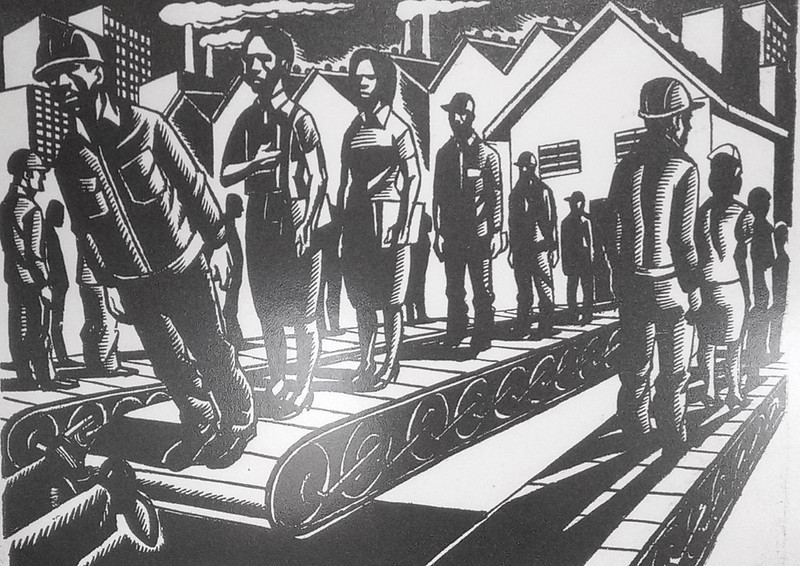

Leonilo “Neil” Dolirocon’s socialist art at National Gallery Manila. Photograph by Kandukuru Nagarjun – CC BY 2.0

It takes a virus to strip away the veneers, focus everyone’s attention, and reveal capitalism in all its repulsiveness. It’s shown that, in these times of COVID-19, millions of people are worrying about how to survive as the flimsy structure of finance finagling, otherwise called the “economy”, is falling down around the ears of everyone except the rich who have personal fortunes bigger than the GDPs of many countries, and that those most afflicted are vulnerable people who are copping all the associated injustice and grief. I’ve also been made to see how contaminated by money our ideas and behavior are, how even talking about it is indecorous and somehow suspect. You don’t talk about money problems because people might think you’re indirectly asking for a handout. I know money’s just a means of exchange, I say it’s not important, but it turns out I’m just as trapped in the fetishism as plenty of other people. In COVID-19 confinement, I’ve watched my income plummeting and have been wondering how I’m going to pay the rent. Even with a close and loving family, close and loving friends who were offering to help, I couldn’t accept it because I doubt that I could pay it back. My form of escapism was telling myself fatalistically that many of us are in the same boat, as if we were going to start a revolution or something.

Why can’t I accept help from people I love? Pride? Still trying to prove that I’m a strong, independent woman, as if that’s an image that can’t include cracks? I’ve always said that if I won the lottery, I wouldn’t change my life but would have a lot of fun distributing the winnings among friends and family. I mean it. I don’t want to change my life. It would be good if it was a little less precarious (literary translators don’t earn much and what we do earn is highly sensitive to the vagaries of the “market”), but I’d like to keep living as I am. I’d like to be able to give more but, at the ripe old age of seventy-five, I’m still being pig-headed about asking for help, talking about the worry of being able to pay the rent, and receiving. Why do I want to give but not receive? Anyway, to avoid thinking about this “shame” or “pride” nonsense, I organized all the residents in my building to demand a 70% drop in rent from the owner, one of Barcelona’s biggest real-estate holders. Watch (for the dust that will be kicked up in) this space…

One of the nice things about being in quarantine is that a lot of old friends have reappeared in emails and phone calls. A couple of old lovers too, still loving. I was quite chuffed. I thought, hell, even at this advanced age I’m still enjoying my old boyfriends! Love is another thing we don’t talk about much. It’s supposed to be private. Like money. It’s a commodity, packaged up with rules about fidelity, exclusiveness and, as Hollywood would have it, something for the young and beautiful. Jealousy and possessiveness are also part of the deal. But what if we started talking a lot more about how important it is to love and be loved? And all the ways of loving?

I’m going to try to start here. I’ve been in love with the same man for forty-five years, but we’ve never been able to live together for reasons totally beyond our control. Yet, when we’re together, we don’t know where one ends and the other begins. We’ve only spent a total of few months under the same roof over all these years. Meanwhile, we get on with our lives. If I can’t live with him, I don’t want to live with anyone. But that love has never debarred other relationships. “In love” with him doesn’t rule out “love” or sex with others. What he and I have is unique. Nothing can impinge on what we’ve managed to create for ourselves. That is our fidelity.

