I have to say that I was surprised and disappointed by the data in the January Consumer Price Index. I expected to see evidence that some of the sharp runups in the prices of items like cars, clothes, and appliances were starting to be reversed. The idea was that the main factor in these runups was not higher costs of production, but shipping problems, which were being alleviated.

The basis for the belief that shipping problems were being fixed was both anecdotal accounts in the media and also the big increases in retail inventories reported for December. It seems stores had ordered (and received) lots of stuff they couldn’t sell. This is a context in which we might normally expect prices to fall, or at least not rise further.

That turned out not to be the case. The price index for appliances rose 1.5 percent in January and is now 8.5 percent above its year ago level. The index for apparel rose 1.1 percent in the month putting it 5.3 percent above its year ago level. And, used vehicle prices rose 1.5 percent in January, and are now 40.5 percent above year ago levels. So, there is not much of a story of a turnaround there.

There was also a lot of inflation in items not directly connected to the supply chain. Prescription drug prices jumped 1.3 percent, after being pretty much flat the prior year.[1] The health care insurance index, which measures the operating costs and profits of the industry, rose 2.7 percent, the fourth consecutive month with a rise in excess of 1.0 percent. This follows thirteen consecutive months of declines. And rental inflation appears to be accelerating, with the rent proper index rising 0.5 percent and owners’ equivalent rent going up 0.4 percent in the month.

All in all, this is not a good story. Still there were some positive signs. New car prices were flat in January, suggesting that supply may finally have caught up with demand in the sector. They are still up 12.2 percent over the year. The index for rental cars fell 7.0 percent in January, following a 2.7 percent drop the prior month. This indicates that rental companies have managed to rebuild their fleets and will not be an outsized source of demand for new cars going forward. The index still has a way to drop, it is 29.3 percent above its year ago level.

Also, television prices, which I have treated as a canary in the coal mine, fell another 1.4 percent, their fifth consecutive monthly decline. This mostly reverses a 12.0 percent run-up in television prices between March and August, although they are still 2.4 percent above year ago levels. My expectation is that the price of cars, and many other items, in the months ahead will look a lot like television prices, dropping back to levels that are comparable to where they were before the pandemic.

I’ve been saying that for several months now and it has not yet happened. I still think it will, but we shall see. In the meantime, I want to make three points about the inflation we have been seeing to date:

+ Most people are almost certainly enjoying better living standards than they did before the pandemic, ignoring of course the pandemic itself. In other words, the tales of serious deprivation being seen in the media, while undoubtedly true for many families, are not worse or more frequent than what they would have found in 2019, if they had chosen to look.

+ This inflation, unlike the 1970s inflation, is clearly profit driven, not wage driven. While we could end up with the sort of wage-price spiral we saw in the 1970s, we are not there presently. Businesses have raised prices in response to temporary (hopefully) shortages, which has led to higher profits. These profits can fall back if workers regain their income share.

+ There has been an uptick in productivity growth in the last few years. This is in contrast to the 1970s which saw a sharp slowing in productivity growth. This can allow for both higher real wages and higher profits.

Have Living Standards Improved?

Most people get most of their income through wages. This would seem to imply that we just need to look at the pattern in real wages over the last year to determine whether people are better off. However, the circumstances of the pandemic make this more difficult than would usually be the case.

The data for the last year are distorted by two factors directly attributable to the pandemic. The first is a composition effect. In 2020 millions of people lost their jobs. The job losers were concentrated at the lower end of the pay scale, which meant that average wages rose simply due to a composition effect. The average wage of the people who still had jobs in 2020 was higher than the average wage of people who were working in 2019.

In 2021 this composition effect was reversed, with most lower-paid workers getting their jobs back. This lowered the average wage in 2021.

There was also a pandemic price effect. The price of many items, most notably gasoline, fell in 2020 as the recession led to a drop in demand. This was reversed in 2021 as the U.S. and world economy grew rapidly.

For these reasons, taking real wage growth in 2021 in isolation gives a misleading picture of wage growth. The more honest route would be to combine the two years and compare real wages today to where they were two years ago. (I know this overlaps presidential terms, but such is life.)

