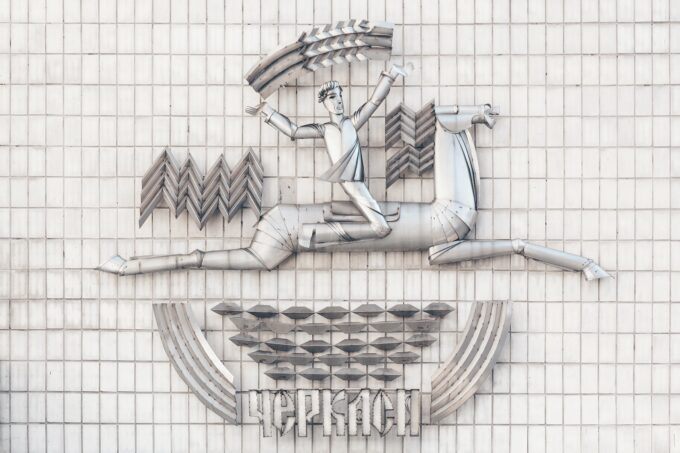

Image by Marjan Blan.

The reasons for the fall of the Soviet Union are myriad and can’t be laid solely at the feet of one person. Mikhail Gorbachev is widely despised by Russians as well as by activists and partisans of the Left. There are good reasons for that. It is impossible to imagine the collapse of a superpower and the catastrophic effects of imposing capitalism via “shock therapy” that immiserated a vast country without him.

But if we are serious about analyzing history, and the ongoing effects that history has on the present day, we must take a dialectic approach, and examine this history in all its complexities. Amid the triumphalist accolades heaped upon Gorbachev upon his death from Western capitalists and the opprobrium heaped on upon him by his many critics — continuing a pattern of three decades since the Soviet Union’s dissolution at the end of 1991 — we might take a more nuanced view.

The preceding is not to deny that Gorbachev was, ultimately, a failure who disorganized an economy and set in motion one of the greatest economic collapses ever recorded. But to pin all blame on him ignores not only other personalities but the stultifying effects of an economy badly in need of modernization and democratization, a sclerotic political system and the social forces and corruption set in motion during the reign of Leonid Brezhnev. Nor would it be fair to exclude the unrelenting pressure put on the Soviet Union and other countries calling themselves “socialist” that did much to distort and undermine those societies.

Nonetheless, a serious examination must concentrate on internal factors, those the responsibility of Gorbachev, and those where responsibility lies elsewhere. That was the approach taken in my book It’s Not Over: Learning From the Socialist Experiment, and it is that book’s fifth chapter, The Dissolution of the Soviet Union — that forms the basis of this article. Indeed, the mounting problems of the Soviet Union were not unnoticed within its borders — from the 1960s, academic institutions published reports detailing the bottlenecks built into the system and reform plans were drawn up within the government, but mostly were ignored.

The edifice of the Soviet Union was something akin to a statue undermined by water freezing inside it; it appears strong on the outside until the tipping point when the ice suddenly breaks it apart from within. The “ice” here were black marketeers; networks of people who used connections to obtain supplies for official and illegal operations; and the managers of enterprises who grabbed their operations for themselves. Soviet bureaucrats eventually began to privatize the economy for their own benefit; party officials, for all their desire to find a way out of a deep crisis, lacked firm ideas and direction; and Soviet working people, discouraged by experiencing the reforms as coming at their expense and exhausted by perpetual struggle, were unable to intervene.

Five years of reform with meager positive results in essence caused Gorbachev to throw in the towel and begin to introduce elements of capitalism. Gorbachev intended neither to institute capitalism nor bring down the Soviet system, but by introducing those elements of capitalism, the dense network of ties that had bound it together unraveled, hastening the end. To say this, however, is not at all to agree with some simplistic and unrealistic ideas out there that Gorbachev was a trojan horse intent on destruction. Every so often, over a period of many years, an article circulates online purporting to quote Gorbachev that he was intent on destroying the Soviet Union from the beginning of his career and worked patiently until he was in a position to do so. But this “confession” has allegedly appeared in many different publications in several different countries. The last time I saw this peddled it was an alleged article published in a Turkish newspaper. One might ask: Why would he make a spectacular confession such as this to an obscure publication in Turkey?

