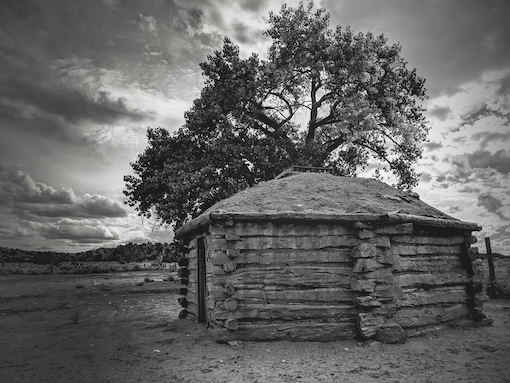

Traditional Hogan on the Navajo Reservation. Photo: Alter-Native Media.

Governor Michelle Lujan Grisham of New Mexico warned President Trump nearly a month ago that coronavirus “could wipe out tribal nations.” Governor Lujan Grisham cited “incredible spikes on the Navajo Nation,” to which Trump responded, “Boy, that’s too bad for the Navajo Nation – I’ve been hearing that.” Since then, Covid-19 deaths on the Navajo Nation have increased by over 2000% with over 1,000 tribal members testing positive, an infection rate that has almost quadrupled subsequent to Grisham’s call with Trump.

Per capita, only New York and New Jersey exceed the COVID-19 infection rate on the Navajo Nation. Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) indicates that if COVID-19 follows the same pattern as H1N1 in 2009 and the flu pandemic of 1918, the devastation throughout Indian Country will proportionately far exceed that of the rest of the US. When age-adjusted rates per 100,000 population were compared, the 2009 H1N1 influenza death rate among tribal people in the US was four times that of all other races combined.

As an ethnic minority, the continent’s first people are in the highest risk category with vulnerability to coronavirus. Tribes endure levels of poverty unimaginable to most Americans, with a life expectancy on some reservations lower than in Bangladesh and disproportionate numbers of tribal members who are immuno-compromised in communities ravaged by diabetes and other chronic “pre-existing health conditions.”

That’s part of day-to-day life for one side of my family, where my aunts, uncles, nieces and nephews are among those 600 times more likely to die from diabetes than the general population and maybe 200 times more likely to succumb to TB. They’ve fallen even further behind Bangladesh on the Northern Cheyenne Reservation in the last couple of years; if you live past 55-years old you surpass expectations. There isn’t an ICU bed to be found on the reservation in southeastern Montana.

“We actually don’t know if we have cases here because we haven’t been testing until recently,” began Theresa Small, Incident Command Coordinator for the Northern Cheyenne Tribe. “Indian Health Service (IHS) is not equipped for anything resembling this,” she said, and added “we’re doing what we can to improvise.” That includes preparing the high school to be a quarantine facility and “maybe setting up a field hospital, but that would have zero isolation units and minimal beds. We’d try sending some positive cases to a local hotel.”

The tribe has virtually no PPE but was sent one of 250 Abbot ID Now test machines the IHS designated for Indian Country. Twenty-five out of five thousand tribal members on the reservation have been tested for COVID-19, but very few more will be in the near future due to another Trump administration logistical oversight: when the two dozen or so tests supplied have been used an application for more has to be made to the International Reagent Depository. Plus, there’s already a shortage of swabs for the tests.

When over 80% of your people live below the poverty line in the best of times, that’s the definition of poor. It’s hard to stay six-feet away or isolate when twenty family members routinely live in a four-room HUD house. The homeless would love to have somewhere to shelter-in-place but don’t, so they keep asking for anything to get through one day to the next outside the Cheyenne Depot gas station. Social distancing is a luxury not accorded to the poor.

From housing shortages to overcrowding, inadequate and underfunded health care programs, through to reservation districts without electricity and running water, in the third decade of the Twenty-first Century, Indian Country still provides what Benjamin R. Brady and Howard M. Bahr described as a “perfect storm” for a pandemic in Fall 2014’s American Indian Quarterly.

