The weeks following an underwhelming Brazil-Russia-India-China-South Africa (BRICS) mid-September summit in Goa and the United States presidential election in November have unveiled ever-widening contradictions. Thanks to blatant corruption, presidential delegitimation has reached unprecedented levels in both Brazil and South Africa; while ruling-party religious degeneracy in India also included an extraordinary bout of local currency mismanagement; and sudden new foreign-policy divergences may wreak havoc in China and Russia. The BRICS bloc’s relations could well destabilise to the breaking point.

Even before the next major world recession arrives, probably within two years, the inexorable rise of intra-bloc conflict will be apparent at the September 2017 BRICS summit in Xiamen, China. Most obviously, the Brasilia, Moscow and New Delhi regimes are shifting towards Washington while those in Pretoria and Beijing are spouting well-worn anti-imperialist rhetoric, just as Donald Trump and his unhappy mix of populists, paleo-conservatives, neo-conservatives and neo-liberals take power on January 20.

We should have been more concerned about these power relations much earlier. For more than a decade, Washington militarists and their academies allies (like Keir Lieber and Daryl Press) have believed that “the United States now stands on the cusp of nuclear primacy… [having] the ability to disarm the nuclear arsenals of Russia or China with a nuclear first strike.” Such men are further empowered by Trump’s Christmas-time threat to any opponent that he would engage in “an arms race. We will outmatch them at every pass and outlast them all.”

In spite of regular promises to disarm the nukes, outgoing president Barack Obama’s recent recommitment to a new generation of precision-guided mini-warheads will not only cost more than $1 trillion over the next three decades, but also makes their use “more thinkable,” according to one of his top strategists.

And in several other ways Obama’s legacy set the stage for the worst of Trump’s coming policies: economically empowering the top 1% at the expense of the vast majority, continuation of a belligerent foreign policy, promotion of corporate interests across the world, denial of civil liberties especially to refugees and prisoners, and construction of a vast surveillance capacity by Washington’s deep state.

Still, while each of these dangerous elephants trample the grass underfoot, there are a few surviving blades – the subject of a coming essay. Only grassroots initiatives offer encouragement for a bottom-up anti-imperial afterlife following the top-down imperial, inter-imperial and sub-imperial follies of 2017. The main point of the pages ahead, though, is that whether in Washington or BRICS capitals, the wedge may well work but the broader right-wing agenda will fail.

Tensions in Taiwan

To illustrate the insanity ahead, one ‘country’ seems poised to centrally play at least a symbolic role: Taiwan. In late December, Solly Msimanga – the centre-right mayor of South Africa’s capital city, Pretoria, elected just four months earlier – visited Taipei to seek out trade and investment opportunities, following an invitation from his counterpart in Taiwan’s capital.

The prior municipal political establishment became as wild-eyed-angry about this trip as were Chinese elites about the December 2 congratulatory phone call Trump happily took from Taiwan’s president Tsai Ing-Wen. Reflecting an unusual global sensibility, the African National Congress (ANC) branch that had ruled the city for the prior two decades furiously complained that Msimanga’s trip “exposed the conspiracy against BRICS countries… We are without doubt characterising this trip as treason” (sic).

The national Department of International Relations and Cooperation spokesperson, Clayson Monyela, reiterated that Msimanga “was advised against undertaking this trip. The SA government respects the One China policy.” Actually, Monyela’s unit has its own Taipei Liaison Office which promotes cooperation in biomedicine and auto electronics. Likewise the Taiwanese have Liaison Offices in Pretoria and Cape Town.

Indeed dating to 1996 when Taiwan held its first-ever democratic presidential election, Nelson Mandela had committed to recognise a government which “supported us during the later phase of the struggle… It is not easy for me to be assisted by a country, and once I come to power, say ‘I have no relations with you’. I haven’t got that type of immorality, and I will not do it.” The ‘support’ was merely a bribe: in 1993-94, Taipei officials donated $20 million to the ANC for its election campaign, a U-turn after a long history of the pro-US military regime’s collaboration with apartheid. (Mandela similarly celebrated Indonesian dictator Suharto in 1997, after receiving his taxpayers’ similarly generous donations.)