People who circulate such nonsense are simply seeking a scapegoat, and either can’t be bothered to study the actual conditions of the Soviet Union or are so blinded by a rigid ideology that they have ceased thinking. Again, this in no way suggests Gorbachev doesn’t have a huge responsibility to history. One can be a firm critic of the Soviet Union and still lament what happened.

Changes needed, but what changes?

Serious reforms were necessary; that is why the members of the Politburo, the Communist Party of the Soviet Union’s highest body, finally named Gorbachev general secretary. There was also strong support for his elevation among the party’s regional and provincial first secretaries, who formed the backbone of the Central Committee. When Andrei Gromyko, the foreign minister for a quarter-century and stalwart of the party’s old guard, endorsed Gorbachev’s ascension, that essentially clinched the promotion. Reforms had been attempted since 1965, when Prime Minister Aleksei Kosygin first proposed reforms that went nowhere. But by 1985, even the most doctrinaire party leader knew changes were necessary. The political and economic systems were out of date. A Soviet book published 20 years earlier declared that “a system which is so harnessed from top to bottom will fetter technological and social development; and it will break down sooner or later under the pressure of the real processes of economic life.”

Gorbachev started by stressing the “strengthening of discipline,” cracked down on alcohol, readily discussed the need for improvements in consumer products and consolidated several ministries to retool industry. He also pushed out several high-ranking officials opposed to any reforms, demanded “collectivity of work” in all organizations and declared that collective work is a “reliable guarantee against the adoption of volitional, subjective decisions, manifestations of the cult of personality, and infringements of Leninist norms of party life.”

Even before he became general secretary, Gorbachev had begun meeting with intellectuals working in Soviet institutions, later recalling that his safe was “clogged” with proposals. “People were clamoring that everything needed to be changed, but from different angles; some were for scientific and technical progress, others for reforming the structure of politics, and others still for new organizational forms in industry and agriculture. In short, from all angles there were cries from the heart that affairs could no longer be allowed to go on in the old way.”

First major reform more stick than carrot

Yet when it came to making concrete changes, there was a lack of imagination. To put it bluntly, Gorbachev had no plan and little idea of what to do. So when concrete structural changes began being implemented in 1987, they mostly were on the backs of working people. Eventually, the early enthusiasm for a new course gave way to anger and disillusionment. The first major reform, the Law on State Enterprises, approved in June 1987 by the party Central Committee, was more stick than carrot. The basic concept of the enterprise law was to liberate enterprises from some of the more rigid controls of the ministries, put them on profit-and-loss accounting, reduce the amount of product required to be produced for the state plan, reduce subsidies in order to make enterprises more efficient, and to bring a measure of democracy into the workplace with the creation of “labor-collective councils” and workforce elections of enterprise directors.

State planning remained in force, but would become less of a hard numerical total and more of a guide, although the requirement of fulfilling the (reduced) plan requirements would continue. Production sold to the state under the plan would still constitute most sales and would continue to be paid at rates specified by the state, but production beyond plan fulfillment could be sold at any price, subject to volume limitations to prevent unnecessary production beyond any reasonable social need.

In conjunction with these reforms, measures were implemented aimed at putting pressure on wages. Basic wage rates were increased, but individual output quotas (or “norms”) were also raised, to make it much more difficult to earn bonuses. Bonuses would no longer be essentially automatic; they could only be earned through more effort — and the new wage levels made up only part of the differences between the new basic wage and the old basic wage plus bonus. Put plainly, workers would have to work harder to earn the same amount of money. The basic idea behind these sets of reforms was to introduce a mechanism that would provide a better understanding of demand while retaining central planning. In turn, more efficiency would be wrung out of the system through the use of shop-floor and enterprise-wide incentives and the introduction of some workplace democracy, thereby alleviating both some of the alienation on the part of the workforce and the incentive of management to avoid introducing technological or other improvements.

