Photo Source Noël Zia Lee | CC BY 2.0

Ecologists have long “speculated” that ungulates—hooved animals including deer, sheep, and bison—learn from their families and peers. That they learn strikes me, an avid walker-through-the-woods, as obvious.

Why wouldn’t they trust others in their communities, and adopt the elders’ patterns of movement?

But science requires verification. And in a recent study of rams and moose, a team of academic and government researchers recently confirmed that ungulates learn and teach through their generations.

They learn the spots were new shoots spring up, and when. They time their travel accordingly. Their memories’ maps, collectively drawn, guide the migration of hooved animals. Each generation confirms what earlier generations knew, then expands upon it. This is how ungulates maximize the nourishment available from accessible territory. This is how they find the optimal fat and protein sources to fortify them for the harshest winters.

Without intergenerational knowledge, ungulates lack migration know-how. Thus, relocating or redirecting animal groups by way of green corridors is a limited solution to human sprawl. To respect biological communities is to leave what they know intact.

Dearth of Memories at Valley Forge

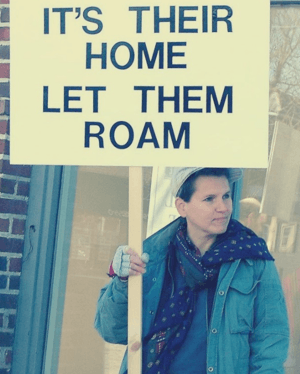

White-tailed deer are indigenous to the eastern United States. Photo of the author courtesy of Philadelphia Advocates for the Deer.

Deer are ungulates, so I assume they will be officially deemed learners as this line of research continues. I live near Valley Forge, Pennsylvania, where deer are shot in official cull projects—now typical throughout the mid-Atlantic region.

No one needs a scientific survey to notice that very few deer at Valley Forge National Historical Park have aged beyond two years.

National Park Service employees attributed woodland damage to deer. Their Environmental Impact Statement also brought up gripes unrelated to biodiversity: “The presence of deer on neighboring properties has been linked to loss and damage of ornamental vegetation.”

Collaborating with the then-director of the University of Denver environmental law clinic, I developed the strategy to halt the kill through Friends of Animals v. Caldwell, which reached the Third Circuit Court of Appeals in 2011. By 2010, the Third Circuit had decided against letting nature take its own best course on this five-square-mile piece of land in Pennsylvania’s Chester and Montgomery Counties.

According to park officials there were 1,277 deer when they first baited the hapless beings and shot all they could, looking to reduce this long-established group to fewer than 185.

Any individual deer who survives one such annual massacre is highly unlikely to make it through the next. The lifespan of a deer is about 16; Valley Forge’s deer are infants and adolescents. For them, preserving intergenerational memory is out of the question.

The Shortcomings of Species-Saving Law

Why don’t we value what happens to the animals we deem ordinary or prolific? We value species preservation, but we do not wish to accord the animals themselves respect all along—respect that could prevent the dramatic circumstances of those now hanging by a thread.

And just because we live in the outskirts of a city—an eastern one, at that—doesn’t mean the evolution happening around us warrants no respect. Indeed, given how much of the land we’ve built on, evolution now depends heavily on suburban bio-communities.

Moreover, to respect ordinary ungulates is to respect predator populations.

The Environmental Impact Statement for Valley Forge says bobcats “potentially could be supported by habitats within the park” and acknowledges the actual presence of coyotes. But it downplays these animals’ abilities, stating that “these predators have been shown not to exert effective control on white-tailed deer populations.” Based on this cursory dismissal, the Third Circuit rejected the legal challenge to the shooting plan, stating: “The NPS adequately considered and appropriately rejected the option of coyote predation because there was not a shred of evidence that such an option could achieve the NPS’s stated goals.”

In fact, a substantial body of evidence indicates that a balanced ecosystem includes key predators, and that predators control deer. Science in South Carolina and elsewhere shows coyotes as highly capable deer predators. It has for years.

Pharma Versus Freedom

Some animal advocates want an ostensibly easy out. They insist we should control deer “humanely” by foisting birth control on these animals. Why they’re not offended by such obvious manipulation continues to baffle me.

The Valley Forge managers decided to insert deer contraception into the management plan as a possible supplemental control measure. This was largely in response to Priscilla Cohn, a retired philosophy professor living in Montgomery County, who showed up at the public meetings and advocated for the use of an experimental deer contraceptive known as porcine zona pellucida.

“It has been offered that immunocontraceptive vaccines offer significant promise for future wildlife management,” the Valley Forge managers wrote. Their management plan vowed to integrate pharmaceutical control “when an acceptable chemical reproductive agent becomes available.”

The National Park Service is willing to go to any length to produce artificial, people-pleasing animal populations, rather than to teach respect for natural predator-prey relationships to our own future generations.

It’s November.

Detour signs at Gulph Road, and nighttime plastic barriers around the parking areas, appear every November—ever since the shooting started eight years ago. They’re up now.

The initial four-year killing plan could, by its own terms, continue if officials saw fit to extend it. They did.

The deer living in the park now, of course, are different. These ones are young. Leaderless. They seem to me like adolescents, hanging out at the fringes of the danger zone that, a decade ago, was their suburban oasis. What the National Park Service did to them cannot be described in numbers and statistics.

Meanwhile, Pennsylvania authorizes hunters and trappers to kill tens of thousands of coyotes annually. More than a thousand bobcats—also deer predators—will likely succumb again to the winter’s hunting and trapping season.

The National Park Service would do well to work with the state to end these practices, and give white-tailed deer the opportunity to experience adulthood. The Service ought to have started a decade ago. Given the new science on migration and memory in ungulates, it should at least start now.