Always exhibiting his deal-making instincts, Trump had replied to critics, “I don’t know why we have to be bound by a One China policy, unless we make a deal with China having to do with other things, including trade.” (Washington had recognised One China since 1979, as had the UN General Assembly since 1971.)

One reasonable response from Taiwan was a request not to be used as a bargaining chip. Complained a “very annoyed” researcher, June Lin from the Taipei-based Formosan Association for Public Affairs, “Trump tried to be free and easy, but he is very specific about the exchange deal: ‘Who cares? Unless you give me A and B and C, or I won’t give a damn.’”

A Chinese state mouthpiece, the Global Times, threatened that if Trump “openly abandons the One China policy, there will be a real storm. At that point, what need does mainland China have for prioritising peaceful unification with Taiwan over retaking the island by military force?”

War is one scenario but an economic blockade is more likely, given Taiwan’s reliance on China, especially sending world-leading semi-conductors to the desperately dependent West via eastern mainland China’s high-tech assembly facilities. One Beijing official told Reuters, “We can just cut them off economically. No more direct flights, no more trade. Nothing. Taiwan would not last long. There would be no need for war.”

Moreover, if Trump continued to be – as the Global Times put it – “as ignorant of diplomacy as a child,” then China would aid (unspecified) anti-US forces. “This inexperienced president-elect probably has no knowledge of what he’s talking about. He has overestimated the US capability of dominating the world and fails to understand the limitation of US powers in the current era.”

If Trump is merely an ignorant conman, as seems the case, he nevertheless has a potent instinct for divide-and-rule rhetorical flair, confirmed by his support in the US white working class. Trump’s economic localisation slogan “Buy American and Hire American” may, in turn, combine with his geopolitical deal-making to become a major wedge between the BRICS. For behind the resurgent inter-imperial sentiments lie vast economic contradictions that now appear beyond the capacity of multilateral capitalist regulation to resolve.

Rightwing or leftwing localisation?

Beijing will certainly face worsening problems with Trump, given the latter’s propensity to blame trade competition – specifically, subsidised Chinese exports and currency devaluation, as well as alleged Chinese commercial computer hacking – for US deindustrialisation. Advised by the notorious Sinophobe economist Peter Navarro, Trump’s answer is a series of localisation-oriented policies that will allegedly benefit US manufacturing industry by increasing protection from foreign imports with what may be a 45% tariff on China and 10% on goods from other overseas sources.

Centre-left economist Joseph Stiglitz warns against Trumponomics, in part because of the lack of redistribution that might make such high import tariffs feasible: “Higher interest rates will undercut construction jobs and increase the value of the dollar, leading to larger trade deficits and fewer manufacturing jobs – just the opposite of what Trump promised. Meanwhile, his tax policies will be of limited benefit to middle-class and working families – and will be more than offset by cutbacks in health care, education, and social programs.”

A trade war is just as likely an outcome, reminiscent of the protectionist Smoot-Hawley Act of 1930 which is credited with contributing to the Great Depression. Like that period, the major question is in which direction populist sentiments channel working-class politics, rightwards or leftwards. (A coming essay considers the left option.)

Momentum in most sites is enjoyed by right-wing leaders: the US (Trump), Britain (UK Independence Party and Brexit supporters), France (National Front led by Marine le Pen), Germany (Alternative for Germany) and the Netherlands (Party of Freedom led by Geert Wilders), with the latter three holding elections in 2017, along with Italy whose Five Star Movement (led by comedian Beppe Grillo) also has right-populist support.

If this tendency continues to prevail, we can expect the widespread emergence of what is often termed a ‘fascist’ regime: when the populist sentiments of working-class people are revealed as nativist, racist, misogynist, homophobic, xenophobic, Islamophobic, anti-Semitic, ablist and anti-ecological, when imperialist and militaristic sentiments are acted upon, and when the socio-cultural agenda of the right is conjoined with corporate power to take control of the state.

