Moon rise over Emigrant Peak and Yellowstone River, Paradise Valley, Montana. Emigrant Peak and Yellowstone River in Paradise Valley. The East Paradise Grazing Decision will increase grazing by livestock on Emigrant Peak and adjacent areas of the Six Mile Creek drainage, an important area for wildlife. Photo George Wuerthner

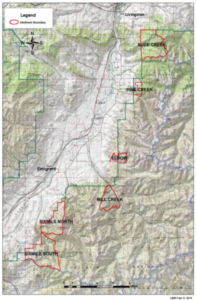

The Custer Gallatin National Forest (CGNF) recently released its decision on the future of six East Paradise Grazing allotments. The allotments, Suce Creek, Pine Creek, Elbow Creek, Mill Creek, Six Mile South, Six Mile North lie south of Livingston, Montana, and near or adjacent to the Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness.

Grazing allotments are outlined in red. The lowest two Six Mile allotments are near Chico Hot Springs and Emigrant Peak.

Although the Forest Service considered a no-grazing alternative, it chose Alternative 3, which EXPANDS total acres open to livestock grazing over the present situation, requires costly “range improvements” like pipelines, fencing, and other taxpayer-funded development to mitigate livestock impacts—all to permit the continued use of public lands for the private profit of local ranchers.

These allotments just north of Yellowstone National Park play an essential role in sustaining the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem. Continued livestock grazing on these allotments will potentially impact the region’s wildlife, vegetation, soil, and water.

The decision is a violation of Public Trust. As wildlife biologist Jim Bailey has written: “Public-trust resources are a result of, and the basis for, democracy. The gradual erosion of public control of trust resources, with a decline in the qualities and availabilities of these resources for all the people, diminishes the value and expression of democracy.”

This violation of Public Trust is exactly what the CGNF has done by maintaining livestock grazing on some of the most valuable wildlife habitat in the entire Upper Yellowstone valley.

Cattle naturally gravitate towards wetlands and stream riparian areas, trampling stream banks, polluting water, and compacting soils. Photo George Wuerthner.

Indeed, the Forest Service’s own analysis concluded: “For most resource areas, the removal of livestock grazing would provide the most benefit. Livestock would not be present to impede recovery of riparian/stream conditions or compete with other species for forage and space. Removal of livestock would also eliminate any threats to wildlife resulting from depredation or human encounters.”

In particular, the Six Mile North (Emigrant Peak) and Six Mile South allotments are located south of Chico Hot Springs. Both are adjacent to the Dome Mountain Wildlife Management Area, a major wintering range for elk. In addition, Elk calving occurs in the spring in this area, and both grizzly bears and wolves regularly patrol the area.

The elk use of this area is so heavy it is nearly impossible to take even a step here without stepping on elk droppings.

To make matters worse, the Forest Service may open grazing on June lst when elk are still calving, introducing another impact to the wildlife since elk tend to socially avoid and thus are displaced from areas with active cattle grazing.

Elk grazing on private lands just below Dome Mountain. The CGNF admits in its EIS that closing the Six Mile allotments to livestock grazing would encourage elk to remain on public lands, avoiding conflicts with private landowners, however, they choose to expand grazing in that area. . Photo George Wuerthner.

The final EIS even admits this conflict. “The no grazing alternative would maintain or enhance forage capacity for elk within the analysis area and reduce competition for space. The no grazing alternative may also encourage elk to remain on National Forest lands and alleviate distribution problems that can occur with elk seeking available forage on adjacent private lands.”

However, as expected, the CGNF decided to maintain grazing on three allotments by using “adaptive management,” a euphemism for spending a lot more taxpayer money on things like fencing, pipelines, and water troughs. It also relies on monitoring (that seldom happens) and suggests that grazing can be expanded if there is an upward trend.

The solution for livestock damage is to invest more public funds into “range developments,” typical of range managers’ response to livestock damage—spend more taxpayer money to allow the continued use of public lands when any rational person would close the allotment.

Plus, all the above remedies have externalities that are not mentioned in the document. For instance, constructing fences can hinder the movement of wildlife. Often fences are not maintained. Livestock can quickly get into fenced areas. Piping water from springs to water troughs may reduce trampling near the spring but reduce the overall water flow at these sources, harming birds, amphibians, and other wildlife.

All of this is a twisted logic to continue the private use of public lands for private profit and likely to justify the job of the range con.

Grizzly bears utilize riparian vegetation in the spring and seek out elk calves. By opening up allotments to grazing as early as June 1st, the CGNF increases the odds that cattle will come into conflict with grizzlies. Photo George Wuerthner.

Putting cattle on these allotments will harm predators by setting up potential conflicts. For instance, grizzly bears graze extensively on vegetation in the spring. Changing the turnout date to June will result in direct competition between cattle and bears, but more importantly, it increases the likelihood that bears will feed on cattle. Even if bears do not feed directly on live cattle, they often feast on dead animals. Therefore, if the carrion is a dead cow, it can predispose them to feed on cattle in the future. This can result in the removal (killing) of bears.

The social displacement of native ungulates like elk by livestock can either reduce available prey for the bears or force bears into less secure areas as they seek to find prey. For example, bears seek out carrion and elk calves at lower elevations in the spring. These are often the same places where livestock are first permitted to forage on public lands, creating a potential livestock depredation situation by bears.