Initially, the Trump Administration omitted tribal nations from the $2-trillion coronavirus stimulus package. Upon passage, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act included the $8 billion Tribal Stabilization Fund. However, instead of rapidly disbursing the funds to the highest risk areas, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt instituted a timetable of consultation sessions to set forth eligibility criteria for the disbursement of the funds. The latest was on April 9.

“We must ensure these life-saving resources quickly get to the field for Tribes, Indian Health Service facilities, and urban Indian health organizations. Tribes have been very clear that COVID-19 will be devastating for their communities if they do not get the necessary public health resources,” responded Senator Tom Udall (D-NM), Vice Chairman of the Senate Committee on Indian Affairs, who led a “bipartisan, bicameral group” of 18 US Senators and 12 US House members who urged President Trump to act expeditiously. Instead of days, we should count how many deaths and confirmed cases that was ago.

Many of the 27,000 miles of the Navajo Nation lay in Arizona. Tribal people make up fewer than 5% of the state’s population but 16% of the COVID-19 fatalities. It may currently be the epicenter of the coronavirus crisis in Indian Country, but it is not the only tribe suffering increased COVID-19 fatalities and cases. From the Cherokee Nation in Oklahoma to the Gila River Indian Community in Arizona, coronavirus is claiming lives. Governor Anthony Ortiz of the Pueblo of San Felipe has warned that the situation is “dire.” The Pueblo of Zuni and Zia Pueblo have escalating infection rates.

“We recognize that this silent killer is threatening our way of life, which is why we need all the support we can get, starting with federal dollars,” said President Jonathan Nez of the Navajo Nation. Over a month ago, Nez cautioned that with only 28 ventilators and 13 ICU beds in IHS facilities on the reservation, the tribe’s health care provision would quickly reach critical mass.

Udall revised his assessment of Trump’s response to “incompetent, slow, and utterly dysfunctional.” Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation, Chuck Hoskin, Jr., said it “feels like a robbery happening in broad daylight.” Not one dollar of the CARES Act Tribal Stabilization Fund has made it to the frontlines yet, and now, in a move Straight Outta Trumpton, millions of it likely never will. The Trump administrations Assistant Secretary for Indian Affairs, Tara Katuk Sweeney, was handpicked for the role by Trump’s previous extractive industry shill who ran the Department of Interior, Ryan Zinke. Sweeney, an Iñupiat from Utqiaġvik, Alaska, traded her million-dollar salary as vice president of the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation and two approximately $500,000 incentive programs for the highest position in government with direct responsibility to tribes.

“I am humbled by the confidence President Trump and Secretary Zinke have shown in me,” Sweeney said upon her nomination in October 2017. True to Trumpton, she retained her “inherited financial interest” in the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation, the most financially successful of the 13 Alaska Native Regional Corporations that were established pursuant to the 1971 Alaska Native Claims Settlement. All are for profit corporations with extractive industry portfolios. During Sweeney’s final year as VP, the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation posted $3 billion from fossil-fuels.

With the opening of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge and the cultural devastation that will befall the Gwich’in, the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation should be able to increase those “inherited financial interests” as it holds the subsurface rights to some 92,000 acres of the pristine ecosystem that is on the block to be plundered, the “1002 Area” to Sweeney, what the Gwich’in call “The Sacred Place Where Life Begins.”

Trump’s Let Them Eat Cake Act of 2017, the so-called Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, included a rider to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to extractive industry, long a Republican craving. One of Sweeney’s last acts as an Arctic Slope Regional Corporation executive was to be photographed standing behind Trump in the Oval Office surrounded by her colleagues and a handful of community members. Senator Lisa Murkowski (R-AK) looks almost as smug as Sweeney in the photo. Murkowski was responsible for adding the rider to open the Refuge to drilling, and in a speech on the Senate floor to celebrate the abysmal maneuver crowed, “When I start to name names, I think of Tara Sweeney.” And back in Whitefish, Montana, Ryan Zinke knocks back one of his own dubious microbrews content that on its own his pick of Sweeney merited his self-styled flag to be flown over the Department of Interior while he dismantled the agency with a troglodysence becoming of the Dear Leader himself.

