Sixty million years ago a chunk of granite located near Los Angeles began moving northwards. Propelled by the energy of earthquakes over eons, Point Reyes slid hundreds of miles along the San Andreas fault at the divide between two colliding tectonic plates.

During the last Ice Age, 30,000 years ago, much of the Earth’s waters were locked up in glaciers, and the Pacific Ocean was 400 feet lower than it is today. “The Farallon Islands were then rugged hills rising above a broad, gently sloping plain with a rocky coastline lying to the west,” according to California Prehistory—Colonization, Culture, and Complexity.

Humans migrated from Asia walking the coastal plains toward Tierra del Fuego. Then, 12,000 years ago, the climate warmed and glaciers melted. Seas rose, submerging the plains. A wave of immigrants flowed south from Asia over thawed land bridges. Their subsequent generations explored and civilized the Americas, coalescing into nations, including in West Marin and Point Reyes.

Novelist and scholar Greg Sarris is the tribal chair of the Federated Indians of the Graton Rancheria. The tribe’s ancestors are known as Southern Poma and Coast Miwok. In The Once and Future Forest, Sarris tells the story of how the first people came to be in Marin and Sonoma counties. “Coyote created the world from the top of Sonoma Mountain with the assistance of his nephew, Chicken Hawk. At that time, all of the animals and birds and plants and trees were people. … The landscape was our sacred text and we listened to what it told us. Everywhere you looked there were stories. … Everything, even a mere pebble, was thought to have power … Cutting down a tree was a violent act. … An elder prophesied that one day white people would come to us to ‘learn our ways in order to save the earth and all living things. … You young people must not forget the things us old ones is telling you.’”

It is 2020. California is burning, beset by plague, violence and cultural dysphoria. It’s way past time to start listening to lessons encoded in the land. But can we still hear?

If so, Point Reyes has a story to tell us.

Ecological Turning Point

The North Bay community is divided by conflicted views on whether commercial dairy and cattle ranching should continue at Point Reyes National Seashore. This reporter has hiked the varied terrains of the 71,000-acre park for decades. Initially, I had no opinion on the ranching issue. Then, I studied historical and eco-biologic books and science journals. I read government records, including the Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) on Point Reyes released by the National Park Service in September. The 250-page report concludes that the ranching industry covering one third of the park should be expanded and protected for economic and cultural reasons. This, despite acknowledging that the park ranches are sources of climate-heating greenhouse gases, water pollution, species extinctions and soil degradation.

The Bohemian/Pacific Sun investigation reveals that the EIS is deeply flawed scientifically, culturally and ethically. It is politicized.

Since 2013, Sen. Dianne Feinstein and Rep. Jared Huffman have pressured the Park Service to prioritize the preservation of private ranching profits over environmental concerns. In 2017, the Park Service hired a contractor with a record of defrauding the federal government to produce the EIS. The study is structured to support the Park Service’s prior commitment to expanding commercial ranching, retailing and hoteling at the expense of endemic wildlife and plant life and regional water safety. It ignores the cumulative impacts of climate change. It minimizes and ignores the benefits of eliminating greenhouse gas- and pollution-producing ranching and transforming the park into a carbon sink.

The EIS’s privatization plan is also wildly unpopular. Members of the public and environmental organizations submitted 7,627 comments on the EIS, many of them factually detailed and consequential. The Park Service has not published an analysis of the comments. But, a statistically robust analysis by the Resource Renewal Institute determined that 91 percent of the comments called for eliminating ranching and restoring degraded lands.

The Park Service disregards these public concerns. It greenlights the further ecological destruction of Point Reyes National Seashore. Lawsuits will most likely be filed by environmental groups to challenge that action; the Park Service may not prevail.

How did we arrive at this juncture?