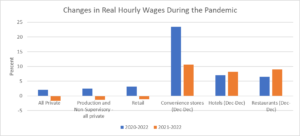

The real average hourly wage has risen by 2.1 percent compared to its January, 2020 level. (It fell 1.7 percent in the last year.) This means that a typical worker’s pay will go 2.1 percent further now than it did in 2020. If most workers were not suffering severe deprivation at the start of 2020, it is not reasonable to claim that they are today.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Furthermore, the wage gains look better at points lower down the wage ladder. If we look at the average hourly wage for production and non-supervisory workers, a group that excludes most professionals and managers, it rose by 2.5 over the last two years, after adjusting for inflation. For production and non-supervisory workers in retail, the gain in real wage was 3.2 percent over the last two years.

If we look at the lowest paying sectors, workers secured real wage gains even in 2021. Production and non-supervisory workers in convenience stores had a 10.6 gain in real wages during 2021. In hotels workers had a real wage increase of 8.2 percent over the year, and in restaurants the gain was 9.0 percent.

In short, workers at the lower end of the pay scale have generally been doing well the last two years, in spite of the uptick in inflation. It is also worth noting that many have seen their income increase over the last two years due to the various government payments over this period.

In 2020 and 2021, the government sent out a total of $3,200 per person in pandemic checks to the vast majority of adults, with additional payments for dependent children. Unemployed workers received $600 supplements to their unemployment checks for the months from April of 2020 to August of 2020. They then got supplements of $300 per week from January of 2021 until September of last year. As a result of these supplements, many lower paid workers were receiving as much or more in unemployment benefits as they did when they were working.

The American Recovery Act also included an increase in the child tax credit to $3,000 per child and $3,500 for children under age six. Also, unlike the prior tax credit, this benefit was fully refundable, so even the lowest income family could receive the full benefit of the tax credit. While this program expired at the end of 2021, it did put additional money in the pockets of the families who most needed it.

The general structure of the pandemic relief programs was quite progressive. A $1,200 check means much more to someone earning $20,000 a year, than to someone earning $100,000. The same is the case for the expansion of the child tax credit. As a result of these benefits, and the sharp rise in real wages for those at the bottom, lower income households had far more money in their bank accounts during the pandemic than they had previously.

While middle and higher-income households may have benefitted less from these pandemic payments, and seen smaller gains in real wages, they are also likely doing better in most cases than before the pandemic. Close to ten million people have taken advantage in the plunge in mortgage interest rates to refinance their mortgages, saving an average of more than $2,800 a year in interest payments. This is a substantial savings for a family earning $100,000 a year.

In addition, higher income households were much more likely to benefit from increased opportunities to work from home. The increase in remote work has allowed for tens of billions of in savings from lower commuting costs, dry-cleaning bills, and other work-related expenses. These savings do not appear in the data as a decrease in the cost of living, but if a worker saves $100 a month from not having to pay commuting costs, it is same thing to their budget as if the cost of commuting fell by $100, although in the case of working from home, they also save the time spent commuting.

In short, the data indicate that most people are far better off financially today than they were before the pandemic. This doesn’t mean that tens of millions of people are not struggling. If a family was at the poverty line in 2019, they would still be struggling today even if their income was 10 percent higher.

However, what we can say is that the data does not give us any reason to believe that more people are struggling now than was the case before the pandemic hit. If we are hearing more stories of struggling families, it is because the media have chosen to give us more stories of struggling families, not because of an actual increase in the number of families who can’t make ends meet.

The Return of the Seventies: Is It a Wage Price Spiral?

The big fear of those of us old enough to remember the 1970s inflation is that we are on a path to a wage-price spiral. This is a story where higher inflation leads workers to demand (and receive) higher wages, which in turn get passed on in still higher prices. This would be a real problem, since it implies a story of ever higher inflation that is likely only broken by a recession, and possibly a very severe recession, like the ones we saw in 1980-82.

There are reasons for believing that this is not the situation we are now seeing. First, our labor market is very different today than in the 1970s, most obviously because it is far less unionized. In the 1970s, close to 30 percent of the private sector workforce belonged to a union.[2] Today the private sector unionization rate is just over 6.0 percent. For this reason, it is not clear that workers would have the bargaining power to sustain a wage-price spiral.

Many of us don’t consider the decline in unionization rates a good thing, but it is the reality. And, it has consequences. We cannot assume that the labor market of 2022 will respond to higher inflation in the same way as the labor market of the 1970s.

The second reason for believing that we are not seeing the beginnings of a 1970 wage-price spiral is that the current inflation is clearly not wage driven. In the 1970s, we were arguably seeing a real profit squeeze, with corporations having difficultly maintaining their profit margins.

