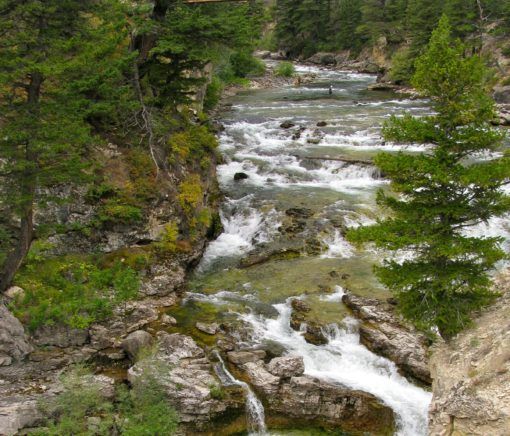

Upper Gallatin River. Photo: Jeffrey St. Clair.

In this era in which climate change and global warming occupy ever more of the public discourse and awareness, it is striking that its brethren environmental concerns, all of no less consequence, remain starkly and fatefully off the public radar screen. These threats could be enumerated to include, among others, deforestation, ocean acidification, grasslands and desert destruction, stream de-watering, wetlands subsidence, ubiquitous pollution, massive species extinctions, unendingly growing human overpopulation of the planet, and intractably continuing shrinkage of wildlands and the flora and fauna dependent upon them. When we hear of climate change or global warming, it is almost always stated as though it were our sole environmental worry, and as though the world’s biotic community would be just fine if only we solved that one problem. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. We ought to be speaking of the multi-pronged threat of environmental collapse. Environmental collapse, not sheer climate change, should be the watchword.

An eponymic, impending example of this danger lies in America’s iconic Yellowstone, home to all species known at the time of the Louisiana Purchase and the explorations of Lewis and Clark. Although the 2.2 million-acre National Park by the name of Yellowstone is what the public associates with the region’s wildlife, the people do not realize how much Yellowstone relies on the significant lower-elevation valleys of its Greater Ecosystem’s 22 million acres being protected by the Wilderness Act of 1964. Indeed, the center of the Ecosystem is roughly surrounded – with but one crucial and soon to be decided exception – by legislated Wilderness, the only administrative designation able to protect the largest and most diverse public lands in the Lower Forty-eight States, with its wolverine, lynx, bison, moose, grizzly bear, and wolves, to name a few.

The Gallatin and Madison Ranges on the northwestern tier of the Park are the only woefully unprotected part of this vast land. The region’s major conservation groups, all part of today’s NGOization of what were once noble institutions now ideologically determined and financially dependent on corporate-funded foundations, have all been lulled into becoming spokespersons for the sacrifice of crucial lands here to economic and political expediency. The Sirens’ Songs of neoliberalism’s reach are what they are. They tell us that their proposals for the land will get the job done, while studiously and effectively dodging any public and rigorous discussion of the knowledges of both science and aesthetics.

With harmless-sounding or even hope-inducing rhetoric of the creeping “collaborate and compromise” model of land-use disputes on public lands, self-selected groups have eliminated the public from not only having a voice but from even knowing what is happening. They conduct highly funded public relations campaigns designed to indicate that the land is being protected while everyone is celebratorily learning to get along. Grassroots and wildlife voices are occluded, even while the dominant groups lobby to fill people’s minds with the false sense that everything is being taken care of.

Indiscriminate logging still poses a threat here, even though often in the guise of the perversely named “restoration logging,” kind of like Trump’s idea that California needs to fight its fires by raking the forest floor. But in heartbreaking actuality, some of the most crucial lands here in The Last Best Place are imminently facing a point of no return from a new danger, hard to grasp though it is for people who don’t live here and have a history of frequenting the affected areas. The New West faces the invasion of what legendary wilderness guide Smoke Elser refers to as a new breed of recreationist, quoted here by conservation activist Mike Bader, “Mountain bikers are out to challenge the resource. It’s about how fast you can go and how many miles you can put on. Snowmobilers are after the highest mark on the hillside, the highest speed across the meadow” (Missoulian 4/23/17). Journalist Todd Wilkinson recently and aptly called it “industrial-strength outdoor recreation,” supported by “the outdoor recreation industrial complex” and its consumptive consumerism. My own recent “Return to Leopold: Dare We Speak Up for Yellowstone” links the forces concealing the rest of the story to the dynamics of NGOization as evocatively and viscerally depicted by Arundhati Roy, in her (2014) Capitalism: A Ghost Story.

Once Leopoldian land-ethically grounded groups like Montana Wilderness Association and The Wilderness Society have now, for example, released a slick promotional video that deftly makes the new industrial invasion of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, in a Ray Bradburian Fahrenheit 451 sort of way, look like Nirvana. But don’t be fooled, even if they are. In point of fact, a fact that is tempting to look away from, the New West is facing a choice between a juvenile, limitless seeking of pleasure that will rapidly abolish Yellowstone, and a transformed human ethic that aesthetically appreciates both the fragility and the sublimity of the primal lands of the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem.

If you have an aesthetic capacity, then you will understand the following Chaucerian reference.

No sword blade sent him to his death,

my bare hands stilled his heartbeats

and wrecked the bone-house.– Beowulf

Full of such spine-chilling language is the epic poem my then fifteen-year-old son and I read aloud twenty years ago, deep in Montana’s Bob Marshall Wilderness, not 200 yards from an enormous grizzly bear track we’d spotted on our way into camp. We both knew in our bones, and in the immediacy of consciousness, how our own “bone-cages” could so easily be crushed by the Beowulfian figures of nightmares, and the simultaneous specter of awe, grandeur and terror, that we call the grizzly bear. We knew how unthinkably vulnerable we were to this esteemed emblem of the wild. And we knew how alive we were! It was the kind of experience that makes a person recall quotes like psychoanalyst D. W. Winnicott’s, “Oh God! May I be alive when I die.”

We are not only rapidly environmentally denuding, crippling, and de-wilding our planet by studiously ignoring ecological science, we are anthropomorphically purging our world of a wildness that makes us human, that keeps us interdependently tied to the primal, and staves off our slide toward a malformed Homo Technicus.

The choice is ours. But only for a little while longer. And only if we have the courage to look beyond the trite sound bites of the Big Greens, and see the complex, nuanced Real that is nonetheless right before our eyes.