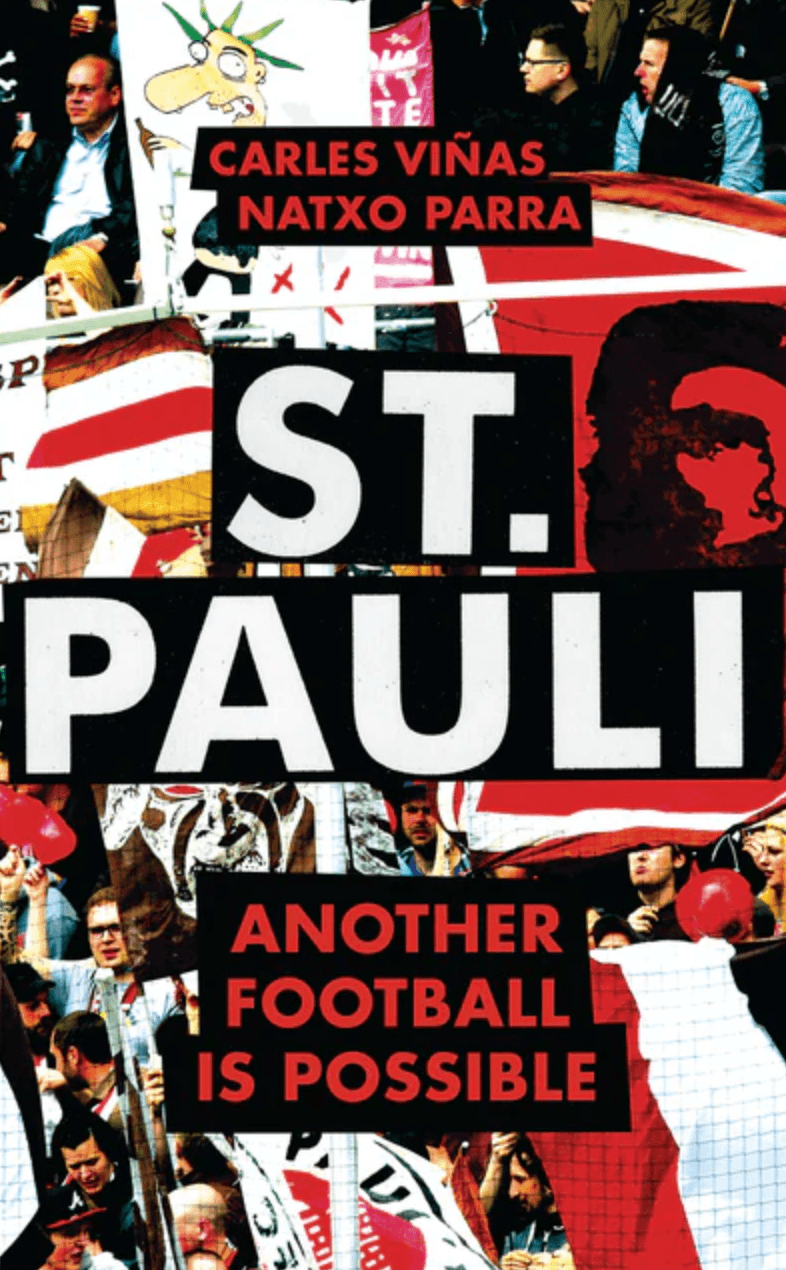

Pluto Press recently published a history of the team. Titled St. Pauli: Another Football is Possible, and written by historian Carles Viñas and labor lawyer Natxo Parra, the book is a partisan look at the symbiosis that describes the club and its radical fans. Between anecdotes about the neighborhood and the team, the authors provide an engaging history of the intentionally political fans and their interaction with the players, fans of other clubs and the politics of Hamburg, Germany and the world. It is a tale unlike any other sports team, even those with extremely passionate fan bases like the Boston Red Sox baseball team in the United States or Liverpool, England’s Reds. There are no sections of radical cheerleaders at Fenway Park or Liverpool’s Anfield, after all. Nor are antifa banners being hoisted near the Pesky Pole or even at the Kop. The only riots in Boston’s Fens, where Fenway Park is located, came after the team finally beat their arch-rivals the New York Yankees for the American League Championship in 2004.

This then is a story of a rarity in the sports world—a team whose fans not only support, criticize and hope their chosen team excels, but who also believe they have a say in the way the team treats its players, its audience and the geographic area it represents. Furthermore, it is a story of a fan base who understand sport is not apolitical, but is quite possibly one of the better venues in modern capitalist culture where politics should be applied. The warmakers and other profiteers certainly understand this. Why else would their warplanes fly over the Super Bowl and every inch of every sports building, field or pitch be covered with advertisement?