The Weight of Water

It’s a blue-sky Saturday, I’m hiking the bluffs of Tomales Point at the northern tip of Point Reyes. It’s hot and drought-dry. The hard-packed trail edges a fenced preserve for the world’s few remaining tule elk, a federally protected species. Small bands of the creatures chew near the trail. Sloe-eyed, meditative, they trade curious looks with socially-bubbled hikers crowding the trail, pixelating the elk with phone snaps.

Five years ago, several hundred tule elk perished of thirst during a drought that dried up the seeps inside this enclosure, according to the Park Service. But the Park Service did not come to the aid of dying elk then, nor will it now. The only water in sight is bottled and Camel-backed. There is a wire barrier between the thirsty elk and the park’s many ponds and streams, which are reserved for use by about 6,000 privately-owned cows.

There are smaller herds of tule elk in other areas of the Point Reyes. These free-rangers are the bane of ranchers. They drink water and eat grass that would otherwise fatten cattle. The Park Service favors controlling elk-herd size with bullets, but it needs permission from an EIS to justify draconian culling. Fortunately for the tule elk, people all over the world adore them. The national media publishes stories about their plight. Protesters demonstrate to free them. Kayakers deliver jugs of water to them.

Elk-worshipping aside, it is the nature of the terrains divided by the fence that illuminate the most pressing ecological issues at stake. On the elk side, native grasses and deeply rooted ground covers grow thickly, harboring birds, lizards and small mammals. This wild and perennially green foliage builds the planet’s carbon storage capacity, pulling globally heating carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere, emitting oxygen and slowing the rate of climate doom.

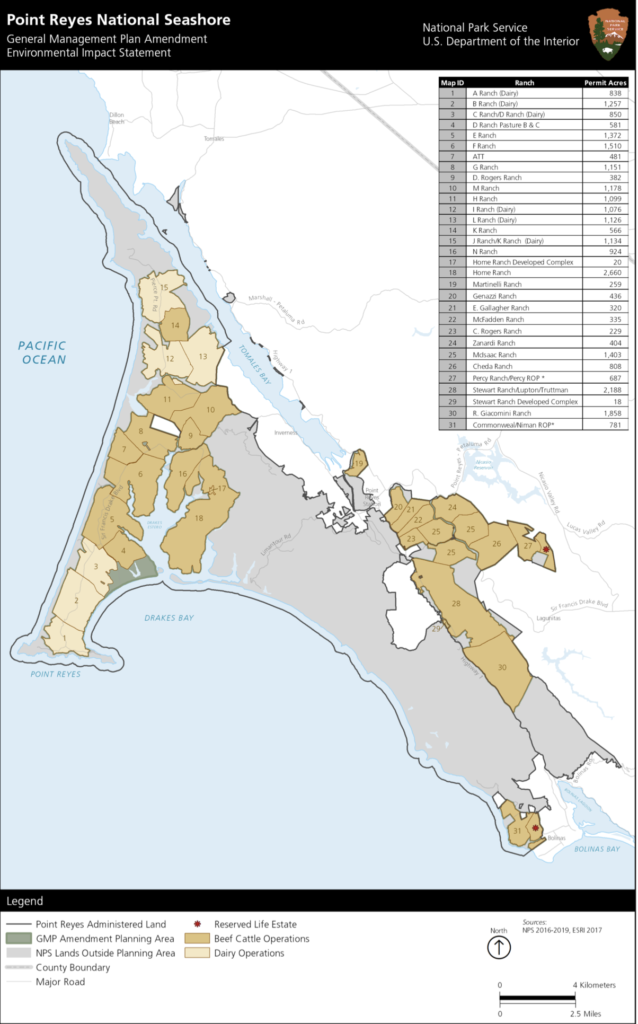

A National Park Service map shows the boundaries of the 31 existing dairies and cattle ranches in the Point Reyes National Seashore.

