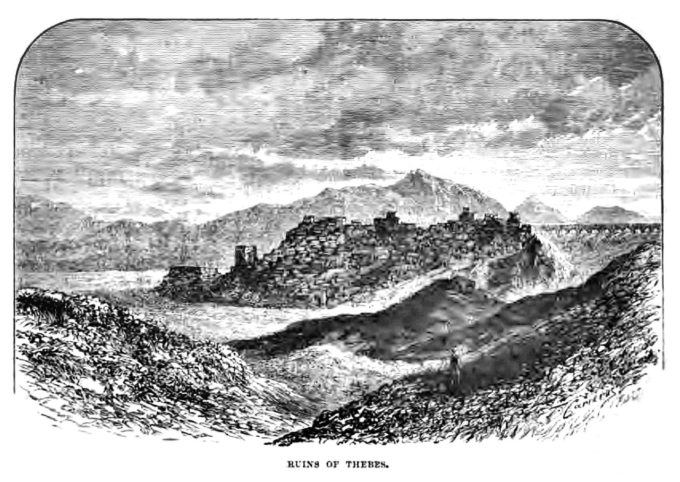

Ruins of Thebes, Cassell’s History of the World (1882).

Thebes was one of about 1,000 poleis (city-states) spread all over the mainland of classical Greece, the islands of the Aegean and Ionian seas, the Black Sea coast, Asia Minor, north Africa, southern France, eastern Spain and southern Italy and Sicily.

There were so many Greeks and Greek city-states in Italy and Sicily the Romans described the region as Magna Graecia. Plato used to joke that the Greeks were like frogs playing in a pond, the Mediterranean. He ignored the Black Sea pond.

Surrounded by Athens and Sparta

Thebes, along with Athens and Sparta, was unusual. It was a relatively strong polis in central Greece or Boeotia, continuously inhabited for five millennia. Yet Thebes’ more powerful neighbors, Sparta and Athens, and, in the fourth century BCE, Macedonia, made the life, the historical life of Thebes unpleasant to the extreme. Thebes almost disappeared from history. Athenians often called Thebans Boeotian swine.

But the Thebans were not swine. They were at the heart of Greek culture. The fatal error of Thebes was to side with the Persians in 480 BCE while the multitudes of King Xerxes threatened the very survival of Hellas. Sparta, Athens and Macedonia never forgot that treason.

Yet 400 Theban fighters fought with King Leonidas and his small number of hoplites against the Persians in the heroic battle of Thermopylae in August 480 BCE.

Olympics in the midst of carnage

This was not the only surprise: 480 BCE was the year of the Olympics. And despite the Persian danger, the games went on. Hellas was flooded by enemy Persians slaughtering Leonidas and  his brave soldiers at Thermopylae and then they burned Athens.

his brave soldiers at Thermopylae and then they burned Athens.

By that time, August 480 BCE, athletes and thousands of Hellenes were in Olympia for the games. Athletes came from Thebes hosting Persians, Argos that stayed “neutral,” Syracuse and other poleis of Magna Graecia and the Aegean islands of Thasos and Chios. Athens and Sparta were fighting and sent no athletes to the Olympics.

The celebrated pentathlon athlete Phayllos of Kroton in southern Italy did not compete in the 480 BCE Olympics. Instead, he funded and led a warship, which fought in the battle of Salamis in September 480 BCE. The Athenians honored him with a statue on the Acropolis.

Thebes was part of that Hellas in mortal danger. Few people could have foreseen the results. We don’t know why the leadership of Thebes chose Persia. It could be fear of Persians or hatred for Sparta and Athens. Hundreds of other Greek states stayed out of the Hellenic union against Persia. Myths may also have had something to do with the history of 480 BCE.

Thebes of hero-gods and poetry

In the case of Thebes, myths and history often tangled with each other, enriching Greek drama, poetry, life and civilization.

After all, despite 480 BCE, this was the polis of two hero-gods, Dionysos and Herakles, both of enormous importance to all Greeks and their civilization. In addition, Thebes was the homeland of the great epic poet Hesiod, nearly of equal status with Homer, the giant of Hellenic epic poetry and civilization. The great lyric poet Pindar was Theban as well.

Oedipus: madness and revenge

Oedipus (Oidi-Pous, Swell-Foot) was another inhabitant of Thebes. He solved the riddle of the Sphinx: that man had four feet in the morning, two in the afternoon, and three in the evening.

Oedipus’ intelligence served him badly. It made him king, but unleashed a series of calamities for himself and his family and Thebes. Oedipus did not know that as a baby his royal Theban parents had given him to a shepherd for exposure and death because of a horrific Delphi oracle predicting an adult Oedipus, the man who won over the terrible Sphinx, would marry his mother and kill his father.

