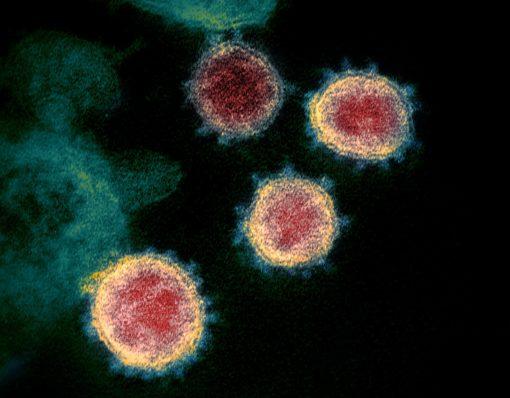

Photograph Source: NIAID – CC BY 2.0

When U.S. President Donald Trump cut off his government’s funding to the World Health Organization (WHO), one of his grievances was that the WHO—under Chinese tutelage—failed to declare the global coronavirus outbreak as a pandemic soon enough. Not long after the virus brought patients to Hubei Provincial Hospital, the Chinese medical and public health authorities brought it to the notice of the WHO. The WHO investigated the virus over the course of early January, sending a team into Wuhan and making public whatever credible information it could report.

The WHO’s International Health Regulations (2005) Emergency Committee met twice in January, first on January 22-23 and then again on January 30; in the first meeting, the committee felt it had insufficient evidence to declare an emergency, but at the second meeting it took the decision to declare a public health emergency of international concern (PHEIC). This is the penultimate step for the WHO; on March 11, after it became clear that the virus was spreading across borders, but not before the WHO made many warnings to governments, the WHO declared a global pandemic.

Trump and his Democratic rival Joe Biden, as well as a host of other U.S. politicians, made the argument that the WHO did not act fast enough with its declaration. Whatever problems posed to the United States by the virus were not the responsibility of the U.S. government, they suggested; the fault lay with the Chinese government and with the WHO.

Our investigation finds that this argument has little foundation. The WHO’s reporting mechanisms are sound, but the WHO’s own ability to make these formal declarations—a public health emergency and a global pandemic, which come with serious financial consequences for member states—has been circumscribed; those who have constrained the World Health Organization—the United States and European nations—are the very same countries whose leaders are now complaining about Chinese influence over the WHO.

Revisions

By the 1990s, it had become clear that the WHO’s old International Health Regulations—originally issued in 1969, with only a few minor updates and new editions over the two decades after that—were inadequate. For one, these regulations were produced before the emergence of very infectious, lethal, and recurrent infections such as Ebola and the avian influenzas. Secondly, these old regulations were made before air travel began to move about 4.3 billion passengers per year, the scale of air traffic now making the movement of viruses so much easier.

In May 2005, the 58th World Health Assembly revised the 1969 regulations, pointing out that the new regulations would “prevent, protect against, control and provide a public health response to the international spread of disease in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risks, and which avoid unnecessary interference with international traffic and trade.”

The North American and European states, in particular, insisted that the declaration of a PHEIC or global pandemic only be made after it was clear that air travel and trade would not be unduly interrupted. This restriction, essentially the core foundations of globalization, has constrained the WHO since 2005.

The 2009 Test

The new WHO regulations were tested when a new influenza emerged out of Mexico and the United States in mid-April 2009. This H1N1 was a combination of influenza virus genes that had links to swine-lineage H1N1 from both North America and Eurasia (thus the 2009 outbreak was commonly known as “swine flu”). It was first detected on April 15. On April 24, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention uploaded a gene sequence onto a publicly accessible influenzas database. On April 25, ten days after the first detection of the virus, the WHO declared the 2009 H1N1 outbreak a PHEIC. On June 11, the WHO said that a global pandemic was underway.

In 2020, the WHO took a month to declare a PHEIC for the coronavirus and took an additional two months after that to pronounce a global pandemic. It was slower to announce the emergency, but it took the same time to declare a global pandemic.

By July 2009, the dangerous H1N1 virus had a less lethal impact than the WHO had feared. However, for the full year from its first detection, 60.8 million people were infected and 12,469 died.

Almost immediately, the WHO was attacked for the June 11 description of the outbreak as a pandemic. When the WHO declares a pandemic, governments are expected to do a variety of things including mass purchase of drugs and vaccines. These are costly.

That December, members of parliament in the Council of Europe opened an inquiry into the WHO declaration. Fourteen members of the Council charged the WHO with what was essentially fraud. They said that “pharmaceutical companies have influenced scientists and official agencies, responsible for public health standards, to alarm governments worldwide. They have made them squander tight health care resources for inefficient vaccine strategies and needlessly exposed millions of healthy people to the rise of unknown side-effects of insufficiently tested vaccines.” “The definition of an alarming pandemic,” they wrote, “must not be under the influence of drug-sellers.”

The criticism of the WHO stung. It had declared a pandemic, but the virus had stabilized very soon after the declaration. The WHO responded to such criticism with humility. “Adjusting public perceptions to suit a far less lethal virus has been problematic,” the WHO responded. “Given the discrepancy between what was expected and what has happened, a search for ulterior motives on the part of the WHO and its scientific advisers is understandable, though without justification.”

Trump’s Attacks

A WHO official told one of us that the agency had been shaken by the assault in 2009. Over the past ten years, the agency has struggled to regain its confidence, working through the Ebola outbreak in 2014 and then Zika in 2016. In neither of those cases was there a need to make any global declaration.

This year, the WHO declared a global pandemic within three months of the first cases. But there is no doubt that the attack on the WHO a decade ago has made an impact. Former WHO employees tell us that fear of being attacked like this by the main donors seriously hampers the independence of the WHO and its scientific advisers. Trump’s current attack is going to weaken further the ability of the WHO to operate at its own pace and with credibility.

The World Health Organization is not the first UN agency to face the wrath of the U.S. administration. The Trump administration sent its budget to Congress with zero dollars for a line item called International Organizations and Programs. Under this line item comes United States funds for UN Development Program, UNICEF, UNESCO, Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, UN Women, and UN Population Fund. In 2018, the United States stopped funding the UN’s Palestine agency (UNRWA). When the UN is useful, the United States uses it; when the UN goes against United States interests, it will lose its funding.

When Trump said that the WHO is “China centric,” he offered no evidence; he did not have to.

No doubt that the United States is currently facing the wrath of the global pandemic. If the U.S. government had begun to plan effectively after the WHO declared a public emergency on January 30 or even when it declared a global pandemic on March 11, the problems would not be so grave. But there was no planning at all, which is distressing. As George Packer put it in the Atlantic, the United States in the months after January was “like a country with shoddy infrastructure and a dysfunctional government whose leaders were too corrupt or stupid to head off mass suffering.” From Trump, the U.S. citizenry got “willful blindness, scapegoating, boasts, and lies.” This sums it up. Part of the scapegoating was directed at China; it is far easier to blame China—already part of a dangerous trade war and a simmering regional struggle in Asia—than to accept responsibility oneself.

This article was produced by Globetrotter, a project of the Independent Media Institute.