On the cow side of the fence, the land is barren, churned into a gray dust by hooves and crusted with methane- and nitrogen-emitting manure. When first emitted, methane is 80 times worse than carbon dioxide as a global warmer. According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, “The manure from a dairy milking 200 cows produces as much nitrogen as is in the sewage from a community of 5,000-10,000 people.” The cow herds at Point Reyes annually excrete 130 million pounds of nitrogen-laced manure into pastures, ponds, streams and loafing barns, according to USDA statistical methods. Park Service studies show that this decomposing waste releases harmful chemical elements into the park’s streams, ponds, wetlands, estuaries, Tomales Bay and the Pacific Ocean. Polluted ground waters carry loads of nitrogen, ammonia, phosphates, phosphorus and fecal bacteria. Aquatic and plant life of estuaries is choked to death by oxygen-depleting algae, by opportunistic lily plants feasting on excess nitrogen.

The EIS acknowledges that removing the pollution produced by the ranches would save federally protected or threatened species from extinction, including Coho and Chinook salmon, steelhead, red legged frogs, California freshwater shrimp, Myrtle’s silverspot butterflies and snowy plovers. Local species of insects, birds and plants would thrive in the absence of commercial ranching. As would globe-trotting flocks of birds that shelter at the seashore.

During the winter wet season, the ranchers sow muddy, lifeless pastures with shallow-rooted, non-native grasses grown as silage to feed calving cattle in the spring. Tanker trucks pump liquified manure seething with nitrogen and E. coli out of holding ponds and spray it as fertilizer on the cow food. Mainlining the nitrogen, invasive thistles swoop into the fields. Rare native plants, such as the coastal marsh milkvetch and the checkerbloom, lose the struggle for existence.

A 2013 study by U.S. Department of Interior scientists determined that California’s highest reported E. coli levels occurred in wetlands and creeks draining Point Reyes cattle ranches near Kehoe Beach, Drake’s Bay, Abbotts Lagoon and Tomales Bay. E. coli is an animal-waste bacteria that can be lethal to humans. Notwithstanding, the directors of the California Regional Water Quality Control Board regularly grant Point Reyes ranchers waivers from complying with water safety regulations that limit discharges of fecal matter and pesticides. In the EIS comments, the board’s lead scientist criticized the EIS for failing to advocate realistic remedies for curing the expected increases in toxic discharges from extending ranching operations. But the politically-appointed directors proceeded to “strongly” support the expansion of cattle ranching, telegraphing that the board will continue to waive pollution problems. And those problems are guaranteed to increase.

Ranchers regularly bulldoze tons of manure gathered from loafing barns into holding ponds called lagoons. The rotting, liquifying pools puff methane into the atmosphere. According to a 2010 Park Service climate study, Point Reyes–based cows belch thousands of tons of the poison gas into the atmosphere. Studies claim that one billion cows pose a clear and present danger to the continuance of oxygenated life on Earth. While eliminating the gases produced by commercial herds in the seashore park is not going to cure the global problem, we must start somewhere. It makes sense to tackle the issue on public lands that are supposedly dedicated to conserving natural resources. But, since 2012, the Park Service is on record as intending to expand ranching at Point Reyes no matter what scientists and the public say. That regressive attitude was not always so.

The Miwok Way

In 2009, the Park Service published an environmental history of the Tomales Bay region by historian Christy Avery. It relates how the Miwok nation scientifically tended the natural environment for thousands of years. By contrast, the EIS liquidates Miwok history, choosing instead to idealize a few hundred European settlers who immigrated to the region after the 1850s. Those tenant farmers and their three-legged milking stools, elk-tallow candles and 19th century social practices ruined the native ecology of the seashore lands with overgrazing, mono-cropping and 150 years of agricultural pollution. Oddly, the Park Service prioritizes conserving the “farming culture” of the “founding families,” whose descendants are still ranching in the park using thoroughly modern technologies.

In a more harshly historical view, the Irish, Croatian and Italian immigrant farmers were squatters on Indian land stolen centuries before by Spanish priests and Mexican militarists and eventually deeded over to a firm of San Francisco lawyers.