In the period 2017-20, the dominant alignment appears to be a combination of far-right socio-cultural politics with mega-corporate interests, at least in the US. (In Britain, the City of London’s financial-corporate agenda conflicts more explicitly with the far-right’s Brexit strategy.) It became clear immediately after the election that Wall Street’s giddy investors expect military, financial and fossil fuel industry stocks to prosper far more than any others, as the Dow Jones index hit a new record.

Trump promises to lower corporate taxes from 35 to 15% and rapidly inject what might be called ‘dirty Keynesian’ spending on airports and private transport infrastructure, heralding a new boom in US state debt. Along with the Federal Reserve’s rise in interest rates, this in turn will at least initially draw more of the world’s liquid capital back into the US economy, similar to the 2008-09 and post-2013 shifts of funds that debilitated all the BRICS currencies aside from the Chinese yuan.

New alliances loom as several BRICS continue to crumble

With Trump’s election and the resulting rearrangement of geopolitical alliances and economic uncertainty, the BRICS will be under increasing pressure on several fronts. One winner may well be the Russian economy, as a result of loosening sanctions and the higher oil prices that will likely result from the December 2016 Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries agreement. At rock bottom in February 2016, the price per barrel had fallen to $27, but by year’s end it was $55, giving some prospect of relief to the Russian economy.

Nevertheless, as the world becomes more geopolitically dynamic and economically dangerous – what with ongoing Chinese overcapacity, unprecedented global corporate debt while profit rates continue falling, worsening stagnation and rising financial meltdown risks emanating from weak European banks such as Germany’s Deutsche as well as several Italian banks – the political coherence of the BRICS bloc is in question.

Trump’s election heralded a period ahead in which the BRICS’ dubious claim to building a counter-hegemonic world politics will falter even faster. Two leaders – Brazil’s Michel Temer and India’s Narendra Modi – have strong ideological affinities as conservative nationalists.

Temer’s government, installed in May, has come under intense pressure because of ongoing popular delegitimation of his constitutional-coup regime, in part from unions which had supported the predecessor Workers Party. Temer’s closest allies (e.g., Renan Calheiros and Eduardo Cunha, who arranged former president Dilma Rousseff’s downfall in the Congress, and six of his cabinet ministers) were repeatedly exposed as far more corrupt than the prior president, thanks in part to plea bargain confessions by 77 officials of the Odebrecht construction companies involved in political bribery.

In December, Temer’s government imposed a new 20-year austerity regime that is certain to generate a coming period of unrest. Temer’s two 2016 trips to Asia – to appear with the G20 and especially with other BRICS leaders at the Goa summit – represent one means of distraction from such troubles.

In India, six weeks before hosting the 2016 summit, Modi suffered a strike of an estimated 180 million workers demanding both higher wages and an end to his neoliberal (austerity-oriented, pro-corporate) economic policies. Although his Hindu nationalism assures a strong base, Modi soon became even more unpopular with the non-sectarian working class and poor (amongst others) due to his chaotic banning of large currency notes (500 and 1000 rupees) that make up 86% of the money in circulation. This left many rural areas virtually without cash and hence without economic activity, and banks were compelled to restrict funds withdrawals to small daily amounts.

Modi also attempted, albeit unsuccessfully, to use the Goa summit for intense (albeit unsuccessful) ‘anti-terrorist’ lobbying. The economic and political links that China and Russia have built with the Pakistani government – as it has progressively delinked from Washington in the wake of the 2011 Osama bin Laden execution – remain more attractive than remaining in India’s favour within the South Asian rivalry.

