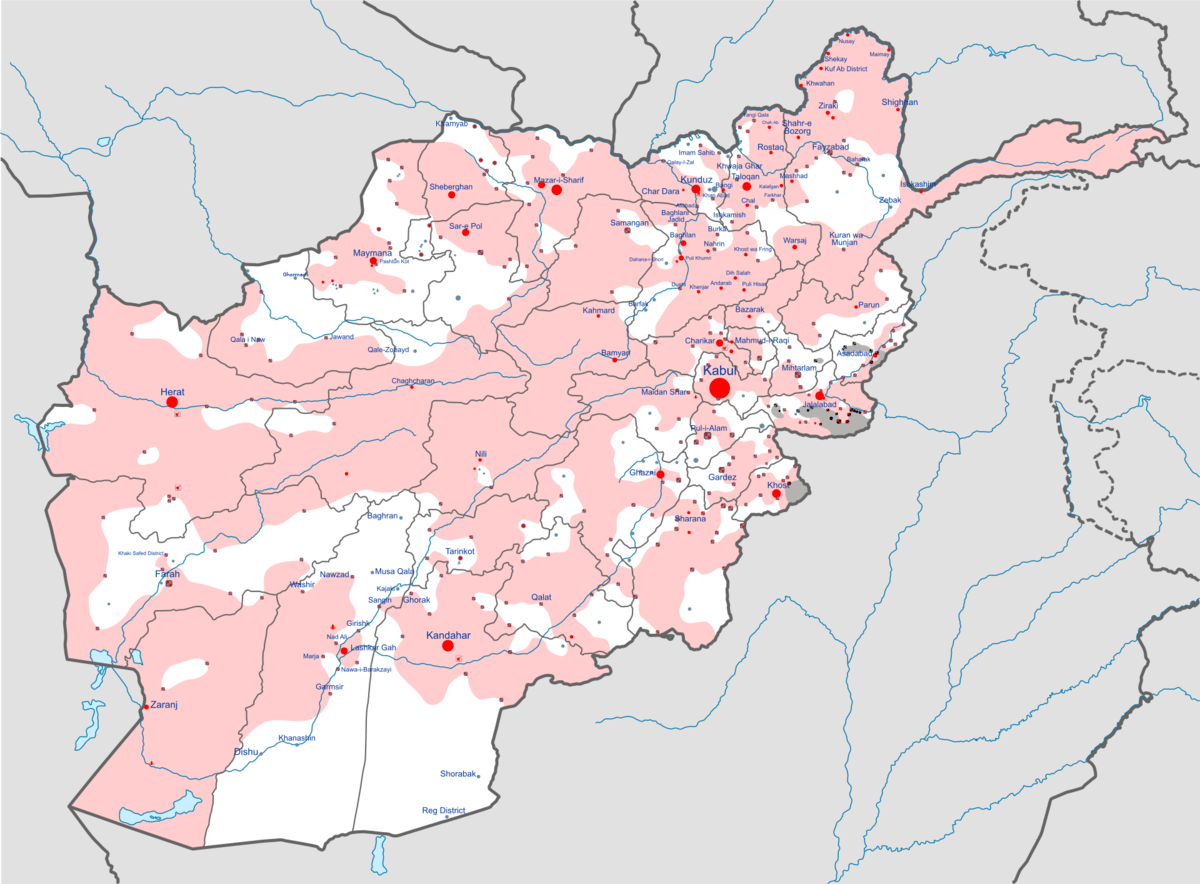

Map of the War in Afghanistan (2015–19) – Source: Ali Zifan – CC BY 2.0

On March 3, US president Donald Trump spoke (via telephone) with Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, chief of the Taliban’s Doha diplomatic office and signer, on behalf of his organization, of the recently concluded Afghanistan “peace deal.”

“The direct contact between an American president and a top Taliban leader would once have been unthinkable,” writes Michael Crowley at the New York Times.

Why? Crowley doesn’t elaborate, but in my opinion the claim of unthinkability goes a long way toward explaining why the US government spent nearly two decades unsuccessfully attempting to wrest control of Afghanistan from the Taliban before coming to its senses — in the person of Donald Trump — and seeking to bring the folly begun by George W. Bush and continued by Barack Obama to an end.

It was, in a word, “unthinkable,” for the longest time, that a bunch of Central Asian hillbillies might successfully resist the will of Washington for five times as long as Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia did.

It was “unthinkable” that US forces better armed, better trained, and more lavishly funded than those who landed at Normandy or took Okinawa could possibly be brought low by light infantry with no air force, no artillery, and no safe logistical haven, wielding weapons scavenged from a war which ended 30 years ago.

But that’s what happened.

When a war ends, it’s reasonable to expect that the losing regime’s head of state will talk to and treat with whomever the winning team designates as its representative, if that’s what the winning team demands.

The word isn’t being openly used by either side, but let’s call it what it is: Surrender.

The US government has surrendered in Afghanistan.

No, not unconditionally. But it has surrendered nonetheless.

And that’s a good thing.

The war became obviously doomed to go down as a fiasco within weeks of the US invasion, when the Bush administration stopped pretending the US presence was about liquidating al Qaeda and started in with a bunch of “nation-building” nonsense.

Eighteen years — not to mention several thousand American and more than 100,000 Afghan deaths — later, the Taliban controls more of the country than it did those few weeks after the invasion.

The US was never going to win the war.

The only question was how long the US would spend losing the war before admitting it had lost the war.

That question has now been answered: Eighteen years, four months, and 25 days.

If part of the price of extricating the US armed forces from the Afghan quagmire is a phone call between the losing side’s president and the winning side’s chosen representative, that’s not just “thinkable,” it’s a price we should all applaud Trump for paying.