According to Avery, “The Coast Miwok were a semisedentary people who … depended on the fish, wild plants, and waterfowl of the estuary [and used fire and pruning and seeding] to manage and modify the land surrounding the bay.” On Tomales Bay, the Miwok families lived in villages protected by coves near freshwater streams. They “netted eel, sturgeon, flounder, perch, and herring … from rafts and boats made with tule reeds.” They fished for smelt, dove for abalone and hunted wild fowl. Seasonally, the Miwok “set fires to suppress disease and pest. … Fire turned older and dead plants into organic materials that fertilized the soil, and encouraged the growth of plants and grasses whose seeds were made into pinole, a staple, flour.” Point Reyes was a carbon sink of interdependent animal, plant and human life.

Sarris was told by elders that such was the abundance of the land and sea that the Miwok’s working day left time for making medicine and singing and dreaming about the spirit worlds and weaving the baskets for which the Miwok culture is world-renowned. “Often a person never traveled more than 30 miles from their home place during a lifetime,” Sarris told me. “If you lived on the coast, you might go as far inland as Lake County to trade for obsidian. But most people stayed in place, cultivating a mutually beneficial relationship with the landscape. Our ancestors knew the animals, they knew the trees. They pruned the oaks and burned to kill acorn-eating worms. They did not question their responsibility to keep the waters clean and free-running.” Miwoks shaped the present to preserve the future of life. “Most tribes had legends that vividly told of the consequences that would befall humans if they took nature for granted or violated natural laws,” writes M. Kat Anderson in Tending the Wild, an ecological account of how California’s first peoples engineered their surroundings.

The Rancher Way

The Europeans did not learn from the ways of the Miwok. They overgrazed lush pastures on the fog-watered coastal ranges. They did not systematically burn land, nor prune it. They killed vastly more game than they needed for sustenance. The tap-rooted grasses went extinct, replaced by stubby-rooted silage, imported ryes, oats and alfalfa that require annual re-seeding. The ranchers dammed the waters. They sprayed chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Thistle, wild oats and mustard displaced plants that had co-evolved with animals. Elk, wolves, lions, bears and, yes, humans were hunted toward extinction. Cattle churned fields of moss and grass into infertile slurry. Concrete scabbed the land. It is this exploitative version of Point Reyes’ ecological and cultural history that the Park Service intends to preserve, promoting the worst sort of profit-driven environmental depredations.

In the 1850s, dairy and meat ranches owned by the law firm Shafter & Howard exported products to San Francisco and beyond. Chinese and Indian laborers did the heavy lifting. The bodies of non-white men, women and children were violated by Europeans, both sexually and as sources of cheap labor. Overgrazing caused catastrophic flooding, eroding the peninsula. The silting of Tomales Bay from agricultural run-off destroyed the habitats of sea creatures. Entrepreneurs constructed railroads on top of bayside levees, reconfiguring ecologies. (A few Miwok families held onto bay lands such as Laird’s Landing; lands that incubated the revival of the tribe in the 1990s, when the Miwok and Pomo people succeeded—against great odds—in reclaiming their sovereignty.)

As dairying expanded throughout California at the turn of the 20th century, milk and cheese prices plummeted. The lawyers sold their Point Reyes farms to tenants. Investors developed a tourist trade. Newly constructed residences, hotels and restaurants spewed raw sewage into a Tomales Bay slick with oil spilled from boats. Dairy-industry effluvia killed fish and stank. Point Reyes became hellish.

Starting in the 1960s, environmentally-minded Marin residents had had enough. They passed zoning and environmental laws to stifle further commercial development of the county’s rural areas. Congress legislated Point Reyes as a national park, “protected” from further environmental degradation. During the 1970s, the feds paid the park’s ranching families a fair market value of $57 million ($382 million in today’s dollars) for their properties. Most of the ranchers signed below-market value leases and agreed to vacate in 25 years. The bold idea was to phase out ranching and allow native flora and fauna to regenerate; the park’s undeveloped beaches were set aside for recreational picnics, swimming and fishing.

