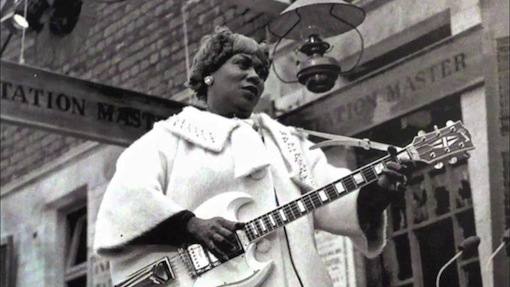

When Sister Rosetta Tharpe died in 1973, at the age of fifty-eight, she was buried in an unmarked grave outside of Philadelphia. Once, she had been the biggest star in gospel music. She was the first gospel artist to cross over to a pop audience, trading songs like “Nearer My God to Thee” for “I Want a Tall Skinny Papa,” much to the chagrin—and occasionally horror—of her more devout fans. Although she never strayed too far from her gospel roots (and embraced them later in life), she pioneered a sound that younger admirers, such as Chuck Berry and Elvis Presley, would mold into rock and roll. She was a woman who played the guitar, not just to accompany herself but as a lead instrument, and she ornamented her songs with flashy licks and intricate fingerpicking. That was rare for the time (and to some extent, still is). As countless people who’ve stumbled across footage of her performances on YouTube can attest, she could wail, and she made her guitar speak in tongues the way her sisters and brothers in the Sanctified Church sometimes seemed to do.

But at the time of her death, Sister Rosetta was, if not quite forgotten, certainly obscured. Mahalia Jackson was the acknowledged Queen of Gospel. Rock and roll, with a few exceptions, was a white man’s game. Younger audiences increasingly passed over gospel, blues, and early R&B for newer sounds. Some in the church never forgave Sister Rosetta’s dalliance with the devil’s music; some secular listeners never much appreciated the religious material to begin with. She had her fans, of course, but her reputation was dwindling. The writer and record producer Anthony Heilbut, who knew Sister Rosetta, points out in his book The Gospel Sound that three of the genre’s icons—Mahalia Jackson, Clara Ward, and Tharpe—all died within the space of two years. “Rosetta Tharpe may have died the most miserably,” he writes, “for the others departed like royalty, but her passing was scarcely noticed.” Her funeral at Bright Hope Baptist Church in Philadelphia was modestly attended. Once it was over, and the sounds of mourners and singers faded from the church, so too did her legacy begin its slow fade, year by year, through the remainder of the twentieth century.

It was as though the cultural memory couldn’t quite metabolize a figure like Sister Rosetta. Where in the story of rock and roll is there space for a black woman from a Pentecostal gospel background who played guitar and fused the sacred and the secular in her music? In an unmarked plot, apparently. And for decades, that’s where you would find Sister Rosetta Tharpe, if you bothered to look.

But there are strange things happening every day, as her song has it, and around the turn of the millennium, some strange things started happening. Sister Rosetta appeared on a U.S. postage stamp. A few years later, M.C. Records released a tribute album featuring the likes of Odetta, Bonnie Raitt, and Sweet Honey in the Rock. In 2007, the pop music scholar Gayle Wald published the first biography of Sister Rosetta, Shout, Sister, Shout. And one year after that, thanks to a benefit concert organized by a fan named Bob Merz, Rosetta Atkins Tharpe Morrison’s grave got a headstone. It reads “Gospel Music Legend” and bears an epitaph written by her friend Roxie Moore: “She would sing until you cried and then she would sing until you danced for joy. She helped to keep the church alive and the saints rejoicing.”

Today, one hundred years after her birth, Sister Rosetta is perhaps better known than at any time since the height of her fame. This is in no small part due to Wald’s book and the documentary The Godmother of Rock & Roll, created by Mick Csaky and broadcast by PBS in the American Masters series. She is better known, that is, compared to the decades when she was barely known. But undeserved obscurity is hard to shake, and admirers of Sister Rosetta know there is a whole lot of shaking left to be done.

But that’s alright.

