Subsidized logging in the name of fuel reductions on the Deschutes National Forest in Oregon. Logging accounts for 35% of Greenhouse Gas Emissions in Oregon. Photo George Wuerthner.

Congress just passed the big infrastructure bill, and I expect President Biden will sign it—maybe before you read this commentary.

Funding is for numerous projects including upgrading bridges, highway construction, expanding broadband in rural communities to environmental restoration like reclaiming abandoned mines.

As with any broad legislation, there is probably a lot of “pork” as well as likely improvements that ultimately are necessary to the country’s infrastructure. I will leave the judgment of these things to others.

However, the bill does deal with wildfire issues. Some of which are positive, such as providing funds to bury powerlines (which are common ignition sources for wildfires) to funding to reduce the flammability of homes.

Nevertheless, the main thrust of the legislation continues to promote the idea that “fuels” are the problem and logging is the primary way to deal with climate-induced wildfire.

Among other provisions, the Infrastructure Bill includes a legislative mandate for 30 million acres of additional logging on federal public lands over the next 15 years. Thirty million acres are nearly equal to the area of Maine, New Hampshire, and Vermont combined!

The legislation provides $3.3 billion for wildfire risk reduction efforts, including hazardous fuels reduction (a euphemism for logging), controlled burns, community wildfire defense grants, collaborative landscape forest restoration projects (another name for logging), and firefighting resources.

The emphasis on “fuel reductions” has several immediate problems.

Ironically, logging will only exacerbate CO2 emissions driving climate warming and make it far more challenging to meet the Biden administration’s 50% reduction in climate warming. As noted in a recent letter to Congress signed by more than 200 scientistslogging in U.S. forests emits 723 million tons of uncounted CO2 into our atmosphere each year—more than ten times the amount emitted by wildfires and tree mortality from insects combined.

Although the burning of fossil fuels for transportation accounts for the greatest percentage of US Greenhouse Gas Emissions, the emissions from logging in U.S. forests are now comparable to the annual CO2 emissions from U.S. coal-burning and annual emissions from the building sector. For example, logging accounts for 35% of Oregon’s annual CO2 emissions, more than all the state’s cars, trucks, and airplanes!

Besides the fact that logging contributes to climate warming, we have studies and numerous examples across the West where fuel reduction does not work in the face of extreme fire weather.

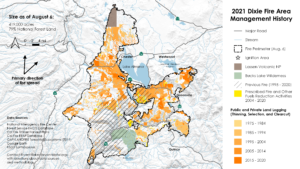

For instance, two of the largest fires this past summer, the 900,000 acres plus Dixie Fire in California and the 400,000 acres plus Bootleg Fire in southern Oregon, occurred where most of the land had been previously logged/thinned. A rough estimate suggests that 75% of the Bootleg Fire area had experienced fuel reduction, including logging/thinning and prescribed burning.

This map of the Dixie Fire perimeter in August shows how ineffective logging/fuel reductions were in controlling the blaze. All the brightly colored portions of the map were previously logged and thinned. The blue is Lake Almanor near Chester, California. Map by Bryant Baker.

I visited both burns and found where even large clearcuts with almost no fuel failed to halt the spread of these wind-driven blazes.

Yet despite these failures, the Forest Service, timber industry, and its allies like the Nature Conservancy, Conservation Northwest, California Wilderness Coalition, Greater Yellowstone Coalition, and other so-called “conservation organizations” continue to support fuel reductions, despite their apparent inability to preclude large blazes.

Worse for our communities is that logging/thinning by opening the canopy logging can hasten the drying of fuels and increase wind penetration—both major factors in fire spread. The irony seen in numerous fires across the West is that wildfire severity and spread are typically proportionally lower in areas where logging/thinning is prohibited, like wilderness areas and national parks where presumably fuel biomass is higher.

Wildfires burn through previously “thinned and logged” areas, especially when high winds push fires through and over such projects. For example, the 48,000 acre Eagle Creek Fire of 2017 that burned some of the forestlands within the Columbia River Gorge jumped the mile and half wide Columbia River (with no fuel) to ignite blazes on the Washington side of the river.

The legislation undermines environmental protection by weakening current laws to create a broad exemption for logging projects on federal lands.

The infrastructure bill language will permit the continued use of “Categorical Exclusions,” which eliminates environmental analysis under NEPA for an unlimited number of logging projects on federal lands. According to the legislation CEs projects up to 1,000 feet wide and 3,000 acres in size are permitted. CEs were initially designed to allow the Forest Service to do small tasks like constructing an outhouse in a campground without bothering with an Environmental Impact Statement or other burdensome paperwork. Instead, CEs provisions are regularly exploited to facilitate logging.

For comparison, a football field is approximately 1 acre in size. Therefore, every CE can impact an area the size of 3000 football fields.

The emphasis on fuel reductions is misguided. Logging is not benign. It significantly contributes to GHG emissions, the spread of weeds, displaces wildlife, causes sedimentation that compromises aquatic ecosystems, and much more. Moreover, since one can’t predict where a fire might occur, most of these “fuel reductions” never encounter a fire during a time when they might be effective. So we suffer these negatives now and gain few if any benefits in wildfire reduction and increase climate warming that is ultimately the source of growing wildfire size and spread.