The de facto wage cuts, and accompanying ability of factory managers to force workers into lower skill grades (thereby forcing reductions in wages), was implemented immediately, but the rest was to be phased in. “Labor-collective councils” were supposed to be formed to give workers a say in managing their workplace since they were asked to shoulder some of the profit-and-loss responsibility. These were stillborn. In most factories, either there was no council, it did nothing or the enterprise director headed it, neutralizing its potential. The trade unions, as before, did nothing to intervene, remaining silent or backing management.

The enterprise law text was ambiguous — it made references to “one-man management,” the foundation of the existing top-down command structure; did not specify the powers of labor-collective councils and the workforce; and stated that, although directors are elected, those elections must be confirmed by a ministry, a veto power supposedly needed to avoid cases of unspecified excesses. Not only did managements remain unanswerable to workforces, government ministries refused to relinquish their grips. Government bureaucrats owed their privileges and power to the ability to command, and naturally most of them did not relish losing such positions. Ministry officials continued to issue detailed orders to enterprise managements that left no room for enterprises to make their own decisions and continued to require enterprises to buy from a specific supplier, acting as a crucial brake on democratization; they also continued to impose management personnel. The traditional top-down economic structure remained largely untouched.

Workers announce their response by striking

During these years, serious reforms to the structure of the Communist Party were made, with Gorbachev maintaining his hold on power and steadily placing his followers into high-level positions. There may have been a quickening pace of events in the political sphere during 1988 and 1989, but everyday matters such as the economy and living standards stagnated. Failing to see sufficient improvement from the promises of perestroika, working people began to take a more direct approach — by striking.

The first mass strike was conducted by the country’s miners in 1989. More than 400,000 miners ultimately walked out across the country. The fastest advancing strikers were in Ukraine’s Donetsk province. Strikers there occupied the square in front of the regional party headquarters, and all 21 area mines sent representatives to occupation meetings. Abandoned by their union and all other institutions, the miners set up their own strike committee, and began making contact with the striking miners in other regions, who then also set up committees. The strike committees became the effective local governments, setting up patrols, acting as arbitrators for problems citizens brought to them and closing all sources of alcohol. Strikers this time refused to negotiate with the coal industry minister, and would only end the strike when Prime Minister Nikolai Ryzhkov signed a detailed agreement and Gorbachev announced his personal approval.

Further strikes in other industries broke out. These were often strictly local affairs, however, and there was little attempt at national coordination, rendering them politically ineffective. Nor was there coordination with the miners. The Soviet trade union central umbrella was widely seen as irrelevant, but new unions that began to form by 1990 were very small and unorganized, and even the very few unions that did work well had no links with other unions. A lack of a coherent plan and a lack of grassroots pressure meant that perestroika, as the restructuring was called in Russian, was failing.

All social groups seemed to lose faith in perestroika. By 1990, polling found that 85 percent believed that economic reform had achieved nothing or made the situation worse. As the miners’ strike, the failure of the labor-collective councils and mounting disillusionment demonstrated, efforts by the reformers to gain the support of working people had failed. Two important reasons for this failure were the ongoing shortages of consumer goods, which, if anything, were becoming worse, and the realization that the economic reforms were, in large part, going to come on their backs. The timid effort at workplace democratization through the labor-collective councils was intended to compensate people on the shop floors for the harsher work conditions and lower basic pay, and when the councils proved a farce the reformers were empty-handed.

The 1987 enterprise law, in addition to the profit-and-loss accounting and its other reforms, also legalized “cooperative” retail and service enterprises. These cooperatives, although not altogether new, helped exacerbate shortages and trigger inflation. Farmers’ markets, which sold produce at higher prices than charged in state markets while offering greater variety, were long a part of Soviet retail, as was street trading and peddling. But the new cooperatives quickly took advantage of the differential between what the new market would bear and the level of prices set in state shops. For example, when a shipment of meat would arrive at a state store, where it was intended to be sold at the low, state-controlled price, more than half of the shipment would be illicitly resold to a cooperative, which would then sell it at a far higher price, and leaving a shortage in the state store.