A third leader, South Africa’s Jacob Zuma, seems to require BRICS anti-imperialist myth-making to shore up his internal legitimation, as part of the ANC’s so-called “talk left, walk right“ tendency. For example, in November 2016 Zuma explained BRICS to party activists in the provincial city of Pietermaritzburg: “It is a small group but very powerful. [The West] did not like BRICS. China is going to be number one economy leader… [Western countries] want to dismantle this BRICS. We have had seven votes of no confidence in South Africa. In Brazil, the president was removed.”

The following week in Parliament, Zuma was asked by an opposition Member of Parliament which countries he meant, and he replied, “I’ve forgotten the names of these countries. How can he think I’m going to remember here? Heh heh heh heh!,” he chuckled.

It is evident that Zuma will continue to use the BRICS as a foil for such defensive sentiments, even though his government’s initial endorsement of the NATO bombing of Libya in 2011 was the most egregious case of the BRICS’ geopolitical role in Africa, against the African Union’s wishes (and to be fair, Pretoria did reverse course and opposed further intervention). Behind the scenes, US journalist Nick Turse has identified the Pentagon’s “war fighting combatant command” in dozens of African states, mainly directing local proxies.

It soon transpired that there was a blunt division of labour at work between Washington and its deputy sheriff in Pretoria. At the conclusion of his 2014 meeting with Obama as part of a US-Africa heads-of-state summit, Zuma identified a chilling conclusion: “There had been a good relationship already between Africa and the US but this summit has reshaped it and has taken it to another level… We secured a buy-in from the US for Africa’s peace and security initiatives… As President Obama said, the boots must be African.”

The theatrical aspects of BRICS will continue, apparently designed in part for the local consumption of constituencies who want to see their leaders standing tall internationally in part because of rising local problems. But the most dynamic and contradictory terrain of BRICS to consider is their role in global geopolitics.

BRICS play the global game

Armed conflicts and extreme tensions certainly affect the BRICS directly and in their immediate regions: Syria, Ukraine, Poland, Pakistan, the Korean Peninsula and the South China Sea. In addition, global power balances are adjusting because of dramatic 2016 shifts of leadership loyalties from West to East in Turkey and the Philippines encouraged by Russia and China, respectively.

Meanwhile, the last two years have witnessed major armed (including civil) conflicts continuing in Syria, Afghanistan, Turkey, Pakistan, Mexico and northern and central Africa. Aside from extremist groups such as the Islamic State, Boko Haram and Al-Shabaab, the main belligerent bloc of states catalysing violence in the world today is centred on Washington.

The most dangerous such state network continues to feature Israel, Saudi Arabia and Qatar in the Middle East (the latter two of which split favours in funding both Islamic extremists and the Clinton Foundation). Misery, displacement, refugees and brutal repression are evident, as a result, from Palestine to Syria to Yemen, while the Pentagon and State Department are themselves directly responsible for infinitely destructive chaos in Libya, Afghanistan and Iraq. Vladimir Putin’s decision to defend Syria’s corrupt, dictatorial Bashar al-Assad regime in turn led to extensive war crimes against civilians such as bombing East Aleppo.

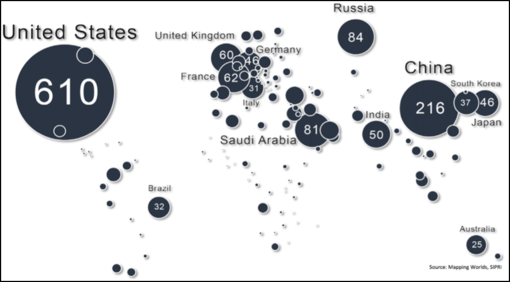

Beyond the Middle East, it is always tempting for Western powers to provoke incursions in the BRICS’ regional sites of accumulation and geopolitical influence. The North Atlantic Treaty Organisation’s conflicts with Russia in Georgia, the Ukraine, Poland, Syria and Turkey, and the US Navy with China in the South China Sea, have been most important in recent years. The US dominates world military spending, with $610 billion in direct outlays in 2014 (and myriad other related expenses maintaining Washington’s control such as US AID). But four of the five BRICS also spent vast amounts on arms: $385 billion in 2015 (of which 55% was China).

