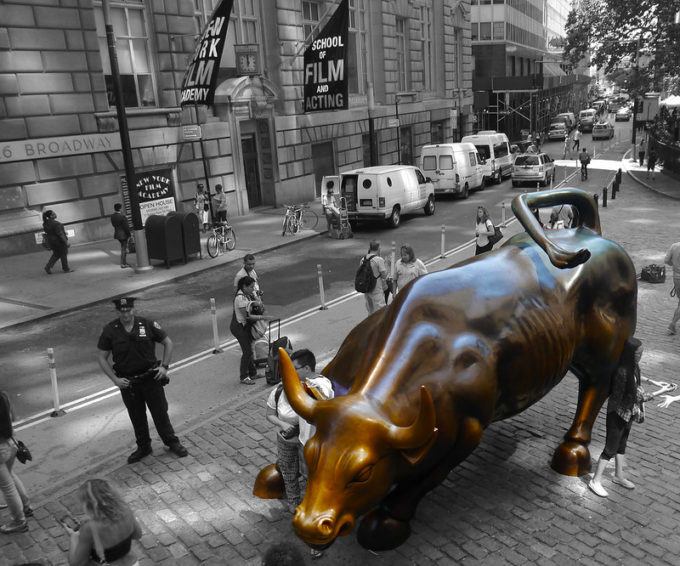

Photograph Source: concrete&fells – CC BY 2.0

For more than two decades, the general counsels of Wall Street’s megabanks have been meeting together secretly once a year at ritzy hotels and resorts around the world. This would appear to be a clear violation of anti-trust law but since Wall Street’s revolving door has compromised the U.S. Department of Justice over much of that time span, there has been no pushback from the Justice Department to shut down these clandestine meetings.

Wall Street insiders say that among the top agenda items at this annual confab are strategy sessions on how to keep Congress from enacting legislation that would bring an end to Wall Street’s privatized justice system called mandatory arbitration. This system allows the most serially corrupt industry in America to effectively lock the nation’s courthouse doors to claims of fraud from its workers and customers. This private justice system also keeps the details of many of Wall Street’s systemic crimes out of the press.

Wall Street’s McJustice system is just one element of a fully-loaded dirty tricks playbook that Wall Street uses to crush an honest worker who is intent on holding the firm to account. The playbook includes gaslighting; a campaign of ordered ostracizing by coworkers; demotion; an internal investigation with a preordained outcome to malign the reputation of the whistleblower; blackballing in the industry; and, frequently, the ultimate humiliation of being escorted out of the building by security guards. As the dirty campaign unfolds in front of colleagues, it achieves the intended additional goal of silencing any coworkers who might be thinking about reporting illegal activities.

Following this psychological warfare inside the Wall Street firm, the honest whistleblower will be met with the next chapter of the sociopathic playbook: Wall Street’s star chamber (mandatory arbitration) tribunals if he or she attempts to get compensated for damages, lost compensation and so forth. The Wall Street firms frequently bring current employees who were friends with the fired whistleblower to testify to outrageous lies about the honest worker in an effort to inflict more emotional damage to ensure this individual will look for future employment anywhere but Wall Street.

In one particularly brazen example of how this private justice system functions outside of the law, JPMorgan Chase employees felt confident that they could get away with falsifying written customer complaints against an honest whistleblower, broker Johnny Burris, and enter them at his arbitration hearing before the industry’s self-regulator, FINRA. Burris had earned the wrath of the bank for having the temerity to tape-record his bosses pressuring him to sell the firm’s own mutual funds to his clients, which generated more profits for the bank, rather than being allowed to decide which mutual funds would properly serve his clients’ best interests.

Burris was not the only honest whistleblower to use tape recordings as a means of securing a factual archive of events against Wall Street’s retaliatory lies. Carmen Segarra was an attorney and bank examiner employed by the New York Fed, a thoroughly captured regulator. She was deployed at Goldman Sachs. After she was bullied by colleagues (aptly called “relationship managers”) to change her negative examination of Goldman, she went to the Spy Store in lower Manhattan and bought a tiny microphone and recorded 46 hours of audio that demonstrated just how compromised by Wall Street the New York Fed had become. Segarra was fired after she refused to change her negative examination of Goldman.