She was born in Cotton Plant, Arkansas. Her parents, almost undoubtedly the descendants of slaves, worked in the cotton fields. They were a deeply religious couple, members of the Church of God in Christ, an offspring of the Pentecostal movement that was popular among poor and working-class black people, but often disparaged by the black middle class in their mainstream protestant churches. Despite its puritanism in some matters, the COGIC put music at the center of the religious experience, and Rosetta’s early life was alive with song. Her mother, Katie Harper (later Katie Bell Nubin), was a fervent evangelist who sang and played music in the church, and taught her daughter to do the same. Eventually, Katie Harper decided to leave Cotton Plant—and Rosetta’s father, Willis Atkins—to join the northward migration to Chicago, where she could start a new life and evangelize for the church. They ended up at Chicago’s largest COGIC congregation, on the city’s South Side, whose members referred to it simply as “Fortieth Street.”

Rosetta, all of six years old, began performing in earnest at Fortieth Street, and she amazed the congregants by singing and accompanying herself on piano and, especially, guitar. Soon, her mother took Rosetta out on the road, and the young girl left audiences enraptured all along the church circuit, revival by revival, congregation by congregation. This was a world hemmed in by segregation and racist terror, for sure, and the work must have been exhausting, but the church circuit was a bastion of black community and cultural expression, and a wellspring of affirmation for the righteous performer. Rosetta thrived on it. She learned to read the moods and expectations of a crowd, and how to calibrate the theatrical and seemingly “authentic” aspects of her performance. She could have scarcely known that she had begun a career of touring and performing that would continue for more than four decades.

By the late 1930s, Sister Rosetta was married to Thomas J. Tharpe, a COGIC preacher, and was building a reputation for herself as a gospel performer. Thomas Tharpe, it seems, enjoyed the publicity that Rosetta attracted—they toured together as a team—and otherwise lorded it over her in the worst patriarchal fashion. He was by many accounts a cruel and dishonest partner. It would have been easy, all too easy, for their marriage to grind on in the suffocating embrace of the church, with Sister Rosetta as the musical appendage to her husband’s sermonizing. But anyone who listens to her music will agree that there is something irrepressible about Sister Rosetta, a rebellious impulse that refuses to be smothered by convention. She left her husband and moved to New York City.

Sister Rosetta arrived in New York as something of a gospel ambassador, but it wasn’t long before secular material found its way into her sets, and she found her way onto secular stages. She performed at the segregated Cotton Club for elite whites and at the integrated Café Society for a more diverse and left-wing crowd. She was the first gospel singer to play the Apollo Theater in Harlem. In December of 1938, she performed in John Hammond’s legendary, Popular Front-tinged concert “From Spirituals to Swing” at Carnegie Hall. The New York Times was a touch condescending in its review of her performance, but nonetheless caught a sense of the transformation that was taking place: “Tharpe is as good as ever in combining jazz and religion without offending either, but Broadway seems to be tarnishing some of her backwoods musical innocence.”

She was no ignorant Holy Roller being seduced by the big city, as that reviewer suggested, but a woman seizing control, to the extent possible, of her life’s trajectory. “Rosetta Tharpe forged her own path, without a lot of guiding examples to help her on her way,” Gayle Wald, Sister Rosetta’s biographer, told me. “She enjoyed her fame and, although she had her share of troubles, resisted tragic narratives of her career and her life.”

If there was an element of tragedy in this portion of her career—aside from the daily humiliations and frustrations suffered by all black workers, cultural or otherwise, at the time—then it involved reactions from within the religious community, especially the Sanctified Church that nurtured her. Many saw Sister Rosetta’s new career path as worse than a sell-out; it was a betrayal and a surrender to worldly evils. “Swinging” the spirituals, as Sister Rosetta so wonderfully and enthusiastically did, was considered sacrilege—and for a spiritual performer to sing the blues or innuendo-laced pop songs was even worse. But that is precisely how Sister Rosetta made a name for herself. At certain times she implied that the decisions were out of her control—in particular, that she was contractually obligated to sing anything for the Lucky Millinder Band, and so had no choice but to perform songs like “I Want a Tall Skinny Papa.” But if you listen to any of these recordings, especially the swinging spirituals, there’s a certain undeniable exuberance that radiates through her singing and guitar playing. The message that comes across, all these decades later, is that Sister Rosetta was having a hell of a time. There’s little reason to doubt the sincerity of her religious belief—she spoke clearly and emphatically about her faith throughout her life—but that belief was entwined inextricably with her devotion to the music, which she played according to her own desires and attitudes, and not according to church doctrine.