The CGNF trivializes these conflicts. “Regardless, it is possible that grazing at the current levels in these allotments could indirectly contribute to surprise encounters with forest users or livestock producers and contribute to livestock losses (through depredation) that could lead to bear injuries or mortalities through management removals in and near the project area. Removal and relocation of grizzly bears, if it were to occur, would likely result in the short-term reduction of grizzly bear abundance in the project area itself. To some extent, its vicinity, at least until new bears are recruited into the area through emigration.”

Another potential conflict lies with bison-cattle. Bison are attempting to migrate out of Yellowstone NP to other public lands. The area around Dome Mountain, the Six Mile drainage, and adjacent Dome Mountain Wildlife Management Area could eventually support wild bison (assuming the current policy of killing bison leaving the park is terminated). Instead, bison are being killed because of the irrational fear of brucellosis transmission from bison to cattle (which has never been documented for bison).

The East Paradise EIS admits the conflict is almost non-existent. “With transmission of Brucella lower in the months of June 1 and essentially nonexistent by June 15th, the risk to livestock from bison/livestock interaction is greatly reduced.” Nevertheless, one can expect that cattle on the Six Mile allotments will increase the justification for bison slaughter to preclude bison utilization of the area.

The obvious livestock bias of the Forest Service Range Con is demonstrated in a discussion of range tren in Table 9. The portions of the allotments with a “downward trend” are due to conifer “encroachment.” This is only a problem for livestock production because it “diminishes the production of forage” for cows.

There is a lot of smoke and mirrors in the decision. Even though the CGNF has decided to keep cattle off the Suce Creek, Mill Creek, and South Six Mile allotments, this decision may be temporary.

For instance, the Suce Creek Allotment is “closed” to grazing, but considered a “forage reserve” that can be utilized if drought, fire, or other natural events limits forage on other allotments. Mill Creek is only closed to grazing due to high levels of non-native vegetation. Once a greater percentage of native vegetation is restored, it too could be opened to grazing.

Pine Creek Falls is a popular hike from the Pine Creek Campground. The campground will be open to occasional livestock grazing. Photo George Wuerthner.

The Pine Creek allotment includes the Pine Creek campground. Unfortunately, the campground will be available for cattle grazing every five years—doesn’t that sound like a good place to camp.

In what could be termed a sleight of hand, the CGNF will continue to keep the South Six Mile allotment closed to grazing, but they will transfer 7,086 acres to the North Sixmile All by absorbing three of the four existing pastures in the South Sixmile allotment. So more acreage will be available for livestock grazing, even though the South Sixmile Allotment remains “closed” to grazing.

Because of the area’s steep topography, most grazing is concentrated in the valley bottoms and near water sources like streams. So the majority of livestock use is in the very areas most attractive to wildlife. Cattle, in particular, are drawn to riparian areas where there is water, shade, and abundant forage. But these same areas are critical for wildlife from amphibians to grizzly bears.

Even if all the ecological damage were not justification enough to permanently close these allotments, the Forest Service failed to do a complete economic analysis of trade-offs. It merely asserts that ranching is “important” to Park County.

Rancher herding cows on private land in Paradise Valley. All agriculture contributes to less than 1.8% of income in Park County, while tourism, primarily related to wildlife and wildlands of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, is responsible for 31.5% of all income. Photo George Wuerthner.

However, according to Headwaters Economics, only 1.8% of the income in the county is derived from Ag. By contrast, 31.5% of the county’s income is the result of travel and tourism—much of it is based on wildlife viewing of bison, elk, wolves, bears, and fishing in the Yellowstone River. These values are compromised by the livestock damage to public lands and wildlife.

Furthermore, Agriculture in Park County consists of more than livestock production. There is wheat, and small garden crops, and other agricultural endeavors. Thus, the contribution of cattle ranching is something less than 1.8%, and the percentage of income derived from public lands grazing is an even smaller subset of this minuscule amount.

Current federal grazing fees are $1.35 an AUM. The FS proposes approximately 474 Animal Unit Months or the forage consumed by a cow and a calf in a single month. Though this can be adjusted given the weather and other consideration, the public would receive only $640.00 in grazing fees per month in a typical year. Given that even if the grazing season were extended to begin June lst and to end Oct 15, the overall maximum grazing fee paid by permittees for utilization of authorized allotments would be about $2880.00 annually.

Just the cost of monitoring and “range improvements” (like pipelines and fencing) will cost far more than what the public receives in grazing fees.

Add in the environmental costs like water pollution, damage to riparian areas, forage competition between native herbivores like elk and cattle, the spread of weeds, and impact on recreation (camping and hiking among cow pies is less than inviting), it is evident that the CGNF is not working for the public interest, but rather as a handmaiden to the local ranchers.

Although the CGNF did not include any areas in the existing Absaroka Beartooth Wilderness in the expanded grazing, some of the adjacent roadless lands like the Dome Mountain and Emigrant Peak areas are roadless and proposed for wilderness designation by the Gallatin Yellowstone Wilderness Alliance.

The CGNF justifies the continuation and expansion of livestock grazing (one allotment will be expanded) based on the agency’s Multiple Use Principle. While livestock grazing is permitted on Forest Service, it is not required. Despite the fact that the CGNF got over 23,000 comments, the majority of them supporting Alt. ! which would have terminated all livestock grazing on these six allotments, the CGNF chose to favor private grazing operations over the public interest.

For a more complete analysis of this proposal see this link.

The East Paradise allotments have higher public value for wildlife, ecosystem function, and wilderness recreation—all of which are compromised by the presence of domestic livestock.