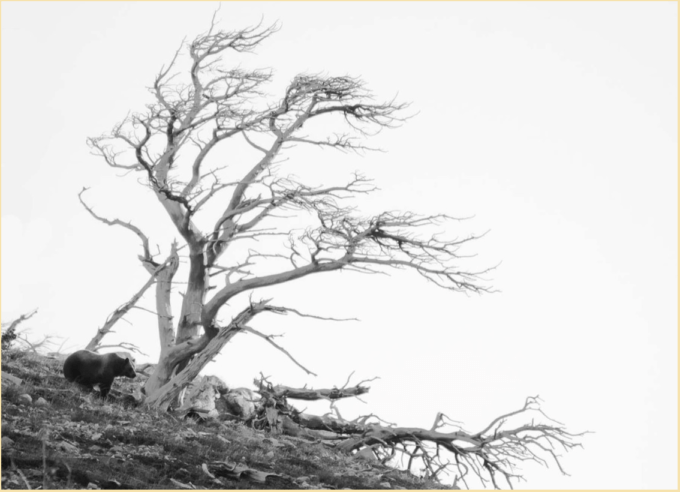

Photo by Steven Gnam.

I confess to a long love affair with the whitebark pine forests that define high peaks of the Northern Rockies. From their alpine summits, mountains recede to the horizon, hinting at the curvature of the earth. Here, whitebark pine feed and shelter species large and small, from 600-pound grizzlies to tiny voles.

My heart broke as healthy forests throughout the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem turned into an ocean of red dying trees in the blink of an eye, the result of a novel outbreak of native mountain pine beetles during the 2000s. Subsequent investigations have confirmed that whitebark pine has collapsed throughout North America due to the ravages of a nonnative fungal pathogen and an unprecedented outbreak of beetles unleashed by warming temperatures.

In response, the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) proposed during 2020 to protect whitebark pine as a threatened species under the Endangered Species Act (ESA). A final decision is expected this spring.

The FWS proposal brought back memories of the remarkable people that precipitated this moment and their largely unsung efforts to document the catastrophic demise of whitebark pine. Perhaps more importantly, this seemingly obscure campaign for a little-appreciated tree offers important lessons for conservation at a time of unprecedented threats.

Whitebark Pine Gets its Due

A federal safety net for whitebark pine could not come at a more critical time. Over 50% of the whitebark pine forests in the US have died – and threats are mounting, not just to the trees themselves, but the high mountain ecosystems that they sustain.

So far, efforts to address these threats have been piecemeal. Because the tree has little economic value, its plight has not been a priority for the Forest Service that manages the lion’s share of whitebark pine forests.

The FWS’ listing proposal was the long-delayed result of a 2008 petition that I helped draft as Senior Wildlife Advocate for Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC). Our concerns were reinforced by subsequent surveys of whitebark pine forests that I also helped lead. In 2011, the agency responded to our petition by concluding that whitebark pine deserved endangered species protections. But the agency dodged formally listing the species, claiming that the agency’s limited resources needed to be prioritized for protecting other more critically imperiled species.

A decade later, after updating their analysis and expanding upon our earlier work, the FWS agreed with our assessment that the tree was in urgent need of protection.

Creating Ecosystems: From Grizzlies to Trout

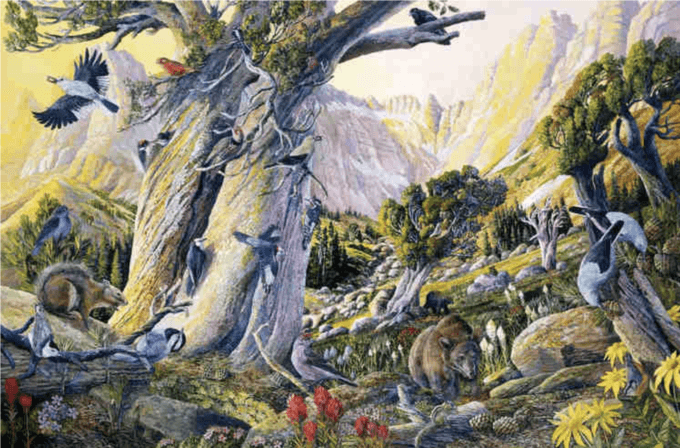

Scientists have long been fascinated with the whitebark pine trees that cling to wind-scoured outcrops at the highest elevations of any tree in the Northern Rockies, Sierra Nevada, Cascades, and much of interior Alberta and British Columbia. These trees endure bitter cold, icy winds, lightning strikes and poor soils – even as they create conditions within which other tree species and plants can flourish.