World military spending, 2015

Source: Bank of America

There are various other sites of contestation, e.g. over Washington’s (and its ‘five eyes’ allies’) capacity to tap communications and computers through the internet. After revealing the US National Security Agency’s (NSA) snooping capacity in 2013, whistle-blower Edward Snowden has an apparently safe Moscow exile, after fears of extradition to the US or worse. A few months later, Rousseff cancelled the first visit by a Brazilian head of state to Washington in 40 years, as a way to protest Snowden’s revelation that the NSA was tapping her phone.

In this context of split loyalties, two quite unpredictable processes are in play at the time of writing, centering on Russian and Chinese relations with Washington. First, in Russia, Putin was accused by Obama and by the defeated candidate Hillary Clinton of assisting Trump to win the November 2016 election through email hacking, a matter that may be clarified in January if US intelligence agencies manage to prove the case. But these agencies failed repeatedly on prior occasions, and on December 29 even Obama failed to offer conclusive evidence of wrongdoing when he expelled three dozen Russian diplomats accused of spying.

At the time of writing, WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange still denied he had access to leaked emails from any direct Russian source. A former British ambassador, Craig Murray, claims mid-2016 Democratic National Committee leaks were given to him by an internal Democratic Party whistle-blower, to pass to Assange. Another election email scandal involved the hacking of Clinton’s campaign chairperson, John Podesta, whose security advisor admitted that he accidentally made Podesta vulnerable in a phishing scam designed to acquire his password.

Putin responded to Obama’s late-2016 attacks merely with scorn, saying he would await the presidential transition, and was immediately congratulated by Trump. Putin not only recently bragged, “Of course the US has more missiles, submarines and aircraft carriers, but what we say is that we are stronger than any aggressor, and this is the case.”

Yet Putin’s critics remind that the Russian government is being successfully prosecuted for widespread doping of Olympic athletes, a charge once denied but now confessed. Given Putin’s hatred of the US State Department – for valid reasons, such as its role in the Ukrainian regime change in 2014 and destruction of Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya and Yemen in recent years – there is no question that he both favoured the election of Trump and had the spy-craft capacity to make an intervention.

Putin also enjoys alliances with several far-rightwing allies in Europe and he anticipates a dramatic adjustment in the Western balance of forces thanks in part to Trump’s prolific personal business interlocks with Russia. Benefits to Putin will begin with the relaxation of sanctions associated with Russia’s 2014 invasion of the Ukrainian (former Soviet) province of Crimea, recognition of Moscow’s sphere of influence in the ex-Soviet Union, and potentially also a rising oil price.

One dilemma for the Trump administration is that his own party and the Democratic Party have been conditioned to despise Putin for more than a decade. But Trump surprised the establishment with the appointment to the position of Secretary of State of the pro-Russian ExxonMobil chief executive Rex Tillerson. There could be a resurrected $500 dollar Siberian oil deal for ExxonMobil – whose implementation was interrupted in 2015 – if Washington soon ends US sanctions against Russia, as is widely anticipated.

As Guardian columnist Julian Borger reports, powerful critics believe Trump’s “opaque ties with Russia and his glaring conflicts of interest represent existential threats to US democracy. Trump is giving the nod to Tillerson, the recipient of Moscow’s Order of Friendship, as a slaughter is underway in Aleppo, likely to be one of the worst war crimes of the century so far, in which Russia is complicit.”

Moscow’s Sputnik news expects mediation by Henry Kissinger to mutual advantage. But this is dangerous, warns former Reagan Administration official Paul Craig Roberts: “Kissinger, who was my colleague at the Center for Strategic and International studies for a dozen years, is aware of the pro-American elites inside Russia, and he is at work creating for them a ‘China threat’ that they can use in their effort to lead Russia into the arms of the West. If this effort is successful, Russia’s sovereignty will be eroded exactly as has the sovereignty of every other country allied with the US.”

