His life was lived in time of war, plague, and famine. He did not shelter in place.

No music was cloaked more darkly in the allure and peril of travel than that of the enigmatic seventeenth-century keyboardist Johann Jakob Froberger (1616-1667). Commemorating encounters, incidents, and personages from across Europe, Froberger’s oeuvre acquired its lasting aura not only through its unmistakable approach to harmony and gesture, but also because the uniqueness of his style was tied to the legend of an extraordinary life chronicled, if episodically, in his suites, as well as in the contrapuntal genres of the Fantasia, Capriccio, and Ricercar inspired by his Italian sojourns. Froberger’s student, Balthasar Erben described his teacher as “well-traveled”—an understatement the combined reverence with irony.

Froberger’s path took him to the great European capitals for study, competition, command performances at Imperial diets, perhaps even diplomatic intrigues. The impressive circuit of cities which included Rome, Paris, Vienna, Dresden, London, Brussels, Utrecht, has been extended to Madrid. According to a presentation manuscript from Froberger’s own hand auctioned in 2006 at Sotheby’s that fetched upwards of half-a-million-dollars, the hitherto unknown Meditation on the future death of his patroness Duchess Sibylle of Württemberg-Montbéliard was composed in Spain towards the end of Froberger’s life. The dedicatee would outlive the composer.

Froberger’s journeys brought him into contact with many celebrated musical figures of the age, not to mention polymaths of European standing, Constantijn Huygens and Mersin Mersenne. Froberger was heard by Governor of the Spanish Netherlands, numerous Italian Princes, the English King, three Holy Roman Emperors, and a Saxon Elector. Great historical moments—from the election and death of emperors to the movements of Cardinal Mazarin in and out of Paris—provided the panoramic canvasses on which his musical essays were rendered in the personal, idiosyncratic manner of an inveterate traveler of restless imagination. Froberger’s peregrinations were woven into his music, not only through the use of autobiographical annotations and subtitles, but in the details and shape of his inimitable style.

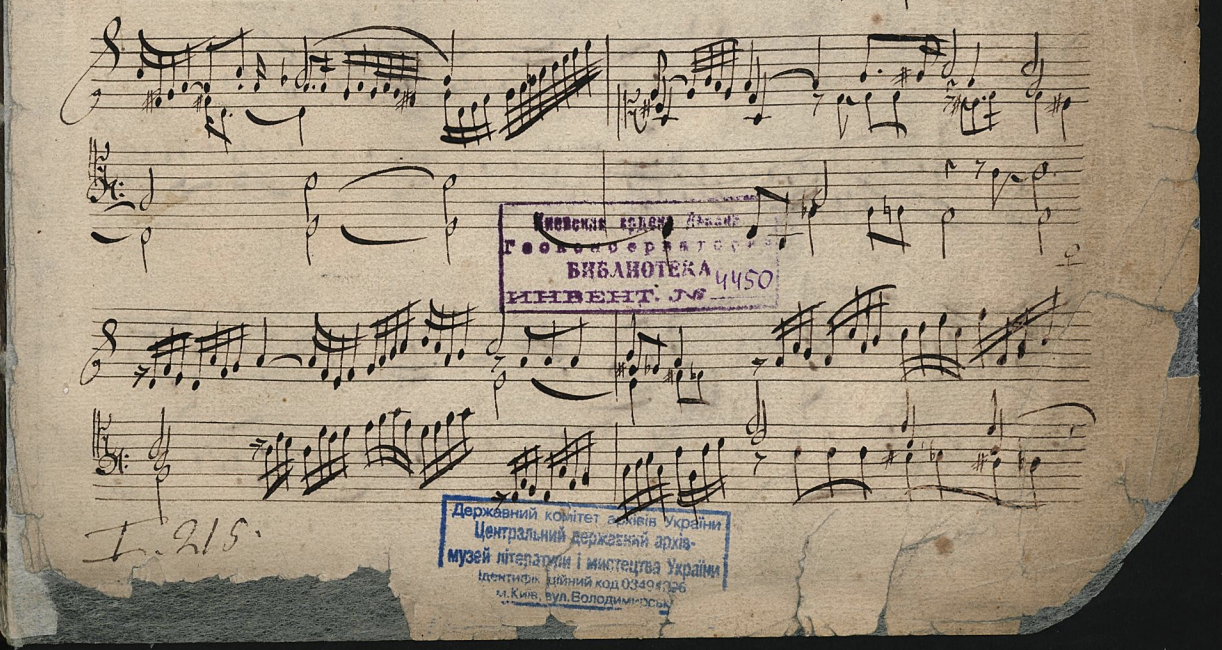

The most elaborate of Froberger’s annotations are found in a manuscript looted by the Red Army in 1945; this volume was rediscovered along with much precious material from the Bach family and other composers in 1999 in Kiev, and subsequently returned to the State Library in Berlin. The first page of manuscript is marred by two Soviet war-booty stamps in rude purple and blue that clash in shape and color with the black ink and flowing hand of the notes and staves. These rectangles look like marks in a passport documenting a half-century sojourn in an Ukrainian basement, likely the eastern-most port of call for Froberger’s music.