Because Segarra was a bank examiner, she filed a lawsuit in federal district court in Wall Street’s stomping ground, the Southern District of New York, asserting a violation of protected activity as a bank examiner under the Federal Deposit Insurance Act. The case was dismissed by Judge Ronnie Abrams, who was married to Greg Andres, a partner at law firm Davis Polk & Wardwell. The case was before the court from October 2013 until April 3, 2014 when Judge Abrams scheduled a telephone conference with both sides to share the pesky detail that “it had just come to her attention that her husband [wait for it] was representing Goldman Sachs in an advisory capacity.” The Judge did not recuse herself and dismissed Segarra’s case.

Segarra courageously served the public interest by taking those 46 hours of tapes and her story to investigative reporters at ProPublica and public radio’s This American Life. What has happened to Goldman Sachs since then? On October 22, 2020 the Justice Department charged Goldman Sachs and its Malaysian subsidiary each with one felony count for “engaging in a scheme to pay more than $1.6 billion in bribes, directly and indirectly, to foreign officials…” in order to secure business for Goldman Sachs.

Segarra has plenty of company when it comes to honest attorneys who have become the target when they push too hard to hold powerful Wall Street titans or firms accountable. Former SEC attorney Gary Aguirre testified before the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary in June 2006 about how trying to do his job with honesty derailed his career at the SEC. During Aguirre’s tenure at the SEC he had pressured his superiors to serve a subpoena on John Mack, a powerful former official at Morgan Stanley. Aguirre wanted to take testimony about Mack’s potential involvement in insider trading. What happened instead was that Mack was protected and Aguirre was fired over the phone while on vacation. The termination looked particularly suspicious because just three days prior, Aguirre had contacted the Office of Special Counsel to discuss the SEC’s protection of Mack.

More sadistic shenanigans from Wall Street’s dirty tricks playbook have spilled out this year in two federal lawsuits filed against JPMorgan Chase. In an amended complaint filed on June 23 by Donald Turnbull, a 15-year employee of the bank who had risen to the rank of Managing Director, he told the court that he had been fired for “cooperating in good faith with a federal investigation into the Bank’s trading practices.”

According to Turnbull’s lawsuit, once JPMorgan Chase “learned the nature of the information Mr. Turnbull had shared with government prosecutors — JPMorgan launched a retaliatory campaign against Mr. Turnbull. Alarmed by the perception of its institutional culpability, JPMorgan hurried through a faux inquiry into Mr. Turnbull’s unimpeachable trading practices. Based on a pretextual narrative that the Bank had lost confidence in him, the Bank terminated him, cancelled his unvested stock, and threatened to claw back his prior compensation.”

Less than five months after Turnbull filed his federal lawsuit, Shaquala Williams, a female attorney who worked in compliance at JPMorgan Chase, filed her own lawsuit in the same federal district court in Manhattan for whistleblower retaliation for protected activities under the Sarbanes-Oxley Act of 2002. (Whistleblower retaliation claims can sometimes avoid the mandatory arbitration trap and be sustained in federal court.) Williams makes extremely serious charges, alleging that the bank was effectively keeping two sets of books so it could make “emergency” payments to third party intermediaries, one of whom was a former government official tied to Jamie Dimon, the bank’s Chairman and CEO. Williams also claims that the bank had set up sham controls that violated its non-prosecution agreement with the Justice Department. (See the full text of Williams’ federal complaint here.)

An equally disturbing story comes from Peter Sivere, who spent the majority of his career as a compliance official at two mega banks on Wall Street attempting to get his superiors to acknowledge the internal misconduct he reported, first at JPMorgan Chase and then at Barclays. JPMorgan Chase, which has subsequently admitted to an unprecedented five felony counts brought by the Justice Department between 2014 and 2020, had security guards humiliate Sivere by escorting him out of the building. Barclays first demoted Sivere, then terminated him.

The Board of Directors of JPMorgan Chaseappears to be an enabling component of the dirty tricks playbook. Since 2014, the Board members have been reading about unfathomable levels of crime inside the bank they oversee but they have kept the same Chairman and CEO, Jamie Dimon, at the helm of the bank throughout that period. Less than 10 months after the bank admitted to its fourth and fifth felony counts on September 29, 2020, JPMorgan’s Board handed Dimon not a pink slip but a $50 million bonus. That gives a whole new level of meaning to Senator Bernie Sanders’ oft repeated message that “the business model of Wall Street is fraud.”

