The coronavirus pandemic is lethal, but could there be a silver lining beyond the pain? Social media is awash with how the newly cleaned environment is hosting wildlife not seen for years. Dolphins are swimming in Venetian canals: except they aren’t, they’re really near Sardinia as usual. Swans? Yes, but they’ve always been there. The canals may be cleaner but the story’s fake.

The coronavirus pandemic is lethal, but could there be a silver lining beyond the pain? Social media is awash with how the newly cleaned environment is hosting wildlife not seen for years. Dolphins are swimming in Venetian canals: except they aren’t, they’re really near Sardinia as usual. Swans? Yes, but they’ve always been there. The canals may be cleaner but the story’s fake.

Facts matter less than our ache for an unpolluted globe. We yearn for a lost world of childhood innocence, and so project our hope onto juvenile activists. But there clearly are benefits in the reduced use of fossil fuels as flights are cancelled and car journeys shrink to levels last seen on distant Sundays when the shops were shut. Some are reporting easier breathing during an epidemic which attacks the lungs.

Surely this will strengthen the current insistence to turn thirty, even fifty, percent of the globe into “protected areas” (PAs)? We’re told this is the answer to climate chaos and protecting biodiversity – no people, no pollution, problem solved?

I’m afraid not: doubling PAs won’t lessen climate change, it’ll make things worse. Like dolphins in the Grand Canal, this so-called “New Deal for Nature” is fiction. PAs in places like Africa and Asia are often disastrous. They evict people from their traditional lands and deprive them of their self-sufficiency, forcing them into city slums and a hostile money economy. People are beaten and killed if they try to return to their land, even to collect firewood. Their resentment grows. Where they’re tough enough, they cut fences and fight back. It’s happening now in Kenya where conservation is seen as a colonial land grab, enriching outsiders and NGOs but ratcheting up local hostility.

Gangs of armed rangers won’t be enough to protect this colonial “fortress conservation”. Those promoting it preach sustainability, but themselves pursue an unsustainable model because there won’t be any PAs left in Africa in a generation, they’ll be overrun by angry and hungry Africans.

Evicting people is both criminal and tragic because the same local people, usually indigenous to the area, are the best stewards of their environments. If they weren’t, they’d never have thrived in lands which we see as wild. Our concept of “wilderness” has roots in European folklore but also in white supremacist ignorance: the apparent wildernesses were in fact shaped by humans over thousands of years.

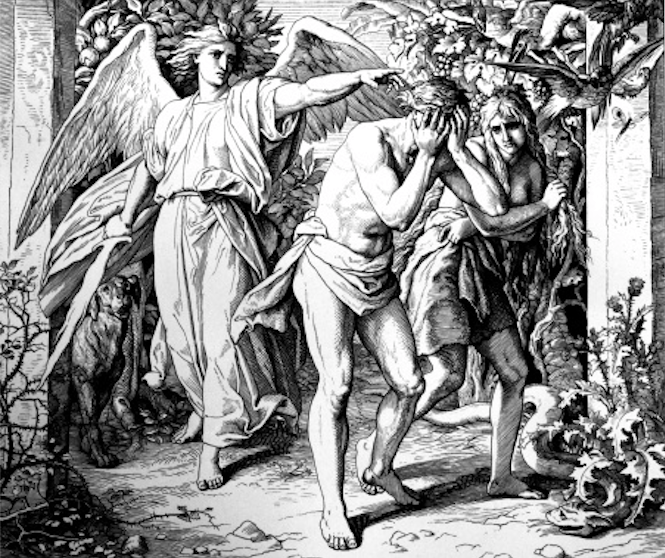

The myth echoes the Biblical Eden, dyed with Stygian hue. Often called “ecofascism,” it asserts that some people, “foreigners”, are expendable if it makes the world cleaner and purer. An extreme expression can be read in the manifestos of racist terrorists like the Christchurch shooter, but the same undercurrent drives social media mobs baying for “poachers” to be summarily killed – never mind that some of them are locals trying to feed their families. There’s an ecofascist tone in a joke from former WWF president, Prince Philip, who wanted to reincarnate as a virus to curb overpopulation! We’re now told the real virus is humanity itself, although billions of people consume very little. And we’ve all seen the wildlife films where Africa is mysteriously devoid of Africans.

That omission is contrived, but some of the emptiness is real: millions of indigenous people have already been “disappeared” to make room for PAs. Doubling these areas would entail the theft of the lands and resources of hundreds of millions more. It’s a mad, bad idea which would finish conservation. It’s time to clean ecofascism out of environmentalism.

The conservation industry should instead be offering its huge resources to local people who actually ask for projects on their land under their own control. Eighty percent of Earth’s biodiversity is already in indigenous territories and it’s proven that local people can achieve better conservation at a fraction of the cost of alternatives. We must reject ecofascism and bring human diversity into the centre of conservation. We have to do it now because those who live most differently to us have some of the best answers about how to live at all.