Here’s an example. On Halloween, 1938, Sister Rosetta entered the studio to record her first four songs for Decca Records. One of them, “Rock Me,” was a re-working of the Thomas Dorsey gospel hymn “Hide Me in Thy Bosom.” As Gayle Wald points out in Shout, Sister, Shout, Sister Rosetta made some significant alterations to the original song. She had been performing it for years, and often stressed those two words—rock me—in her delivery. On the recording, however, she not only changed a word in the first line from “singing” to “swinging,” but held that “r” in “rrrrrrrock me” much longer than usual. In other words, she announced her intention to swing in the very first line of the song, and, as Wald puts it, embellished “rock me” in a way that “opens up the meaning of the phrase to various secular interpretations.” Truly, Sister Rosetta knew what she was doing, and even when she returned to singing gospel exclusively in the 1940s (and officially assumed the title “Sister” Rosetta Tharpe as a stage name), there was a kind of playfulness, and perhaps even irreverence, roiling beneath the surface of her music.

In September, 1944, Sister Rosetta recorded one of her greatest songs and biggest hits, “Strange Things Happening Every Day.” She was backed by a trio of Decca house musicians, including Sammy Price on piano, and they gave the gospel-inflected tune a boogie-woogie underpinning. It was a historic session. Seven years later, Jackie Brenston and His Delta Cats would record “Rocket 88,” which has assumed a place in pop mythology as possibly the first rock and roll song, if such a thing can be said to exist. But “Strange Things” is a significant precursor. In the evolutionary history of rock and roll, Sister Rosetta’s song is the fish who grew legs and gazed out from beneath the surface of the water at the beckoning land. Play the song today and you’ll find that it’s no fossil. “Like all great popular songs, it has an instant catchiness, as though it had always existed,” as Gayle Wald puts it, “and yet that catchiness, however ephemeral, is also durable, even profound.”

The lyrics, somewhat spare and a little cryptic, describe holy miracles while seeming to poke fun at religious hypocrites (“Oh, we hear church people say, They are in this holy way, There are strange things happening everyday”). But there is a critical posture inherent to the song that some listeners, especially black listeners, would have understood, and that continues to resonate today. In 1944 the United States was in the midst of a war against fascism, ostensibly to defend democratic rights and human equality. But Sister Rosetta, who often toured through the segregated South and confronted racist policies in the North, knew that the struggle against oppression only extended so far. For this reason she toured in her own sleeper bus to avoid dealing with segregated hotels. Even so, eating while on the road was difficult, and when she toured with the white gospel group the Jordanaires, whom she called her “little white babies,” they would often sneak meals back to the bus for her. Behind these mundane indignities, troubling enough on their own, was the constant threat of more serious harassment, or worse. All this in the Land of the Free—strange things indeed. Sister Rosetta’s personality is perhaps more present in this song than in any other—bemused throughout, joyful in moments, and yet charged with that subtle, critical attitude, the kind that only shows itself in the arch of an eyebrow or the certain shake of a head. No one would call this a protest song, but, like the best so-called protest music, it may cause listeners to stop and wonder about the world around them, and wonder how it might be different.

Sister Rosetta rode her fame into the 1950s but had passed the high point of her stardom, despite making a comfortable transition to the electric guitar. She continued to dwell within the conventions of gospel music while testing their boundaries and occasionally drifting outside of them completely, recording blues and other secular material. In the late 50s and into the 1960s, she began touring Europe and received the kind of rapturous appreciation that was increasingly hard to find in the United States. But she was in her last act.