Another report found that, although the Soviet Union enjoyed an excellent harvest in 1990, only 58 percent of produce that was supposed to be delivered to state stores actually made it; the remainder was siphoned off by black marketeers or rotted due to a distribution system that was breaking down. Consumers feared future shortages, which became self-fulfilling prophecies when wide-spread hoarding helped empty store shelves.

Why manage factories when you can own?

By now, black marketeering and corruption, which blossomed during the Brezhnev “era of stagnation,” were worse than ever. Now adding to the picture was that the government and industrial bureaucracy (known as the “nomenklatura”) had begun thinking bigger. Their privileges were based on their management of the Soviet Union’s industry and commerce, and this control rested completely on the state ownership of that property because they did not own the means of production themselves.

Some among the nomenklatura began to dream of capitalism — then they would be able to dramatically upgrade their lifestyle. Economic malaise was becoming more pervasive as the dense web of threads that held the Soviet system together were starting to be snipped through corruption, local protectionism and supply disruptions, the last of which was exacerbated because many component parts were produced in only one factory. The move to profit-and-loss accounting helped to bring about an “all against all” mentality: Instead of simply continuing to manage state property, why not grab it for yourself?

It was against these backdrops that in 1990 Gorbachev began to abandon his efforts to renew the system he inherited. On the political level, the general secretary began eliminating the party’s monopoly on power and, through creating a new freely elected legislature, built himself a power base outside the party. His power was soon used to begin to introduce elements of capitalism. To bring about these “market reforms,” the limited ability of working people to defend themselves had to be eliminated. A series of laws designed to do this began with a new enterprise law stealthily passed by the Supreme Soviet in June 1990. Gorbachev continued to insist that market reforms were to remain within the boundaries of a socialist system (and there was a widespread belief in the country that the conditions for an outright restoration of capitalism didn’t exist), but in reality from this time the debate within Gorbachev’s government and among his closest advisers was about how far and how fast the transition to a capitalist-type system should go.

The new law eliminated what little opportunity workers had to influence their management in addition to legalizing private ownership of enterprises. More would quickly come in the following months. Subsequent laws completely freed wages of any central control, reducing wage labor to a commodity as it is in capitalist countries; granted guarantees to investors, including compensation in the event that future legislation affects an investment; created unemployment insurance but failed to authorize any money to pay for it, in expectation of mass unemployment; and legalized the privatization of state enterprises.

Simultaneous with the passages of the above legislation, two competing economic plans were floated. One called for a phase-in of some market mechanisms over five years while retaining state control over pricing, the other called for a sweeping transition to a capitalist economy in 500 days with no working plan on how to accomplish that. Gorbachev, increasingly unable to make a decision, asked the backers of the competing plans to reach a compromise between them. But Boris Yeltsin, having maneuvered himself into the newly created presidency of the Russian Republic, undercut Gorbachev by unilaterally declaring the 500-day plan adopted.

The Russian Republic constituted about 80 percent of the area of the Soviet Union and was by far the dominant republic among the Soviet Union’s 15 republics. The other, much smaller 14 republics had their own party apparatus, albeit completely subordinate to Moscow, and a Russian republic party would have been almost redundant. But as nationalism rapidly gripped peoples across the country, a Russian party body was created. Yeltsin gained control of it, using it to accelerate and deepen a path toward capitalism, undermine Gorbachev, dismantle the Soviet Union and ultimately impose brutal shock therapy on Russians after the Soviet Union’s dissolution.

In essence, Yeltsin set up a dual government in competition with the Soviet government headed by Gorbachev. But unlike 1917, when a brief period of dual government would end with the taking of power by the Bolsheviks, this time the capitalist restorationists led by Yeltsin would win.

The period of a dual government must always be brief

As 1990 drew to a close, many reformers became convinced that Gorbachev had gotten cold feet, and would call a halt to reform or even turn back. His appointment of hard-liners as prime minister (Valentin Pavlov), interior minister (Boris Pugo) and vice president (Gennadii Yanayev) fueled this fear; enough so that Gorbachev’s long-time ally and foreign minister, Eduard Shevardnadze, resigned in December with a warning that “dictatorship is coming.” Ironically, hard-liners — those who had been opposed to any reforms and wanted a return to the Brezhnev era — were needed so that capitalism could be imposed on a country that didn’t want it.

