Montana’s Bitterroot National Forest is proposing the Bitterroot Front Project (BFP), encompassing 144,000 acres. This action will impact an area more than four times the size of the 34,000-acre Rattlesnake Wilderness north of Missoula.

The Bitterroot Front Project (BFP), the agency says, will promote “forest restoration” and reduce tree mortality from disease, insects, and fires. The way to accomplish this is through chainsaw medicine. Unfortunately, the proposal is based upon flawed assumptions and misguided policies.

Here’s a link to a video produced by the Forest Service to rationalize more logging. The video promotes a lot of misinformation about wildfire. In this video it claims today’s forests are much denser than historic conditions due to fire suppression and other factors. However, that view is challenged by some scientists arguing that the methods used to deduct forest density are flawed.

The agency implies fewer trees are killed in areas with substantial logging, but it never counts the trees it kills with chainsaws. Recent studies suggest that more total trees are destroyed by thinning and fire than from fires alone if you include all the trees removed by chainsaw medicine.

The snags resulting from a large blaze store carbon for decades, not to mention the charcoal in the soil, and roots, all of which also store carbon. There are still snags from the 1910 Great Burn surviving and storing carbon more than a hundred years after this 3.5 million acre blaze.

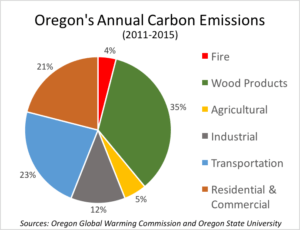

By contrast, logging and wood processing releases carbon immediately (i.e., climate-warming gases) into the atmosphere. Logging releases three times the carbon as a wildfire on a per-acre basis and ten times the carbon of wildfire and insects combined. By contrast, wildfires release a relatively small amount of carbon.

For instance, in Oregon, the most significant contributor to greenhouse gas emissions in the state is the result of logging.

When the agency claims it will reduce wildfire by logging, it’s ignoring the best science that shows that active forest management INCREASES fire spread under extreme fire weather conditions. Another study “found forests with higher levels of protection had lower severity values even though they are generally identified as having the highest overall levels of biomass and fuel loading.” In other words, logging forests actually promotes severe wildfires.

Why? Because when you open the forest through logging, it often promotes the regrowth of grasses, shrubs, and other fine fuels that sustain blazes. The lack of shade permits fine fuels to dry out, making them easy to ignite. Also, the open forest allows more wind penetration which favors fire spread.

The wind is the primary factor in fire spread, with 90% of the burning occurring during periods of high winds. And wind’s ability to spread and enhance fire spread is not linear; instead, it is exponential. In other words, a 20 mile an hour wind doesn’t just double fire spread over a 10-mile breeze but quadruples it. So you can imagine what a 50-60 mph wind can do.

Without wind, you don’t get much fire advance. But with wind, embers are tossed often a mile or more ahead of the fire front, starting new ignition zones. Lofting of embers by wind is why thinning, logging, and other “active forest management” fails to halt significant blazes.

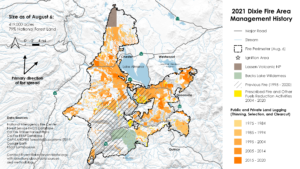

Map of California’s Dixie Fire which charred nearly 1 million acres in 2021 overlain by past “active forest management” colored orange showing that extensive thinning and logging did not preclude the Dixie Fire’s spread, and may have exacerbated fire spread. Map Bryant Baker.

For instance, both the Dixie Fire, which burned nearly a million acres, and the 400,000 acres plus Bootleg Blaze in Oregon raced through forests where as much as 75% of the land had been “treated” with active forest management—i.e., chainsaw medicine.

Even prescribed burning is relatively ineffective when confronted by a wildfire driven by extreme fire weather. One critique characterized prescribed burning effectiveness as a watering can that pretends to be a river.

Furthermore, the FS implies that high severity fires where most trees are killed are somehow undesirable. Yet, more wildlife species are dependent on the snag forests that result from these blazes than the low-severity ignitions they suggest are desirable.

However, many plants and animals live in the “fear” of green forests.

The snag forests that result from high severity blazes will have more bees, more butterflies, more fungi, more birds, more flowers, more fish, more bats, and more food for large animals like elk and deer. Some studies suggest the second-highest biodiversity found in a forest ecosystem is the snag forests resulting from high severity burns.

That is why chainsaw medicine degrades rather than ‘restores” forest ecosystems. The problem with most Forest Service employees is they cannot see the forest (ecosystem) through the trees. Dead trees are critical to a healthy forest ecosystem.

We are now amid the worse drought conditions in 1200 years. Does anyone think this isn’t the major factor driving large blazes? The idea that you can “restore” the forest to its “historic” condition is delusional. Those historic conditions do not exist anymore.

The warming climate is creating conditions that favor large blazes. I can guarantee if, by some luck, the climate were to suddenly return to another Little Ice Age, we would see few fires, no matter how much “fuel” (I call it wildlife habitat) was found in the Bitterroot forests.

To protect homes, start at the house and work outwards. Reduce the flammability of the home ignition zone. But treating the forest more than a hundred feet from homes provides no additional benefit and only degrades our forest ecosystems.

In promoting chainsaw medicine, the Forest Service is like the old-time Snake Oil salesman who promoted magical elixirs to cure all ailments. Chainsaw medicine is today’s snake oil. Don’t buy it.

If you wish to comment, here’s a link.