Already before Trump enters the White House, Beijing’s Xi Jinping is in greater conflict with Washington than at any time since China-US frictions of the early-2000s. On the other hand, US capital is extremely exposed in China through direct investment, supplier relations, R&D contracts and consumer markets. And Beijing still owns more than $1.3 trillion in Treasury Bills, although that holding has not increased since 2012.

Geopolitical tensions in the South China Sea began rising in 2011 with Obama’s “pivot to Asia.” This meant, according to journalist John Pilger, “that almost two-thirds of US naval forces would be transferred to Asia and the Pacific by 2020. Today, more than 400 American military bases encircle China with missiles, bombers, warships and, above all, nuclear weapons. From Australia north through the Pacific to Japan, Korea and across Eurasia to Afghanistan and India, the bases form, says one US strategist, ‘the perfect noose’.”

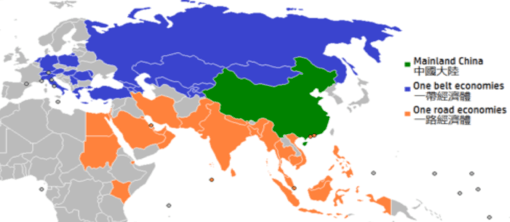

In addition, Eurasia is a testing ground because of increasing investments in Chinese infrastructure (perhaps amounting to $160 billion) in the former Silk Road – now ‘One Belt One Road’ – to be funded by the new Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), centering on Russian-Chinese energy cooperation.

Still, this picture of the BRICS and US imperialism remains fuzzy given Trump’s mercurial character, ruthless pragmatism, exceptionally thin skin, crude bullying behaviour and ability to polarise his own society and the world. Obama’s last moves as president include a few attempts to at least briefly Trump-proof his legacy: demonising Russia, banning oil drilling and opening new environmental reserves in vulnerable sites, condemning Israel’s West Bank colonisation, and protecting Planned Parenthood abortion facilities.

There is no question, though, that Trump’s most extreme threats to global geopolitics, economics, society and environment will be carried out by a Cabinet and lieutenants who represent the most regressive characteristics of US capitalism. Trump’s top layer of government can be termed ‘4G’, as it contains:

+ gazillionaires – his Cabinet is worth $15 billion, by far the most tycoon-infested in US history, including a top labour official opposed to a living wage;

+ generals – three veterans of the failed campaigns of Iraq and Afghanistan hold key security roles that had once been reserved for civilians;

+ gas-guzzlers – four lead officials in climate-related portfolios including the Secretary of State are loyal representatives of the oil, gas, coal and pipeline industries; and

+ GoldmanSachs – Trump’s Treasury Secretary, main economic advisor and lead political counsel were once executives of the Wall Street investment bank, responsible for so much global economic damage over the past decade due to predatory financing practices.

Must there be either an inter-imperialist conflict of elites that could lead to nuclear confrontation, debilitating trade wars or further juvenile insults as passions continue to rise on the one hand; or on the other, a new alliance of US and Russian elites that will codify a lucrative intra-imperial division of the world’s spoils including fossil-fuel exploitation and resulting climate change that will quickly spiral beyond repair?

The false hope of BRICS top-down resistance

One other option is a rational approach from the BRICS countries’ leaders. Reflecting how difficult this will be, however, former South African president Thabo Mbeki expressed Africa’s desire for a reformed United Nations when speaking directly to Putin in October last October: “The matter of the reform of the Security Council becomes important in that respect… It needs changing. It’s difficult. Russia is a permanent member that might be one of the obstacles to changing it, I don’t know.”

Neither Moscow nor Beijing will Brazil, India and South Africa for permanent seats (along with Japan and Germany), for fear of diluting their own Security Council power and especially their veto. The lack of space for Africa in the UN may mean, according to threats made by Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe in September, a formal boycott of the body by the continent starting in September 2017. And another vehicle for Third World advocacy, the Non-Aligned Movement, was considered increasingly irrelevant when in September 2016 Modi did not even show up at a Caracas summit, notwithstanding India’s formative role in its 1955 founding at Bandung.