Leafing through these musical travel papers we encounter the geographical landmarks of the continent: the Rhine River, the Alps, the English Channel; the capital cities, London and Paris and Vienna, seat of the Imperial Court.

Among the misadventures chronicled by Froberger’s music and prose, his crossing of the English Channel comes alive most vibrantly in the Age of Brexit with its the fears of immigration to the island kingdom. After being robbed on the road from Paris to Calais, Froberger embarks on a the ship that is raided. Broke and bereft, he turns up in London “full of sorrow in thrown-together seaman’s clothing.” He finds work pumping the bellows for the court organist, but raises them too high and is promptly beaten by the organist. This drubbing will move Froberger to compose the Plaincte fait à Londres pour passer la Melancolie (Plaint composed in London to overcome melancholy).

Like all inveterate travelers Froberger must rely on his skills for improvisation; he survives by thinking on his feet and with his hands. During a break in the music making, with the wind quickly leaving the organ’s bellows, the now-or-never moment is upon the beleaguered traveler. The account reports that Froberger “grabbed a dissonant chord and then resolved it to pleasing concord.” The flourish is immediately recognized by a foreign lady, who, in one of those coincidences typical of fairy tales, plays, and operas, had studied with the visitor back on the continent. The king is informed of the presence of the illustrious Froberger, and a harpsichord is promptly produced for his immediate apotheosis. The musician duly astonishes the royal gathering. The turn-around from beggar to honored foreign virtuoso occurs abruptly and completely. Like the prince in rags, his true character cannot be obscured by his clothes.

Most remarkable, not only because of its length but also because of its detail, is the literary text for an Allemande “composed in traveling the Rhine.” In the Berlin manuscript repatriated from Kiev twenty-six actions are fitted into a mere sixteen measures of music; these happenings are marked by numbers placed above each system and then described in detail in the annotation below.

The Allemande presents perhaps the most lopsided proportion of words to notes of any such descriptive attempt. A little music could be made to mean much by Froberger. The text describes an incident, which took place during a journey down the central artery of European travel, the Rhine River. The Rhine was a crucial juncture and symbol in any traveler’s lifetime, as defining geographically and psychologically as the English Channel and the Alps, both of which were similarly inspired, or perhaps provoked, Froberger’s musical imagination.

The Allemande’s program tells us that “Count von Thurn wishing to travel on the Rhine, from Cologne to Mainz, along with several other gentlemen, among whom were his major domo Monsieur Mitternacht, two Mssrs. von Ahlfeldt, Monsieur Bodeckh, and Froberger, this little company made merry at St. Goar, to such an extent, that it lasted until the around three o’clock toward daybreak on Midsummer Eve, the 24th of June; but when they returned to the ship, completely worn out, at five o’clock, each sought out a place, where he wished to sleep. Monsieur Mitternacht, being last, had to take a spot in the skiff, the ship being already fairly full. Lest his dagger disturb his sleep, he sought to hand it to the crewman, who was unable, however, to reach it from the big ship; whereupon Monsieur Mitternacht, although holding fast with one hand to the big ship, which was constantly moving about, leaned too far over the skiff, and, owing to the weight of his body, fell unexpectedly into the water. Not only did this occasion great confusion aboard the ship, so that the one ran this way, the other that, creating a commotion hither and thither on board, but Monsieur Ahlfedlt the Elder was the first, followed by Monsieur Bodeckh, and Monsieur Ahlfeldt the Younger does not hesitate either. Now Count von Thurn, not wishing to be last, runs about on the ship in great fury, and leaps down into the skiff to rescue himself. The crewmen arrive to reach him with the little skiff, but to no avail, so that Monsieur Mitternacht begins to groan. Froberger too awakens at last, and perceiving that there is no one lying beside him, concludes nothing less, than that the ship is about to be wrecked. As there is nobody to help him, he resolves, upon hearing the cries and howls of the others, to drown slowly and with good grace, and begins to commend his spirit to God, that He might be merciful. Meanwhile the crewman (No. 10) tries to prove his mettle, by pulling [Monsieur Mitternacht] out with the long pole, on which is fashioned a hook; but in vain, merely succeeding in tearing his modish French coat. Monsieur Mitternacht now begins to swim, but with such difficult, that he lands in a pretty pass, and is forced by exhaustion (No. 13) to rest a little, as well as he might. Believing himself to be out of harm’s way, he lands (no. 14)in the whirlpool and begins to thrash his feet. Escaping the whirlpool with great effort, and forcing himself upward, he is again spotted by the crewman, who diligently returns with the long pole to rescue him, but gives him such a vicious blow across the shoulder with the same, that it was heartrending to behold. In great pain, [Monsieur Mitternacht] is forced to cry out in a loud voice, yet most lamentably ò Dio, ò Dio mio, and resolves forthwith to swim through the Rhine. But so swift is the current that he is drawn under, making him fairly lose heart, and he commends his soul to the Lord. As the current draws him deeper and deeper into the depths, he heaves a few more sighs to God, that He might rescue him’ which sighs, finally the Lord graciously deigns to hear, so that, contrary to all hopes, he is reached by the crewman, who was on the skiff, and is thus heaved into the skiff, his life rescued, one might say, as booty.”