Gorbachev, until the end, maintained that he was committed to a long-term strengthening of socialism through the introduction of market mechanisms, although the concrete results of the decisions that he and the Supreme Soviet took from June 1990 formed a reality of a phased transition to capitalism. Yeltsin, in contrast to his populist image and public proclamations in favor of democracy, stood firmly for a much more rapid transition to capitalism — when the time came, the change would be so sudden and so cruel it would become known as “shock therapy.” Yeltsin was already assembling a team of young technocrats itching to upend the entire economy, and there would be absolutely no popular consultation nor any consideration of the social cost. Yeltsin was also a skilled political tactician; he turned back an attempt by the Russian parliament to remove him as parliament chair by calling for demonstrations in his support and gathering enough support so that a referendum to create a new post of Russian president be put to voters. Voters approved, and in June 1991 Yeltsin was elected president of the Russian republic. The dual government was more firmly in place.

Separate from all the political maneuvering, no true popular mass movement developed. If the creation of a better society, with popular control over all aspects of life, including the workplace, was in a position to happen, it was now, before widespread privatization. The workers of Czechoslovakia, during the Prague Spring, had begun working out a national system of workers’ control and self-management; they could attempt to create an economic democracy because the economy was in the hands of the state, and therefore could be placed in collective hands under popular control. But once the means of production become private property, the task of wresting control becomes vastly more difficult. The owners of that privatized production dominate a capitalist economy, enabling the accumulation of wealth and wielding that wealth to decisively influence government policy; the state becomes an agent of the dominant bourgeois class and the force available to the state is used to reinforce that dominance.

Although it probably is impossible to overstate the exhaustion of Soviet society as a factor in the failure to develop national grassroots organizations, perhaps the people of the Soviet Union didn’t believe that they had nothing left to lose as their ancestors had in 1917. Back then, Russians lived in miserable material conditions and under the constant threat of government violence. By no means were material conditions satisfactory during perestroika, but they were not comparable to the wretchedness endured under tsarist absolutism nor did the urgency of having to remove a violent dictatorship exist. A social safety net, tattered and weakened, still existed, and most Russians believed that, despite whatever dramatic economic and political changes still lay ahead, they would be able to retain the social safety net they were used to under Communist Party rule.

Pushing back against economic and political changes, hard-liners thought they would be able to turn the clock back and reinstitute some variation of the orthodox Soviet system. They, too, did not understand the social forces that were gathering. The Soviet Union could not stand still — if it could not find a path forward to a pluralistic, democratic socialist society that would be defended from across the country, then capitalism was poised to burst in as if a dam holding back a sea burst.

The Soviet Union could not find such a path — working people were unable to create a society-wide movement, perestroika was unable to solve the massive economic problems that had only become worse, and introducing capitalistic reforms had severed the supply and distribution links among enterprises without putting anything in their place. The Soviet command system did not function well and had been long overdue for radical changes to convert it into a more modern system — but it did function. What had begun to replace it, elements of capitalism, disorganized the country’s economy into disaster.

Yeltsin grabs power and imposes shock therapy

The August 1991 putsch brought an end to communist rule. Although the coup was badly executed and failed within three days, with Gorbachev reinstalled as Soviet president, the failure of the party to condemn the coup and Yeltsin’s opportunistic speeches loudly condemning the coup, despite his antipathy toward Gorbachev, meant that Yeltsin emerged as the winner. The party was swiftly banned, its publications suspended, and the brief period of the dual government effectively ended. Yeltsin quickly assembled a team of young technocrats itching to dismantle all institutions of planning and began doing so despite having no legal authority to alter Soviet agencies. That no longer mattered; Gorbachev was now irrelevant. He resigned at the end of the year, having no country to lead.