But instead of leaving by the millennium, the ranchers formed the Point Reyes Seashore Ranchers Association. The group has lobbied Feinstein, Huffman and the Park Service to keep the cheap rents in perpetuity; to expand livestock and agriculture operations; to run bed and breakfasts and retail stores on the ranches; and to “extirpate” the park’s free-ranging Tule elk, effectively signing their death sentence. Environmentalists fought back with lawsuits.

Promises, Promises, Politics

In 2012, Obama’s Secretary of the Interior, Kenneth Salazar, a cattle rancher, intervened in the dispute over commercializing the park and cut the baby in half. He ordered the removal of a rancher-owned oyster farming and retail operation from Drakes Estero because it “violated the policies of the National Park Service concerning commercial use” and its removal “would result in long-term beneficial impacts to the estero’s natural environment.” Then, Salazar directed the Park Service to “pursue” the possibility of offering the ranchers 20-year commercial leases in accord with applicable laws. Salazar’s direction was not a law, nor a regulation, nor an order binding upon future governance. Nor could the leases be legally extended without first assessing the environmental consequences; although, at the urging of two members of Congress, the Park Service pursued extending the leases without first doing an EIS.

In 2013, newly elected congressman Jared Huffman lobbied the Park Service to extend the leases. Although he calls himself a “progressive” and an “environmentalist,” Huffman accepts major campaign donations from the dairying, logging, sugaring, real estate and weapons industries. (See “Where Jared Huffman Gets His Campaign Money” below.)

In 2014, Feinstein, who also accepts donations from agribusiness, urged Salazar’s successor, Sally Jewell, to “renew the leases for at least twenty years as Secretary Salazar promised.” Feinstein did not mention the many promises the federal government has broken with the Coast Miwok.

Derailing the politically-powered rush to renew the leases without an environmental review, the Resource Renewal Institute, Center for Biological Diversity and Western Watershed Project won a federal court order in 2016. The court required the Park Service to produce an EIS laying out the environmental pros and cons of continuing commercial ranching versus requiring the ranchers to vacate as they had promised.

Then, undoing a century of environmental protections, the Trump regime moved to massively privatize parks and forest service lands for exploitation by logging, mining, energy and cattle industries. In 2018, Huffman attempted an end-run around the EIS process. He authored a House bill ordering the Park Service to sign perpetually renewable 20-year leases. The bill passed with enthusiastic support from anti-environmental regulation Republicans, but died in a Senate committee.

Since 2012 there has never been any doubt about the outcome preferred by the Park Service—the granting of ranching leases in perpetuity. But the EIS was not principally researched and written by Park Service employees. The $559,000 job was contracted to Louis Berger Group, Inc. despite the engineering firm’s shadowed past. In 2010, Louis Berger Group paid $69 million in civil and criminal fines for defrauding the federal government in war-zone contracts in Iraq and Afghanistan. Adding to its ethically troubled record in 2015, the firm paid “a $17 million criminal penalty [for] bribing foreign officials [to] secure government construction management contracts,” in India, Indonesia, Vietnam and Kuwait, according to the U.S. Department of Justice. The World Bank debarred the firm “for engaging in corrupt practices.”

The Park Service hired the Louis Berger Group in 2017, despite wide reporting of the group’s transgressions by the media, and despite the existence of any number of environmental firms able to conduct an impartial, scientific investigation.

Attorney Dinah Bear has served the White House through successive administrations as an expert on the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) which governs the EIS process. In a telephone interview, Bear excoriated the practice of outsourcing an EIS to consultants who are easily incentivized to deliver results desired by political decision makers. “Trump has eviscerated the scientific legitimacy of the EIS process,” Bear said. For example, an EIS is no longer required to examine the long-term impacts of climate change. Regardless, said Bear, “The courts are inclined to invalidate an EIS if it ignores the cumulative impacts of climate change.”

Climate Change?