Wall Street veteran and writer, William Cohan, has written extensively about Sivere’s dogged efforts in articles at Bloomberg News in 2012, the Financial Times in 2014 and the New York Times in 2015. One might think that this kind of media exposure would bring some kind of closure to Sivere. It hasn’t. That’s because both Sivere and his attorney, Oliver Budde, believe justice has been ill served in this matter.

We offered attorney Budde the opportunity to explain his theory of Sivere’s case for our readers. He provided us with the following statement:

“I see a conspiracy among Barclays, Sullivan & Cromwell and DOJ [Department of Justice] to bury the truth that in 2011, as a Barclays compliance officer, Peter Sivere blew the whistle on some Barclays employees misappropriating confidential information provided by client Hewlett-Packard in regard to foreign exchange — the very misconduct that seven years later became the basis for a 2018 letter agreement whereby DOJ declined to prosecute Barclays for the misconduct, in exchange for Barclays enhancing its compliance program, cooperating with DOJ and paying $12.9 million. Sullivan & Cromwell, Barclays’ outside counsel, also signed that letter. In it, DOJ with Sullivan & Cromwell’s endorsement gave Barclays special credit for ‘timely, voluntary self-disclosure’ in 2016 of precisely what Sivere had flagged to Barclays five years earlier in 2011. But in 2011, Barclays preferred to continue the wrongdoing rather than address it. So instead, Barclays decided essentially to ruin Sivere’s life, and so far, so good.

“The conspiracy appears quite daring, if not reckless, because Sivere is on record repeating his concerns to various audiences both inside and outside Barclays from 2013 to 2015, including to the New York Times in August 2015. We have abundant evidence that DOJ, Sullivan & Cromwell, the Barclays Board of Directors, CEO Antony Jenkins, Head of Compliance Hector Sants, and many others at Barclays all knew of Sivere’s 2011 whistleblowing by 2015. We have evidence that Sivere participated in a 2015 teleconference with DOJ and FBI personnel, and Sivere swears in an affidavit that he described his 2011 Hewlett-Packard concerns on that call. And finally, Alexander Willscher, the very Sullivan & Cromwell attorney who signed the 2018 DOJ letter, was one of four Sullivan & Cromwell recipients of dozens of emails Sivere sent in 2015 in which he again explained those concerns at length.

“Why bury the truth of Sivere’s 2011 whistleblowing? Simple: in June 2012 Barclays signed a similar letter agreement in which DOJ declined to prosecuteLIBOR misconduct, which obliged Barclays to report ‘all potentially criminal conduct by Barclays or any of its employees that relates to fraud or violations of the laws governing securities and commodities markets.’ Likewise, in May 2015 Barclays signed a plea agreement with DOJ wherein DOJ declined to prosecute foreign exchange misconduct, but with no mention of Hewlett-Packard, which similarly obliged Barclays to report ‘all credible information regarding criminal violations of U.S. law concerning fraud, including securities or commodities fraud by the defendant or any of its employees as to which the defendant’s Board of Directors, management (that is, all supervisors within the bank), or legal and compliance personnel are aware.’

“If Barclays, Sullivan & Cromwell, or DOJ were ever to admit the validity of Sivere’s 2011 whistleblowing, then it would become clear that Barclays had violated the terms of both the 2012 DOJ letter agreement and the 2015 DOJ plea agreement, and nobody could credibly claim that Barclays deserved either the mild treatment or the special credit for ‘timely, voluntary self-disclosure’ afforded to it by the 2018 DOJ letter agreement.

“I am ready to defend my assertions in any appropriate forum.”

Let’s pause here to reflect for a moment. There is now an attorney whistleblower, Shaquala Williams, filing a lawsuit in federal district court in Manhattan in which she asserts that JPMorgan Chase is effectively making a monkey out of the Justice Department by issuing sham reports of its compliance with its non-prosecution agreement. Now we have another attorney, Oliver Budde, willing to put his name to a statement that there’s a conspiracy surrounding Barclays’ non-prosecution agreement with the Justice Department.

Maybe it’s time for an independent Special Counsel to be appointed to investigate these non-prosecution agreements. We learned through Frontline’s investigation about how Obama’s Justice Department was investigating Wall Street’s crimes from the 2008 financial crisis. Frontline reported that there were “no investigations going on. There were no subpoenas, no document reviews, no wiretaps.”