The three leaders of the Slavic republics — Yeltsin, Leonid Kravchuk of Ukraine and Stanislav Shushkevich of Belarus — met in a forest to sign an accord declaring that the Soviet Union had ceased to exist. One week after Mikhail Gorbachev’s resignation, the shock therapy would begin on January 2, 1992, with complete liberation of prices (except for energy), the concomitant ending of all subsidies of consumer products and for industry, and allowing the ruble to float against international currencies instead of having a fixed exchange rate. The strategy was to radically reduce demand, a devastating hardship considering that most products were in short supply already. The freeing of prices meant that the cost of consumer items, including food, would skyrocket, and the ruble’s value would collapse because the fixed value given it by the Soviet government was judged as artificially high by international currency traders. This combination would mean instant hyper-inflation.

Yeltsin was already ruling by decree at the end of 1991, and his team of reformers used the president’s authority to force through their plans. Inflation for 1992 was 2,600 percent and for 1993 was nearly 1,000 percent — that alone wiped out all savings held in banks. The excess cash that had accumulated in banks, instead of being put back into circulation by stimulating demand or used toward productive investment, was simply made worthless. A large surplus of personal savings parked in banks had built up during the previous three years because there had not been enough production for consumers to buy. Yeltsin’s economic aide, Yegor Gaidar, considered liquidation of the money in savings accounts part of the effort to reduce Russia’s “monetary hangover.” In other words, Russians possessed too much money — another “technical” issue because too large a supply of money causes inflation, Chicago School economists believe, a problem cured here through hyper-inflation.

In the first days of January, what little food was available in state stores completely disappeared, as state-store managers diverted their supplies to private operators for a cut of their profits. State enterprises were also crippled by new high taxes levied only against them. Reduced to penury, Russians took to the streets to begin peddling their personal possessions to survive. At the same time, a handful of speculators, mostly arising out of black-market networks, made fortunes through smuggling consumer items and exporting oil, the latter particularly lucrative because the oil was bought at extremely low subsidized Soviet prices and sold abroad at international market prices. Organized crime networks blossomed, demanding “protection” money from all merchants and street peddlers.

Yeltsin would, in 1993, maintain power by launching a military assault on parliament that killed about 500 people and wounded another 1,000. Yeltsin ordered the parliament disbanded and, for good measure, also disbanded the Moscow city council. He was loudly applauded by the U.S. government and financial institutions for preserving democracy for that. Yeltsin would go on to give away Russia’s natural resources to oligarchs who had him re-elected in 1996 despite an approval rating of 3 percent.

Further economic disasters would come. By the end of 1998, on the heels of another crash that again wiped out savings, Russia’s economy had contracted 45 percent from 1990, when capitalism began to be introduced. Investment in industry declined by almost 80 percent in the same period and the murder rate skyrocketed to become one of the world’s highest. Two million children were orphaned with more than half of them homeless. The World Bank estimated that 74 million Russians lived in poverty; two million had been in poverty in 1989. In the Ural Mountains, competing organized-crime groups fought armed battles for control of factory complexes, backed by different police forces, with the winners then proceeding to strip the assets.

The stagnation of Gorbachev gave way to collapse under Yeltsin. Capitalism de-developed Russia. The weakness of Russian institutions, both cause and effect of the oligarchs, had the perverse effect of enabling a vigorous proponent of nationalism, Vladimir Putin, to arise. How much of Russian history can we assign to Mikhail Gorbachev? A lot. But not all. History is always far more complicated than the career of one human being. What if the Soviet peoples had rallied to their cause and built a system of economic democracy? History would be far different. Gorbachev must be assigned much responsibility for the inability of Soviet peoples to organize, but the long history of Soviet-style communism that atomized and alienated people while shutting them out of political participation can’t be overlooked, nor can the Soviet bureaucracy’s willingness to adopt capitalism for personal enrichment be overestimated.

There was a poverty of imagination: In a mirror of the West, Soviet officials could not see beyond an impoverished and unimaginative choice of either Soviet-style centralism or Chicago School runaway capitalism. No one leader could, or can, be responsible for all that.