Now, contrary to the intent of the CARES Act, Sweeney is about to oversee the disbursement of funds to Alaska Native Corporations that were appropriated to aid the 574 federally recognized Indian tribes, some of whom exist in Third World socio-economic bondage and will need every dollar to survive the pandemic.

On April 14, the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association, representing sixteen tribal nations in South Dakota, North Dakota and Nebraska, wrote to Bernhardt and Treasury Secretary Mnuchin to call for Sweeney’s removal.

“Charged with a large public trust, she unfairly sought to divert emergency Tribal Government resources to state-chartered, for-profit corporations owned by Alaska Native shareholders, including her and her family. Further, she seeks to deny the very existence of Indian country,” the six-page letter begins.

The Global Indigenous Council furnished the letter to House Natural Resources Committee Chairman, Congressman Raul Grijalva (D-AZ), Vice Chair, Congresswoman Deb Haaland (D-NM), and Chair of the Subcommittee on the Indigenous Peoples of the US, Congressman Ruben Gallego (D-AZ). The three then joined a bipartisan letter to Mnuchin and Bernhardt with nine other members, led by Congresswoman Betty McCollum (D-MN) with a straight-forward message, “the spirit and language of the law is clear” and “we echo the opposition expressed by many of these federally recognized tribes to the inclusion of Alaska Native Corporations as eligible entities under the CRF.” To do so, warned the lawmakers, “would clearly be contrary to congressional intent.”

Every major inter-tribal organization in the contiguous US then joined a letter that echoed the House members, which detailed how Sweeney had contradicted her testimony at her confirmation hearing by advancing the interests of Alaska Native Corporations, and highlighted that if not reversed, what the Great Plains Tribal Chairmen’s Association called Sweeney’s “money grab” would have grave implications for the federal-Indian trust responsibility. According to Bernhardt, possibly the only appointee who could have made Zinke appear honorable and Scott Pruitt environmentally conscious, Sweeney is “dutifully following the law set forth in the CARES Act.” On April 17, six tribes filed suit against the Trump administration over the issue.

Senator Udall also gave it a try, and again attempted to explain to Bernhardt the criteria of the CARES Act. “Title V of the CARES Act limits eligibility for the tribal portion of the CRF specifically to Tribal governments to ensure parity between states, territories, and tribes,” he wrote, presumably in capital letters and resisting the temptation to use joined-up writing. He also exposed the sham nature of Bernhardt’s consultation process. “Consultation can only truly be meaningful when a Department reflects the Tribal views received in its policy making” and concluded that Interior had once again “failed.”

Boy, that’s too bad for the Navajo Nation, eh Donald? Maybe you could send a couple vials of hydroxychloroquine? President Jonathan Nez and Vice President Myron Lizer are now in self-quarantine after exposure to COVID-19, and the death toll on the reservation rose again at the time of writing. 16,000 homes on the Navajo Nation alone don’t have running water, so how do these people keep washing their hands? “People can’t afford to be washing their hands so often with soapy water, they’re using it for drinking water and for their livestock,” said Nez at a recent virtual roundtable hosted by Congressman Grijalva.

Without readily available, time-efficient and effective testing, Indian Country’s fight as a whole against COVID-19 will resemble the desperate struggle being waged on the Navajo Nation. President Julian Bear Runner reported that the Oglala Sioux Tribe has only 24 COVID-19 test kits for over 20,000 residents on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Lockdowns, curfews, and roadblocks may mitigate but aren’t stopping the virus being carried into vulnerable tribal communities. The coronavirus has reached Pine Ridge and Standing Rock. With the Smithfield Foods pork plant outbreak in Sioux Falls, the chances of the other Great Sioux Nation reservations in the state escaping diminish with every newly confirmed case.