Whitebark pine functions as the lifeblood of the ecosystems where they grow. These trees play a surprisingly vital role in the hydrology of watersheds by shading the snowpack, slowing the melt of snow, reducing soil erosion and regulating stream flows. They sustain the region’s world-class trout fisheries, farms in the valleys below, and the human communities that depend on both. And their high fat-rich seeds feed a rich diversity of wildlife, including the Yellowstone grizzly bear. For more on the ecological role of whitebark pine, see this publication by David Mattson and others, and this overview by the Whitebark Pine Ecosystem Foundation.

Grizzly Threats

The threats to whitebark pine are numerous and complex but climate change looms largest of all. Some climate modelsproject that we could lose 70% or more of the environments cold enough to sustain whitebark pine by the end of this century.

Climate change is also driving increasingly frequent and large wildfires that are killing whitebark pine faster than they can reproduce while at the same time promoting competitors such as Douglas-fir. And warming temperatures have been triggering unprecedented outbreaks of native mountain pine beetles in whitebark pine forests. Tragically for whitebark pine, it did not evolve defenses capable of weathering the beetle’s attacks, unlike lower-elevation pines that co-evolved with bark beetles.

Whitebark pine is also threatened by white pine blister rust, a deadly non-native fungus that was introduced from Asia to North America around the turn of the 20th century. Starting from where it had been introduced along the Pacific coast, the fungus’ spores traveled far, wiping out some forests entirely.

Making matters worse, trees weakened by blister rust become more susceptible to beetle attacks. Meanwhile, in some parts of the Northern Rockies whitebark pine are being crowded out by other conifers following decades of misguided fire suppression.

A Rag Tag Army Unites Around Whitebark

A massive outbreak of pine beetles in Greater Yellowstone’s whitebark pine during the 2000s changed the course of whitebark pine conservation by galvanizing scientists, citizens, nongovernmental organizations, and agency officials, including members of the government’s Whitebark Pine Working Group. The crisis precipitated a loose-knit coalition to form focused on assessing the damage and sounding the alarm.

This coalition could not have been more different from the testosterone-fueled government committees at the center of managing politicized species such as grizzly bears and wolves that I was used to – committees that assiduously excluded the concerned public. Without money or political agendas at play, this group tended to attract people who were genuinely curious and cared about the organism they had gathered around.

At the time, government managers were focused on blister rust — collecting seeds from trees that show genetic resistance to the disease, and cultivating and planting them to propagate forests of less vulnerable trees. But the beetle outbreak demanded a new approach — one that took the form of a collaborative effort among NRDC, the Forest Service, and the Park Service to aerially assess the damage caused by mountain pine beetles in the Yellowstone ecosystem. Key partners included myself, entomologist and ecologist Jesse Logan, geographer Wally MacFarlane, ecologist Willie Kern, pilot Bruce Gordon of Ecoflight, Liz Davy of the Bridger Teton Forest, and NRDC’s Gaby Chavarria. Our results showed that less than 20% of mature whitebark pine forests in Greater Yellowstone were healthy or nearly so – and that only about 5% were completely untouched by beetles. A shocking 80% of mature whitebark had suffered medium to high levels of beetle mortality.

NRDC also helped convene gatherings of scientists and managers, and host events that brought journalists together with lead scientists to tramp through dead and living whitebark pine forests. Although whitebark pine was an obscure part of a remote ecosystem, we were able to leverage media interest by connecting its plight with high-profile issues, including grizzly bears.

At the same time, backcountry skiiers, outfitters and other “citizen scientists” began to band together to collect data on the health of whitebark pine forests. Equipped with cameras, strong legs, and a sense of adventure, people who were often not trained as scientists collected information about damage to whitebark pine caused by blister rust and beetles. We began to call ourselves “Whitebark Warriors.”