There are a number of additional reasons to take attorney Budde’s theory of the case seriously. First, the Justice Department, under both the Obama administration and the Trump administration, has been handing out non-prosecution agreements to serial lawbreakers on Wall Street like it’s a meter maid handing out parking tickets for failing to put enough quarters in the meter. Clearly, a recidivist lawbreaker does not deserve endless probation agreements.

Secondly, one of the attorneys who signed the 2018 non-prosecution agreement on behalf of Barclays was Andrew Willscher, a Sullivan & Cromwell partner who brags on the law firm’s website about persuading the Justice Department in the 2018 deal “not to bring criminal charges against Barclays relating to allegations that bank employees used confidential merger information to front-run trades and enable the bank to profit at a client’s expense.” Willscher also brags about the 2015 non-prosecution agreement where he represented Barclays “in the investigation and resolution with the DOJ and other regulators relating to a criminal conspiracy to manipulate the price of currency exchanged in the global FX Spot Market.” The 2015 case included evidence of a Barclays trader stating in a chat room “…if you ain’t cheating, you ain’t trying.”

Should Willscher, an attorney, be bragging on his law firm’s website about getting a serial repeat offender off the hook for prosecution?

While Willscher was settling the 2018 Foreign Exchange trading/front running matter with the Justice Department, a Sullivan & Cromwell law partner, Jay Clayton, was sitting as the Chairman of the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), thanks to his nomination by President Donald Trump. Another Sullivan & Cromwell law partner, Steven Peikin, was serving as Co-Director of the SEC’s Division of Enforcement.

Peikin is the Sullivan & Cromwell partner who had negotiated the Barclays non-prosecution agreement in 2012for Barclays’ involvement in rigging the interest rate benchmarks, LIBOR and EURIBOR, and the amended agreement of 2014. Peikin’s name appears on both agreements.

As we reported when Clayton was nominated to be SEC Chair, he had represented 8 of the 10 largest Wall Street banks in the prior three years at Sullivan & Cromwell. Clayton was too deeply conflicted to be nominated, and yet, he was confirmed anyway.

We asked Tom Mueller, author of the seminal work on corporate whistleblowers, Crisis of Conscience: Whistleblowing in an Age of Fraud, what he thought of the regulatory situation on Wall Street today. Mueller responded:

“The line of goods we’ve all been sold, that lawyers who regulate Wall Street can freely leave their posts to join Wall Street banks or their white-shoe defenders – that cops can morph into robbers without impairing their will to police – is the single most toxic characteristic of Good ol’ Boy financial pseudo-regulation in America. The revolving door acts like a cup of polonium-laced tea on the professional ethics of attorneys in the financial services.”

When Bloomberg News reported in 2016 about the General Counsels of Wall Street mega banks meeting in secret annually for two decades, we noted that attendees at the clandestine 2016 meeting included Stephen Cutler of JPMorgan Chase (a former Director of Enforcement at the Securities and Exchange Commission); Gary Lynch of Bank of America (a former Director of Enforcement at the SEC); and Richard Walker of Deutsche Bank (also a former Director of Enforcement at the SEC).

Another smoking gun from the 2018 non-prosecution agreement between Barclays and the Justice Department is that the investigation into the foreign currency frontrunning at Barclays was not handled by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (CFTC), which states on his website that it is “the Federal agency with the primary responsibility for overseeing the commodities markets, including foreign currency trading.” Nor was the investigation overseen by the Securities and Exchange Commission, which could have investigated Sivere’s allegation that Hewlett-Packard’s confidential information was improperly shared at Barclays to financially benefit Barclays’ proprietary trading.

Instead, bizarrely, the Inspector General of the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) conducted the investigation. The last paragraph of the press release announcing an indictment in the matter reads as follows:

“The investigation is being conducted by the FDIC’s Office of Inspector General. Assistant Chief Brian Young and Trial Attorney Justin Weitz of the Criminal Division’s Fraud Section are prosecuting the case. The U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of California provided substantial assistance in this matter.”

The FDIC Office of Inspector General acknowledges on its website that it has “broad jurisdiction to investigate crimes involving FDIC-regulated and insured banks and FDIC activities.” An indictment in the case was brought against an employee of Barclays Capital Inc., a brokerage firm (broker-dealer) that has nothing to do with the insured deposits overseen by the FDIC.

The story gets even stranger. We emailed the FDIC OIG’s Media Relations contact three times attempting to learn how the FDIC OIG became involved in this trading matter that would properly belong with the CFTC and SEC. We simplified our question in our third attempt to this: “Under what circumstances would the FDIC OIG be authorized to conduct an investigation involving a broker-dealer’s Foreign Exchange Trading, when its public mandate is to investigate matters pertaining to federally-insured banks?”