Governor Kristi Noem claims that no stay-at-home executive order she could have signed would have prevented the pork processing plant from becoming one of the largest recorded COVID-19 clusters in the country. Despite a surge of cases across South Dakota in April, Noem continues to approach the crisis like a living Ayn Rand experiment, except not everybody’s living now and everyday at the coronavirus briefing in the White House we are exposed to Rand’s concept of “ethical egoism” when Trump holds court.

It’s about a forty-minute drive from the Smithfield plant to the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe. Two hours to the Yankton Sioux Tribe. Just over two to the Crow Creek Sioux Tribe. Four to the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe. Around five to Pine Ridge. The latter three are in Buffalo, Ziebach and Oglala Lakota County respectively, some of the most impoverished counties in the US. “Our health care system can handle what’s coming at us,” Noem said on April 16. But what about the IHS? The chronically underfunded, forlorn agency has 71 ventilators and 33 ICU beds available nationwide – how many does Noem think are available in the four small IHS hospitals in South Dakota?

“We’ve seen reports of climbing infections and death tolls among the Navajo Nation and fears about the disproportionate impact the virus could have on Indian Country. It’s unconscionable, and it shouldn’t be the case in the United States of America in the 21st century. But we know exactly why it is: Black, Latino, and Native Americans are still less likely to have health insurance. Less likely to have access to health care. More likely to have underlying conditions, like asthma and diabetes, that make them more vulnerable to this virus. And, more likely to face exposure to air pollutants that may be associated with higher COVID-19 death rates.”

Right on. Right? A politician issuing a statement on COVID-19 and focusing on “the racial inequities of COVID-19” and how the federal government’s reaction has amplified “the structural racism that is built into so much of our daily lives, our institutions, our laws, and our communities.” Wait now. It’s Vice President Joe Biden who recently said that and concluded with how leaders in government needed to do “the necessary work to rip out the structural racism that creates these inequalities wherever we find it.”

Yeah, that Joe Biden. Wall Street Joe. Sell-out Joe. As bad as Hillary, Joe. Doctrine of Discovery apologist Joe, who has committed to the most substantive policy proposals to make inroads into the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women crisis. Racist Joe, who the first black president picked as his running mate. Serial sexual abuser Joe, whose signature legislative achievement is the Violence Against Women Act. Senile Joe, who must have developed dementia in the last month or so because there was no sign of it when I last visited with him, whereas the current occupant of the White House indisputably demonstrates deteriorating incontinence of the brain and diarrhea of the mouth. Not much better than Trump, Joe. Please. Where the fuck have you been since January 20, 2017?

There’s a time and a place to address this horseshittery, but in the context of COVID-19 devastating Indian Country, ask yourself this: do you think a Secretary of the Interior Raul Grijalva would have acted differently to Bernhardt? Do you think we’d have Tara Sweeney? Do you think tribes would have to be applying for these federal funds through grant applications as if the pandemic wasn’t happening? And while you’re at it, think in general terms about the Trump-Zinke-Bernhardt catastrophe at Interior – every abuse of the federal-Indian trust responsibility, every act of environmental destruction, every violation of the ESA, every giveaway to extractive industry. Had Hillary won, Grijalva was reputedly on the shortlist for the job. If Biden wins, he’s likely to be on a shorter list.

Take heed, at this moment in 2020 we are all like those folks begging outside the Cheyenne Depot to make it through until tomorrow. Remember that in November. Your freedom to be the wokest of the woke amongst the liberal intelligentsia could depend upon it.

Rain is the director of the trending documentary Somebody’s Daughter which focuses on the Murdered and Missing Indigenous Women (MMIW) crisis. One review describes the film as “among the most important documentaries made on not only MMIW, but also on Indian Country in the twenty-first century.” His previous film, Not In Our Name, had the distinction of being entered into the Congressional record at a House Natural Resources Committee hearing in May 2019. Rain is a member of the Strange Owl family from Birney and Lame Deer, Montana. He is also Romani and is often listed among “notable Romani people.”