Some Whitebark Warriors: (L-R) Wally Macfarlane, Louisa Willcox, Jacques Regniere, Jesse Logan. Wind River Mountains, 2006.

I describe my role in this work as that of spinning plates, but reporters often called me NRDC’s whitebark pine “point person”. But I was not really in charge. My job was to try keep an eye on the plates in the air – media workshops, overflights, scientific presentations, coordination with agencies, and the rest

Our work culminated in the 2008 petition requesting that the FWS list whitebark pine as endangered throughout its range, a document that, at the time, represented the most comprehensive synthesis of the science on threats to whitebark pine.

Meanwhile, the beetle outbreak continued as a “sneaky, slow burn.”

Tracking a “Sneaky, Slow Burn”

Ever the Whitebark Warrior, Wally Macfarlane recently led a massive Forest Service effort to assess the health of whitebark pine since our 2009 survey. His team found that, although the out-of-control onslaught of beetles had waned, the outbreak continues to simmer — not manifest as in-your-face seas-of-red, but instead as a slow deadly burn adding up to more bad news. Even the highest and coldest whitebark forests have not been spared.

And with drought and warm temperatures, whitebark pine are stressed, making them more susceptible to beetles — and potentially vulnerable to another massive outbreak.

Whither Whitebark? And Why We Need a Precautionary and Democratic Approach

The fate of whitebark pine and its ecosystems hangs in the balance. Climate change is a particularly daunting threat, along with the complex and often surprising synergies among blister rust, climate change, wildfire and beetles that can be enormously hard to predict.

These synergies raise questions about the wisdom of relying on the two approaches that have dominated whitebark pine conservation so far: planting rust-resistant whitebark seedlings, and burning to free whitebark pine from tree competitors.

The ESA provides a roadmap for recovery with the listing of whitebark pine. The principle of precaution is built into the bones of the ESA — an admonition to carefully look at potentially unforeseen consequences before leaping into action and perhaps making a bad situation worse. So is the principle of “do no harm.” Both are vital given that we humans are notorious for mucking about with good intentions and causing more harm than good. Both principles are especially important in the case of whitebark pine given the enormous uncertainties.

Intrusive management manifest in controlled burning and other activities can miss the mark — and potentially make matters worse. For example, building roads can harm species dependent on remote country such as grizzlies. Given the Forest Services’ technocratic culture centered on exploitation, the FWS must be vigilant to prevent the agency from running amok.

At the same time, there are opportunities to ameliorate losses. Numerous experts believe we should be doing more to offset the reduced resilience in whitebark pine ecosystems by protecting more lands as Wilderness.

Clearly, no one person or agency has all the answers to the problems facing whitebark pine. Like all people who work for bureaucracies, employees of the FWS are prone to living in an echo-chamber that reinforces their preconceptions and worldviews — an approach that has had problematic consequences for grizzlies and other endangered species. The FWS would be wise to build on a history of successful collaborations by constituting a diverse whitebark pine recovery team with experts on blister rust, beetles, climate change, fire ecology, and forest management from inside and outside government agencies.

The Teaching Tree

Nothing that I’ve described here — including the request for a democratic recovery process — may seem surprising or even noteworthy. But the successes of this effort to protect whitebark pine are worth examining. The campaign for whitebark pine highlights some key ingredients for effective conservation unique in my long career of environmental advocacy.

My experience has taught me that successful conservation isn’t found in a cookbook – e.g., “sue the bastards” – but is, instead, a creative process arising from the involvement of particular people in a particular context. Even so, campaigns such as the one that arose around whitebark pine can offer lessons for those interested in upgrading the practice of conservation.

What follows is my attempt to tease out some of the lessons.

The Power of an Iconic Forest

With whitebark pine we were blessed by an iconic and beautiful tree in one of our most symbolically potent landscapes. Yellowstone and the West are cultural touchstones. For many, whitebark pine forests signify high-mountain country, pristine streams, and the freedom of wild places.

There is no doubt that the symbolically potent species and landscapes can inspire a broad cross section of people to advocate for positive change.