The media relations person provided no responsive answer, just a link to the FDIC OIG’s main website.

Barclays may now be in hot water with Wall Street’s self-regulator, FINRA. According to Sivere, the separation agreement he signed with Barclays required him to arbitrate any future claims he might have against Barclays before a private arbitration forum known as JAMS. This appears to be another page from the dirty tricks playbook.

Sivere worked for Barclays Capital, a brokerage firm (broker-dealer). As a compliance official, he fell into the category of what Wall Street’s self-regulator, FINRA, defines as an “Associated Person.”

We asked FINRA via email if a broker-dealer is allowed to use a private arbitration forum rather than FINRA’s forum for disputes between an Associated Person and his firm. We let FINRA know that we were specifically speaking about a compliance official at Barclays whose separation agreement called for the exclusive use of JAMS.

Unlike the FDIC OIG, which went into hiding when we posed a question, we promptly received a detailed response from FINRA. It included this rather stark assessment of the substitution of JAMS instead of FINRA Dispute Resolution:

“Thus, FINRA considers actions by member firms that require associated persons to waive their right under the Industry Code to arbitration of disputes at FINRA in a predispute agreement as a violation of FINRA Rule 13200 and as conduct inconsistent with just and equitable principles of trade and a violation of FINRA Rule 2010 (Standards of Commercial Honor and Principles of Trade).

“FINRA notes that it has a statutory obligation under the Exchange Act to ‘enforce compliance by its members and persons associated with its members, with the provisions’ of, among other things, the Exchange Act and FINRA’s rules, which include the requirement to arbitrate before FINRA. Furthermore, FINRA may sanction its members or associated persons for violating any of its rules by ‘expulsion, suspension, limitation of activities, functions, and operations, fine, censure, being suspended or barred from being associated with a member, or any other fitting sanction.’ ”

We contacted Barclays seeking a response to FINRA’s interpretation of what Barclays had done by substituting JAMS. We also asked how many other separation agreements Barclays had written that exclusively designated JAMS as the arbitral forum. We received this response: “We will decline to comment on this.”

According to an article in the Los Angeles Business Journal in July of last year, JAMS’ structure works like this: it is owned by 125 of its arbitrators/mediators who are considered independent contractors and can set their own rates, “which range from about $6,000 to $15,000 a day, with an average of about $10,000 to $11,000 a day, according to one industry executive.” The article also reported that JAMS’ retired judges account for about 75 percent of JAMS arbitrators/mediators and they can take home 70 to 75 percent of their fees.

We contacted JAMS via email asking if there was anything inaccurate in the above information that has been published on the website of the Los Angeles Business Journal for more than a year. We received no response.

Last September, Sivere filed an arbitration with JAMS, essentially on the basis of the theory outlined above by his current attorney Budde. Sivere had a single arbitrator for his case, Carolyn Demarest, a former Presiding Justice of the Commercial Division of the Supreme Court of Kings County, New York. Demarest billed at $775 an hour, rivaling the lawyers at Wall Street’s Big Law firms. Sivere provided us the invoice, indicating that he paid in excess of $10,500 while Barclays paid a similar, but smaller, amount. Demarest dismissed the case on a Motion for Dismissal from Barclays.

In a federal court case, both the Judge and the jury are provided at no cost to the plaintiff and are paid for by the U.S. taxpayer. Wall Street has convinced federal courts across America that mandatory arbitration is “fair, fast and cheap.”

The American Association for Justice released a study on October 27, which analyzed the consumer and employee win rate at private arbitration forums JAMS and a similar group, the American Arbitration Association (AAA). The study found the following:

“In years past, consumers were more likely to be struck by lightning than win a monetary award in forced arbitration. In 2020, that win rate dropped even further. Just 577 Americans won a monetary award in forced arbitration in 2020, a win rate of 4.1% — below the five-year-average win rate of 5.3%. For employees forced into arbitration, the likelihood of winning was even lower. Despite roughly 60 million workers being subject to forced arbitration provisions at their place of employment, just 82 employees won a monetary award in forced arbitration in 2020.”

The five-year average win rate for employees going before JAMS and AAA arbitrations was 1.9 percent.

This story first appeared on Wall Street on Parade.