In The Gospel Sound, Anthony Heilbut describes visiting Sister Rosetta at her home in Philadelphia, sometime around 1970. Not long after, she would suffer a stroke while on tour in Europe; a year later, one of her legs would be amputated, the result of diabetes; and by 1973, after a second stroke, she would be dead. But on that day, she looked back on the hard times she had suffered with a kind of melancholy wistfulness: “‘Someday I’m gonna write the story of my life, the people will cry and cry. I’ve been robbed, cheated, married three times, but God is so good—’ and Rosetta flashes her pinched, supersweet smile, letting out a characteristic ‘Oh yes.’”

She never wrote the story of her life, but the truths of it come through clear enough. Sister Rosetta faced her share of difficulties and tragedies—amplified, no doubt, by the fact that she was a black woman and an artist with the audacious idea that she ought to control the direction of her own life. She was devout, in her way, although she carried on affairs with men and some women, and was known to drink, curse, and otherwise cause her more uptight gospel companions to blush. The spiritual content of her music was real, as any belief is real to the believer, but it was also, as Marx put it long ago, “the sigh of the oppressed creature, the heart of a heartless world, and the soul of soulless conditions.” It was music for bearing burdens, and for making the burdens of others easier to bear.

But the music, and the pleasure of it, was also an end in itself. Consider Sister Rosetta’s third wedding, which remains, to this day, a remarkable and wonderfully strange event. The critic Greil Marcus called it “a classic American tall tale, except that it happened,” however hard to believe. In 1950, two gospel promoters, the brothers Irvin and Izzy Feld, staged a successful concert with Sister Rosetta at Griffith Stadium in Washington, DC. They wanted to top their success with another concert the following year, so they proposed a second performance—combined with a wedding. Sister Rosetta would be the bride. Not that she had anyone specific in mind to serve as the groom. But she signed a contract stipulating that she would find one in seven months, and eventually, she did. On July 3, 1951, at Griffith Stadium, she married Russell Morrison in front of twenty-thousand people. She wore a magnificent white wedding gown and played the electric guitar. The crowds loved it, but on that summer night, no one was likely more pleased by the spectacle than Sister Rosetta. (Except, perhaps, Russell Morrison, who became her manager and by most accounts proved to be yet another man freeloading off Sister Rosetta’s talent.)

Looking back, the wedding seems like a crude publicity stunt, and in many respects, it was. But isn’t there another way to see it? Imagine Sister Rosetta in the midst of that absurd scene, her wedding gown billowing, with fireworks blazing overhead and her amplifier ringing. “Get a load of this,” she might be thinking. “What a farce! But at least we’ll get an LP out of it—and a great concert!” The wedding was a means to an end, but the end was not Russell Morrison or a vow to any man. The vow was to her music, and the groom, in a sense, was incidental. It’s as though the ceremony was a declaration that Sister Rosetta would be wedded first and foremost to her musical career—to her fans, perhaps, and to herself—and that nothing else deserved her full and total devotion. For this act alone—ridiculous and defiant and inspiring all at once—she ought to be remembered.

She would be devoted to her music and nothing else, that is, except for God, although where God ended and music began for Sister Rosetta was never entirely clear. She couldn’t untangle that relationship in her lifetime, caught as she was between the expectations of the gospel world and the allure of the secular, and there is no point in trying to do it for her now. What’s clear is that Sister Rosetta Tharpe lived for her music, and today, one hundred years after her birth, it is the music that rings true, vital and thrilling as ever, proof that Sister Rosetta was a singular artist, never to be repeated. It doesn’t matter if you’re Sanctified or have some other religion or no religious belief at all—if you’ve suffered a little, or hoped a little, or have ever wanted to lie down and die, or have ever wanted to be free, then Sister Rosetta sings for you.

Scott Borchert has written about music and literature for Monthly Review, Southwest Review, The Rumpus, PopMatters, and elsewhere. He lives in New Jersey.