“Grandmother Tree,” an Ancient Whitebark in Crater Lake Park, Oregon.

Minimal Power and Wealth Stakes

Because whitebark pine grow in remote country and do not make good lumber, loggers have not engaged in the debate over these forests – at least not yet. So far, this has meant less contention than is commonly the case in conservation.

As a result, the ideological stakes have also been low, in stark contrast to the bruising battles over grizzlies and wolves where ideological stridency is extreme, people invested in making money by exploiting nature are powerful, and opportunities for collaboration are rare.

The lesson here is simple: low power, wealth and ideological stakes tend to create more opportunities. Admittedly, keeping the stakes low is often out of one’s control.

Of Shared Passion and Funding Shortages

With whitebark pine, we were blessed by passion and curiosity shared among leaders in government, academia, nongovernmental organizations, and volunteer groups. This contributed to a more inclusive and collaborative atmosphere and a better orientation to problems than is typical of most conservation campaigns.

Importantly, government leaders were generally friendly, open and respectful – and eager to solve problems. Not accidentally, they were also largely female. Their approach stands in stark contrast to the arrogant, “us versus them,” counterproductive orientation typified by the largely male silverbacks involved in managing grizzly bears.

In addition, funding shortages in the government and academia made collaboration with non-governmental groups imperative. Because no one agency or entity had the resources to adequately address the crisis, we had strong incentives to work together.

A Force for Change Outside Government

Outside the government, the whitebark warriors came together as a powerful force for change. Without it, the government almost certainly would not have given the tree the protections it deserved.

We were fortunate that the right people showed up at the right time with the right skills, that people got along, and that no one person or organization was invested in being in control and appropriating credit for everything that happened. Decentralized decision-making meant that the work did not flounder on the shoals of organizational jealousies and bureaucracy – scenarios I have seen often.

Of Pointy Sticks

This collegial atmosphere begs the question of why we had to file a listing petition. The reasons are straightforward. First, bureaucratic inertia in government is legendary. Second, whitebark pine was not a high-profile species with a vocal constituency. Compounding this, agency leaders tend to be motivated by climbing the career ladder — not addressing substantive problems or responding to pressure from underlings.

Our listing petition helped cut through the bureaucracy. Even so, the FWS drug its heels and for nearly three years failed to produce a response to our petition, despite a mandate to do so in only one – and only because NRDC threatened to sue. Its 2011 finding that listing of whitebark was warranted meant that the agency had to continue investigating threats – investigations that finally convinced the agency to list the species.

As a bottom line, it helps to have a pointy stick even if the bureaucrats in charge are basically supportive.

Power of the Press

Journalists proved to be powerful allies by helping to educate the public about the ecological role of whitebark pine and threats to its existence. As important, journalists elevated the problem inside the federal government.

At the time of our work, we were able to leverage reporter interest in climate change and the government’s proposal to remove Yellowstone grizzly bear protections. And the sight of entire mountain ranges of red, dying forests in and around our oldest park was hard to ignore.

But positive press about any environmental issue does not fall into your lap. There was no substitute for bringing reporters into these iconic forests in the company of articulate and informed experts.

Of Alchemy and the Path Ahead

In decades of conservation work, I have rarely seen such collective boldness and so little of the kind of lethargy, internecine conflict and goal inversion that plagues otherwise laudable environmental campaigns. I felt like I was part of an alchemical reaction, rare and spectacular as the northern lights.

The imminent listing of whitebark pine under the ESA opens a new chapter. It remains to be seen whether the can-do spirit I’ve described here will weather the kind of bureaucratic and political traps that often hamper endangered species recovery, including entrenched views, narrow vision, and turfiness over power and resources. Although more money is clearly needed at this juncture, money can also attract those with ignoble motives.

Whitebark pine is in terrible trouble. At this critical juncture, diverse perspectives and a democratic process tempered with caution and humility promise to advance conservation more effectively than the efforts of one agency operating in a silo. Given the challenges afoot, working to recover these magnificent forests should bring out the best in us and the government that operates at our behest.

What is at stake is nothing less than the wild heart of our high mountain country of the West — and an extended ecological family that includes ourselves.