The EIS barely mentions climate change, except to dismiss it as a serious threat. Despite ample scientific research demonstrating that Point Reyes’ ecological health is and will continue to be distressed by extreme heat, rising seas and dramatic shifts in weather patterns, the EIS claims the impacts of climate change are “difficult to predict,” and in any case the effects will be negligible, because “all ranches in the planning area are at an elevation where sea-level rise would not have a direct impact.”

Contradicting the benign climate future postulated in the EIS, the California Coastal Commission predicts regional sea levels to rise catastrophically, as much as 12 inches by 2030, and up to 66 inches by 2100. In the short term, “Beaches, estuaries, marshes, wetlands, and intertidal areas on the Marin Coast … will experience inundation, erosion, and the potential for complete loss.” The stability of water, septic and sewage pipelines serving Point Reyes are threatened. Entire species of animal and vegetative life could be extinguished. Expected flooding from heavier rains will worsen erosion and increase ground pollution from agricultural activities throughout the park and along Tomales Bay. While ocean waves are not likely to roll over bluff-top ranches, that does not mean that climate-induced catastrophes will not vastly worsen the peninsula’s already-untenable ecological situation.

According to Avery’s environmental history, “Dairy waste management became one of the most problematic issues for ranchers in the late twentieth century. Dairy farmers had typically sought properties with creeks that would provide water for their stock, but these same creeks carried animal wastes into the bay. When manure washed into the estuary, the high levels of ammonia in the waste poisoned fish and posed threats to human health. In rainy weather, sewage ponds overflowed, and waste material washed into the nearby waterways. The 10,254 dairy cows and beef cattle in the watershed produced 1,066,574 pounds of manure per day in 2000. Cattle also increased erosion as they trampled streambanks, causing [48,000 tons of] silt to wash into the bay [every year].

“By the late twentieth century, Tomales Bay exceeded federal limits on fecal coliform more than ninety days each year. … In addition to dairy wastes and human sewage, the waters of Tomales Bay have also had to absorb excessive amounts of mercury—one of the most toxic metals.” Mercury mined at the Gambonini ranch was sold to manufacture dental fillings, thermometers, and fluorescent lights.

The good news, according to Avery, is that the bay can be regenerated by “restoring wetlands and wildlife populations [and eliminating] unwanted outcomes of human activities.” Avery praises the Park Service’s restoration of a wetland on the decommissioned Giacomini Ranch at the head of Tomales Bay as an example of responsible land management and of human agency allowing the land to heal.

Greenhouse Gas Doom

The EIS acknowledges ranching will “continue to emit pollutants and greenhouse gases associated with cattle grazing, manure management on dairies [and] combined with the impacts from past, present, and reasonably foreseeable actions, the total cumulative impact on air quality would be adverse.” In dire fact, methane generated by dairying and cattle ranching contributes at least 30 percent of the globe’s greenhouse gas load.

Investigative reporter Christopher Ketcham’s This Land: How Cowboys, Capitalism, and Corruption are Ruining the American West notes, “In 1991, the United Nations reported that 85 percent of Western rangeland was degraded with overgrazing … the impact of countless hooves and mouths over the years has done more to alter the vegetation and land forms of the West than all of the water projects, strip mines, power plants, freeways, and subdivision developments combined.” That statement is worth pondering.

Influential groups such as the Marin Agricultural Land Trust (MALT) and Marin Conservation League pride themselves on stopping strip mall-type development in rural areas. But their advocacy of ecological damaging commercial ranching development on private and public lands is a sign of cognitive dissonance—believing what you prefer to believe even when the facts rebut.

For instance, the belief that eating grass fed beef is a “sustainable” practice is a misnomer when it comes to stopping global warming. Multiple studies show pasture-bred cattle emit substantially more methane than penned-up, grain-fed cattle who move about and burp less. Transitioning consumers to buying only grass-fed beef products would require increasing the national cattle herd by 30 percent, nearly doubling the amount of methane emissions and greatly exacerbating the stresses of global heating, according to a 2018 study by the Animal Law and Public Policy Program at Harvard Law School.