So, Oedipus did kill his father Laios and married his mother Iokaste. His two sons, Eteokles and Polynikes, fought a bitter civil war and killed each other with their own hands. Their sister, Antigone, died defending divine tradition over the law of the tyrant Kreon, brother of Iokaste. He forbade the burial of Polynikes bur Antigone defied him, burying her brother.

This legacy of divine wrath informed humans of the unforgettable crimes of killing one’s parents and marrying within the family. The Oedipus tragedy inspired immortal plays by the Athenian tragic poets Aeschylos and Sophocles. Aeschylos composed Seven Against Thebes and Sophocles wrote Antigone.

Thebes’ short-lived supremacy

Historical Thebes was no less exciting. In the fourth century BCE, Thebes became a superpower in the Greek world. It put Sparta out of its military business in its crushing and decisive victory in the battle of Leuktra in 371 BCE. This was unprecedented in Greek history. Sparta, the Greek superpower of early fifth century BCE, lost half of its territory and all its Helots raising its food.

The result of Leuktra raised Thebes to the pinnacle of political power in Hellas. Thebes ordered Greek politics to its liking. Then Alexander the Great annihilated Thebes in 335 BCE. He probably remembered that Thebans fought on behalf of the armies of Xerxes against Hellas in 480 BCE, and that Thebes kept his father Philip under house arrest from 368 to 365 BCE.

The kingdom of myth and the Phoenician prince Kadmos

It all started with a mythic migrant prince from Phoenicia (Lebanon) named Kadmos. We are supposed to believe that this foreign prince founded Thebes. He sowed the land with dragon’s teeth and harvested Sown-Men (Spartoi) warriors, ready for war and for building the city.

But the immigrant Phoenician did not come to Boeotia simply to build a city. His goal was to find his sister Europa who was so beautiful she attracted Zeus, the greatest and mightiest of the Greek gods. Zeus sent a gorgeous white bull to the playground of Europa. The bull lured her to ride him and then, effortlessly, carried her to Crete where Zeus made love to her and Europa gave birth to three sons: Minos, Rhadamanthys, and Sarpedon.

The sons did well for themselves. Rhadamanthys became the immortal judge of the dead in Hades. We don’t know the future of Sarpedon. But Homer talks about another Sarpedon, son of Zeus and Laodameia, daughter of the hero Bellerophon, possibly son of Poseidon. This Homeric Sarpedon went down from the spear of Patroklos, friend of Achilles, the greatest Greek hero of the Trojan War.

As for Minos, he triumphed. He became the king of Crete in the second millennium BCE, indeed he was so famous, the brilliant civilization of Crete took his name: Minoan.

The bull became the constellation Taurus and Europa gave her name to Europe.

Kadmos did not find Europa. He became another Greek hero. He is supposed to have married Harmonia, daughter of the war god Ares and the goddess of love Aphrodite. Kadmos gifted Harmonia with a necklace made by the god of craftsmanship and metallurgy Hephaistos. The Greek gods even showed up to his wedding.

His daughter, Semele, like his sister, Europa, was too beautiful to escape the attention of Zeus. But Semele foolishly demanded that Zeus presents himself to her in his real divine nature. Reluctantly, Zeus did and Semele disappeared like a flash of lightening. Zeus, however, saved his son Dionysos from the burning body of Semele, inserting the fetus Dionysos into his thigh for nourishment. Eventually, Dionysos / Bacchos made Thebes his permanent home.

A grandson of Kadmos, King Pentheus, was offensive to Dionysos. The blind Theban seer Teiresias warned Pentheus to come to his senses and show respect for the god. But the arrogant Pentheus went out of his way to treat Dionysos like a criminal. The consequences of such impiety were deadly.

Agave, sister of Semele and mother of Pentheus, was among the Maenads / Bacchants who worshipped the wine god Dionysos. Their frenzies were ecstatic and beyond reason. In their madness, they dismembered Pentheus. The Athenian tragic poet Euripides immortalized this Dionysian drama in his play Bacchae.

It’s this fascinating and utterly tragic mythology that captivated Hellas and, to this day, attracts scholars in decoding both the myth and history of Thebes.

Reviving Thebes

One of the most successful scholars to grasp the importance of Thebes for Hellenic and Western civilization is Paul Cartledge, A. G. Leventis professor emeritus and now Senior Research Fellow at Clare College, Cambridge University. His book, Thebes: The Forgotten City of Ancient Greece (Abrams Press, 2020) does revive Thebes.

“My goal,” he says, “is to bring the ancient city of Thebes vividly back to life.” He almost does that with meticulous research of mythical, literary, historical, and archaeological sources. The result is a thorough, lively, timely, and important story of the Thebes of myth and history. Read his book.

Thebes, Cartledge says, is not a footnote but “central to our understanding of the ancient Greeks’ multiple achievements” in politics, culture and civilization affecting Western Europe, America, and the world. Thebes, he says, is alive today “as a city of the imagination… the city of Myth.”