Likewise, the BRICS leaders’ self-interest prevents genuine transformation of other multilateral institutions: in the last round of ‘reforms’ of the World Trade Organisation (WTO), International Monetary Fund (IMF) and UN Framework Convention on Climate Change – all consummated in December 2015 – there can be no question that Africa was the loser, as the BRICS’ neoliberal negotiators ran roughshod over the poorest countries.

Moreover, last August, the BRICS’ representatives at the Bretton Woods Institutions endorsed five-year contract extensions for World Bank and IMF leaders Jim Yong Kim (from the US) and Christine Lagarde (from France). They even confirmed Lagarde’s reign in mid-December the same day a Paris court found her guilty of criminal negligence when, serving as the French finance minister, she made a huge taxpayer payout to a tycoon who in 2007 had given financial support to her Conservative Party.

And hope for the BRICS Contingent Reserve Arrangement to serve as an emergency funding alternative to the IMF remains foiled by the provision that after borrowing 30% of the quota, a desperate debtor country must then get an IMF structural adjustment policy. And the BRICS New Development Bank’s potential role as an alternative to the World Bank appeared self-sabotaged last September when a cozy partnership was agreed that entails project co-financing and staff secondments.

In 2014, Obama agreed with The Economist editor interviewing him about “the key issue, whether China ends up inside that [multilateral financial] system or challenging it. That’s the really big issue of our times, I think.” He replied, “It is. And I think it’s important for the United States and Europe to continue to welcome China as a full partner in these international norms.”

The philosophy of subordinated incorporation – sub-imperialism for short – became too difficult for Obama himself to sustain, when in 2015 he dogmatically (and unsuccessfully) discouraged AIIB membership by fellow Western powers and the Bretton Woods Institutions. It was his most humiliating international defeat. But when it came to intensified trade liberalisation in the WTO, recapitalisation of the IMF under neoliberal rule, and destruction of the binding emissions reductions targets on Western powers that characterised the Kyoto Protocol, Obama’s strategy of bringing China and the other BRICS inside was much more successful.

In sum, looked at from above, the BRICS leaders regularly suffer status quo assimilation when it comes to global governance partnership, but they fracture when it comes to their own internecine competition or when failing to offer unified challenges to multilateral institutional leadership. And this inconsistency is what leaves the bloc wide open to a potential Trump wedge in 2017.

With this in mind, Immanuel Wallerstein argues that Trump “is using the Nixon technique in reverse. Nixon made a deal with China in order to weaken Russia. Trump is making a deal with Russia in order to weaken China.” Wallerstein doubts its efficacy simply because Beijing and Moscow are pursuing their own separate interests effectively already: “This policy seemed to work for Nixon. Will it work for Trump? I don’t think so, because the world of 2017 is quite different from the world of 1973.”

The main difference may be the more advanced stage of economic stagnation and desperation, a topic I will take up another time. But on the left, the kinds of dashed hopes so many activists harbored at that time are also worth recalling, for they included (sometimes in partial or very contradictory ways) sustained improvements in European social democracy and the US Great Society, rising Third World revolutions sometimes accompanied by Northern solidarity, the onward march of the Soviet Union and East Bloc, the Chinese “New Man,” the feminist and black power struggles, radical environmentalism, liberation of humanity from capitalist alienation and exploitation, the casting off of outmoded sexual mores and gender norms, and the end of statist domination.

Today, with the world’s progressive, democratic forces hunkering down on so many fronts, nevertheless a ripeness within so many societies’ resistance politics reflects a much broader, deeper capacity to link up than ever before: within the BRICS, the US and internationally. As Pilger concludes his recent film about Washington’s latest war-mongering (and as I will explore in the next essay), “We don’t have to accept the word of those who conjure up threats and false enemies to justify the business and profit of war. We have recognise there is another superpower, and that is us, ordinary people everywhere.”