There are huge economic benefits to keeping our public lands cow-free, Ketcham explains: “Photosynthesis and biomass production, carbon sequestration, climate regulation, clean air, water retentions and filtration, fresh water, soil retention, nutrient cycling, pollination—all [are] products of public lands” valued in trillions of dollars, worldwide.

The relatively small portion of the EIS devoted to Alternative F, the option to remove commercial ranching from the park, acknowledges that eliminating ranching would “end ranching-related emissions,” including methane, carbon dioxide, nitrogen, and ammonia, four of the main drivers of global heating. The EIS notes that Point Reyes ranches account for 22 percent of the greenhouse gases generated by agricultural activities in Marin County. Eliminating dairy and cattle ranching in the park would significantly reduce its contribution to the hockey-stick curve of global heating. Dodging that inconvenient fact, the EIS suggests ranchers could combat global heating by “voluntarily” practicing carbon farming.

While carbon farming is an effective way of slowing global heating, the EIS does not lay out a plan for implementing the practice. In fact, quite the contrary.

The Ins and Outs of Carbon Farming

In October, Science published a plan to conserve one-third of the world’s potential farmlands as wildlife havens and carbon sinks, without diminishing the food supply. The Global Safety Net is a blueprint for sucking carbon out of the atmosphere and trapping it in non-agricultural vegetation. It would reverse the rate of global heating. It makes an empirically grounded case for returning nutrient-depleted, over-grazed public lands to carbon-storing native plantings. The scientists acknowledge, “The tools and designations will vary by place and must be locally appropriate. … to be politically achievable [the plan] requires broad engagement from civil society, public agencies, communities and indigenous peoples.”

Half of California’s land area is grassy rangeland, much of it overgrazed or farmed without regard for carbon sequestration. Restoring Point Reyes National Seashore is a logical place to start the healing. The EIS references a local non-profit called the Marin Carbon Project as its carbon-farming expert. That organization is not calling for reducing or eliminating cattle ranching. Rather, it calls for spreading manure-based “compost” on silage crops; the solid compost emits methane and nitrogen, just less of it than liquid waste. Looking for a technological fix, the Marin Carbon Project calls for installing methane digesting machines on top of lagoons of putrefying poop. The suggestion is that if the ranchers buy barn-sized digesters for construction on top of the holding ponds, then the explosive hydrocarbon can be usefully transformed into electricity. Digesters of this type cost $1.5 to $5 million dollars apiece, plus tens of thousands of dollars a year to operate, and require cow herds numbering in the thousands to be cost effective. Why not just get rid of the methane’s source—the cows?

Dr. Jeffrey Creque directs the Marin Carbon Project. He farmed in the seashore for decades and favors extending the leases at Point Reyes. Creque wrote, controversially, in Point Reyes Light that “methane from ruminants, whether cattle or elk, is essentially, irrelevant in the global warming equation.” In an interview, Creque said he had meant that carbon dioxide is more dangerous than methane in the long run. He agreed that methane heats up the atmosphere faster. Methane eventually morphs into carbon dioxide, adding to the long-term greenhouse gas load. Creque then argued that we have to keep the thousands of cows on Point Reyes because the ranches are vital to the local economy.

Local Economics

The ranches support 64 full-time jobs—out of 124,700 jobs in Marin County—and generate $16 million in annual revenue. By contrast, park-related tourism revenue dwarfs this agricultural output. According to the EIS, “In 2018, visitor spending [in the park] supported 1,150 jobs in the local area and had an aggregate benefit to the local economy of $134 million.” Visitors do not come to Point Reyes to watch cows. And the park’s contribution to the $260 million regional dairying and cattle raising economy is fractional.