That is not the problem we are seeing today. The capital share (profits plus interest) of net corporate income rose from 24.1 percent in the fourth quarter of 2019 to 26.7 percent in the third quarter of 2021, the most recent quarter for which we have data.[3]

This means that businesses can absorb higher labor costs, without passing them on in higher prices, by simply allowing their profit share to return to its pre-pandemic level. There are shortages of many items at present, which allow for price increases. If we think that these shortages will be overcome as supply chain conditions return to normal, then we should expect profit shares to return to something close to their pre-pandemic levels.

This would be true, unless we think that the pandemic has changed conditions of competition in the economy in some fundamental way that favors capital. This is of course a possibility, but it would be necessary to present an argument as to why it would be the case. Otherwise, we should assume that profit shares in a post-pandemic world won’t be very different than profit shares in a pre-pandemic world. This would allow for a substantial increase in wages that is not passed on in higher prices.

The Uptick in Productivity Growth

An important aspect to the 1970s wage-price spiral was a sharp slowdown in productivity growth. For more than a quarter century, from 1947 to 1973, productivity growth averaged almost 2.5 percent annually. From 1973 to 1980 it averaged less than 1.3 percent annually.[4] The rapid productivity growth in the earlier period allowed for annual increases in real wages of more than 2.0 percent.

This pace of wage growth could not be sustained in a context where productivity was only rising 1.3 percent annually. This meant that if workers sought to secure real wage gains that were close to what they had been seeing over the prior quarter century, it had to lead to either higher inflation or a profit squeeze, or both.

We are currently seeing the opposite situation. Productivity growth averaged less than 0.8 percent annually from the fourth quarter of 2010 to the fourth quarter of 2018. In the last three years, it averaged almost 2.3 percent. This allows for considerable room for real wage gains, without leading to higher inflation. The pace of productivity growth over the last four years means that real wages can be almost 7.0 percent higher now than in the fourth quarter of 2018, without leading to either a profit squeeze or an inflationary spiral.

Given economists’ track record in forecasting productivity growth (the 1973 slowdown was almost entirely unforeseen, as have been subsequent changes in trend growth), it would be foolish to predict the future pace of productivity growth, but there are reasons for believing that a more rapid pace of productivity growth could be sustained.

Specifically, the pandemic has forced many businesses to adopt more efficient ways of operating to deal with both fears of contagion and also the difficulty of finding workers. For example, many restaurants rely much more on on-line ordering, which requires less staff time to process orders. If pandemic-induced efficiencies become adopted more widely, it can mean further gains in productivity.

There also will be gains that affect living standards, that will not be picked up in productivity. At the top of this list would be the savings, noted earlier, in commuting expenses from the increase in the number of jobs where people can work from home. However, there have been other efficiencies, such as increased use of telemedicine or other ways in which people can substitute Internet exchanges for in-person contacts.

Whether or not the more rapid pace of productivity growth of the last three years can be sustained going forward, the jump in productivity over this period provides substantial room for wage gains that need not result in higher prices. This is the opposite of the situation we saw in the 1970s, when productivity growth was not fast enough to sustain the rate of wage growth workers to which workers had become accustomed. This difference doesn’t guarantee that we won’t see wage-price spiral, but it is a reason for believing it’s less likely.

Conclusion: Keep the Anti-Inflation Powder Dry

The Federal Reserve Board has indicated that it will soon begin to raise interest rates. It has already started to reverse course on its quantitative easing. These policies make sense in an economy that is both seeing rapid inflation and relatively low unemployment. At present, it does not need a strong boost from the Fed to reach something close to full employment.

However, there is little basis for the inflation-panic that some have been pushing. There are good reasons to believe that inflation is more likely heading lower than higher. This means the Fed should be cautious in its moves and wait to get a clearer picture of the problem it is facing.

Notes.

[1] It is important to note that the CPI index misses most of the source of the increase in drug costs since it tracks the prices of drugs already on the market. If a new treatment for heart disease or cancer comes on the market at a very high price, it is not picked up in the index.

[2] The private sector unionization rate is the most relevant variable for the wage-price spiral story. Public sector unions are more constrained in their ability to negotiate over wages, and in any case, their wage increases don’t get directly passed on into price increases.

[3] This calculation excludes indirect business taxes, so it refers to the capital share of the income divided between labor and capital.

[4] The link between productivity growth and wage growth is somewhat more complicated, but productivity growth for the nonfarm business sector is a useful first approximation.

This first appeared on Dean Baker’s Beat the Press blog.