I always liked the idea that some languages have many words for love. It’s said that Sanskrit has ninety-six. I wanted to try as many as possible. So, when my two former lovers wrote, after years of no contact, to see how I was faring with the lockdown, I was happy. We’d split up, but all the good memories were still there. Yet I thought that, with R, I had to be careful. I was happy to hear from him, appreciated his concern, but I gave little back. I wasn’t generous. I wrote a fairly terse reply saying thanks, I was OK, a bit worried about having no work, but everything was fine. His first email had also been brief and careful. So, his response to mine was a surprise. It was succinct: “send me your telephone number and your account number please”. Talking to a friend about this, I wallowed in my capitalist hang-ups. I didn’t know what to do. I was shocked at his bluntness. I said I should never have mentioned being worried about work. What did he want? But I sent him my phone number.

I met him just over twenty years ago, in Timor-Leste, a couple of months after the Indonesian militia had, in a murderous rampage, displaced some 500,000 people, killed up to 7,000, and destroyed most of the country’s infrastructure, turning the eastern side of a beautiful island into ashes and rubble. It was the last day of my trip looking for a project to be funded with Catalan government money. A senior UN official told me that I should meet another UN man who was working in education. I’d heard of him as someone who was very brave and who’d risked his life getting people to safety in the UN compound, but I tried to get out of meeting him. I was interested in rural development, not education. I had very little time left and other people to see. But the UN man insisted. He dropped me off at a large fire-gutted building where, all alone on the first floor, R was sitting in a corner at a tiny desk, trying to catch the last light of the afternoon through a broken window as he was writing, with biro and notepad, a national plan for education. He seemed unsurprised by my unannounced visit and, without further ado, said, “Now you’re here, you can help me. I need some feedback.” So, we talked about education.

I went back six months later, this time with a friend, to study the possibility of funding a wet rice and buffalo project (which went ahead and ended up feeding thousands of people). I met R again and he invited us to dinner. It was awkward. He insisted on going to the floating hotel for foreign NGO workers (complete with salsa bars and Jacuzzi) when we wanted to go to the beach and buy fish from homeless local people who had lit fires and were grilling their small catches, in the hope of making a little money. The contrast was brutal. I wasn’t very nice. I ticked him off for not speaking Tetum when he had such a responsible position. Then, at the end of the evening, on the top deck under a sky throbbing with bright stars, he blurted out a long, very sad love story. We were stunned and not sure how to respond. I felt we should offer a story in return, but his was too overwhelming.

Not long after I got back to Barcelona, R phoned. He said, “I’ve got two things to tell you. I’m learning Tetum and I’m coming to visit you.” That was the start of an affair that lasted on and off for ten years. He returned to Washington and we visited each other. I broke it off three times and now I’m not really sure why. He knew that I was in love with another man but was willing to accept what I could give him. The last break was eight years ago.

There was no response from R for a few days after I sent him my phone number. I started to worry. Did he have the virus? I was being irrational. I hadn’t spoken to him for years, had no idea of what had happened to him in that time (and some tragic things had happened, as I found out) and now I was worrying about the virus. I sent another brief email saying I was surprised he hadn’t phoned and asking if he was alright. He wrote back at once saying he had a problem with his voice after being throttled, robbed, and left for dead in Addis Ababa last year, and that he felt self-conscious. He wanted to warn me about that before phoning.

When he phoned from Dallas, I could hear that it is an effort for him to speak but he is still huskily eloquent. He said, “You didn’t send me your account number. I want to help. I love you. I want to do it for me more than for you.” It was the old R, the one who has an Eritrean saying for everything. “A dead elephant isn’t scared of rain.” “It’s not the dagger that does harm but the idea behind it.” He was candid in expressing his love. It was as if there were no eight years of silence. He was so gracious he made accepting easy. He said I was doing him a favor. Now I know that he couldn’t sleep that night and that he was at the bank first thing the next day. He wanted to make sure the transfer was done properly. He told the teller he was helping a friend he loved. She jumped out of her chair and kissed (in coronavirus times!) him. The next day, more or less the equivalent of a month’s rent had landed in my bank account from Dallas.

R has taught me a great deal these last few days. He said, “I never gave up. It was never over for me.” I’d been mean in the way I broke with him. I said it was finished and didn’t want to talk about it, but here he was expressing his love yet again, without any defenses. His generosity is much bigger than anything to do with money. He taught me how to accept money as if it wasn’t money but something else, something much better. He gave unselfish love. That is impossible to reject. He showed how not being able to ask for or accept help is one more expression of how the wretchedness of capitalism has seeped into us. If we had a true community, a society in common, asking for and accepting help should be as natural as breathing. It is like that for R. He once told me about his childhood in Asmara where the family sat on the floor around a circular woven tray of food (meadi in Tigrinya, meaning “to be shared” and denoting at once the food, the tray, the people sitting around it and the social process that this entails) to which any comer was welcome. Everybody, down to the smallest child, knew exactly how much to reduce his or her portion to accommodate the guest. You didn’t need to ask. Everyone knew that if you dropped in at mealtime, the food would be shared. R, always true to his values, made a space for me at the meadi, and says, “Thank you for providing the opportunity”.

I wonder how many of the ninety-six words for love we can explore in the waning years of our lives.