The ranching businesses are also an economic burden on taxpayers. Public records reveal that ranch rents are fifty percent below market; the Park Service spends $500,000 a year on ranch maintenance and capital improvements; the ranchers have received $2.2 million in federal farming subsidies since 1995. Without receiving millions of dollars in government handouts, the Park Service argues, these ranchers would likely go out of business. Or not.

Many of the Point Reyes–based ranching clans operate cattle and dairy spreads outside the park in West Marin which are capitalized by tens of millions of dollars in conservation easements (“Malted Millions,” Sept. 30).” While the loss of the seashore-based ranches might negatively impact some private profit margins, the effect to the regional and state economies would be negligible. Contrast that to the social, economic, ecological and educational gains to be made from allowing the Miwok lands to regenerate as carbon sinks that are of incalculable value to life in this age of burning ecosystems. If we cannot save our once-vibrant seashore park from further ecological destruction, how can we save ourselves and our planet?

Weaving the Future

Sarris tells me a story:

“It was around 1988 and I was driving up the coast with Mabel McKay, the last of the medicine dreamers. And she looked out the window of the car. And she said, ‘This is my dream. It’s all going to burn. Everything’s going to go dry. And there’s no stopping it. The ocean is going to get warm. Everything’s going to burn and go dry.’

“And I was a younger man, and I excitedly said, ‘Oh, Mabel, what do I do? What do I do?’

“And she started laughing. And she said, mocking me, ‘That’s cute. What do I do? What do I do? How cute.’

“And I said, ‘No, seriously, what do I do?’

“And she took a silent beat. And she turned to me and she said, ‘You live the best way you know how, what else? The earth will be replanted, it will be replanted. There will be people here. But we don’t know who they’re going to be.’”

Where Jared Huffman Gets His Campaign Money

Northern California Rep. Jared Huffman is on record as supporting legislative acts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Which is why his 2018 bill to protect the expansion of cattle ranching at Point Reyes surprised his environmentally minded supporters. Data provided by OpenSecrets.org shows that during the course of Huffman’s congressional career he has accepted large sums of campaign money from corporations whose environmental and health agendas may not reflect the political wishes of his more greenish constituents.

Dairy Farmers of America ($5,000). DFA donated to Huffman’s campaign shortly after the congressman lobbied the U.S. Department of Interior in 2013 to extend cattle ranching leases at Point Reyes.

American Crystal Sugar Company ($40,000). Based in the Midwest, the United States’ top sugar manufacturer and distributor markets millions of barrels of high-fructose corn syrup to breakfast cereal brands and bags of white sugar to households. It chops sugar beets into feed for cows.

Honeywell International ($39,000). The Environmental Protection Agency lists the weapons and chemical manufacturing behemoth as one of the most toxic corporations in the United States, with more than 100 Superfund sites.

Berkshire Hathaway ($37,999). Billionaire Warren Buffet’s holding company is heavily invested in environment- and health-destroying corporations, including Barrick Gold, Coca-Cola, Apple, Bank of America and a portfolio of carbon-spewing railroads and airliners.

Green Diamond Resources ($18,384) Huffman has received regular contributions from this clearcutting logging company throughout his time in Congress, according to federal campaign finance records. In the Nov. 2020 election, Huffman was the top recipient of campaign donations from the company ($6,500), which also gave money to the anti-environmentalist, pro-fossil fuel campaigns of Sens. Susan Collins (R-Maine) and Lisa Murkowski (R-Alaska).

Huffman’s campaign portfolio of global heaters includes Sierra Pacific Industries, PG&E, Goldman Sachs, Carnival Corporation, Bechtel Group and General Motors.

Huffman commented, “I receive contributions from hundreds of groups and thousands of individuals, including far more from the environmental community than from the groups [your newspaper] portrays, and none of these donations has ever influenced my policy decisions.”

Huffman’s congressional career donations total $138,529 from environmental groups and $189,477 from agribusiness, according to Open Secrets. He gets 27 percent more money from agribusiness than from environmental interests.

This piece first appeared in the Pacific Sun.

Please support investigative reporting: www.peterbyrne.info