Each misstep in this classic near-debacle of the seventeenth-century traveler is accounted for in the music. The scene is set at the dangerous rapids of St. Goar on Midsummer night, a time of revelry augmented by the town’s traditions of drink. Visitors to St. Goar put their heads through a brass ring set into the masonry of the embankment, then were asked if they wanted to be baptized with water or wine. Those who opted for wine had to treat their traveling partners to a round of drinks; those who chose water were immediately doused with a bucket pulled from the river.

The dangers of the Rhine at St. Goar were warned of in many travel books echoed in the portentous allusion of the Allemande’s subtitle to “great peril.” Still, the piece is no a thriller. Rather Froberger steps back from the events described and presents them as a cautionary tale, the action slowed for the re-telling. The furious early morning struggle against the Rhine at Midsummer is recast in a twilight of brooding contemplation. Pained disquiet alternates with poised reflection, as if the one is not possible without the other.

The turn towards death in the literary text of the Allemande shadows nearly all of the opening movements of Froberger’s suites in the Kiev manuscript, from the melancholic London Plainte to the manuscript’s other Meditations and Laments. The “Lament on that which is taken from me” (Lamentation sur ce que j’ay esté vole) was composed after Froberger was ensnared in the Fronde conflict, a grim coda to the Thirty Years’ War in France and along its borders. As he makes his way from Brussels to Leuven, Froberger is whipped by soldiers and his passport stolen. The incident elicits from him yet another plaint, composed far from home and in low spirits. The Lamentation does not refer to stolen possessions but to the degradation of the spirit: it is not simply the physical abuse that causes Froberger’s despondence, but the enduring humiliation. The performance direction describes the piece as an attempt to use the abstraction of art to overcome brutal physical reality: “To be played freely, and better than the soldiers treated me.”

So many brushes with death must have encouraged Froberger’s obsessive reflections on mortality. There is a large body of thought that interprets the incessant need of many to travel as driven by a fear of death. On the road again, now late in life, the Meditation on my future death (Meditation faite sur ma mort future) was composed in Paris. In the manuscript Froberger noted the very date and place of composition: the traveler commits these thoughts to paper on May Day, contemplating his death when Paris was celebrating the return of life with spring. Death lurks everywhere and is faced resolutely by our musical narrator and travel guide, Froberger, whether on the Rhine or in his rooms in distant Paris.

And how do we explain the devastating question mark added after the traveler’s name at the bottom of the page of the Paris Plaint: “Memento Mori Froberger?” After the music and the life it tells of comes the silence of oblivion. The composer confronts it at what could well be the end station of the earthly itinerary.

Yet Froberger’s fame and music did outlive him, in spite of his own efforts to restrict the posthumous circulation of his manuscripts. An invitation to flee local circumstance, Froberger’s music fed both the musical and geographical imaginations of his followers, including the young J. S. Bach, who clandestinely copied out his music by moonlight.

Froberger’s meditations on travel and existence are delivered in the intimate terms of personal revelation, like a diary written in the familiar, if haunting, rhetoric of a noble character, recognizable in style but no less mysterious, even baffling for its uncanny familiarity. This traveler’s voice echoes into our own time and place, telling us that Froberger’s musical journeys are still underway.