Photograph Source: UK Government – OGL 3

There is a story about an enthusiastic American who took a phlegmatic English friend to see the Niagara Falls.

“Isn’t that amazing?” exclaimed the American. “Look at that vast mass of water dashing over that enormous cliff!”

“But what,” asked the Englishman, “is to stop it?”

My father, Claud Cockburn, used to tell this fable to illustrate what, as a reporter in New York on the first day of the Wall Street Crash on 24 October 1929, it was like to watch a great and unstoppable disaster taking place.

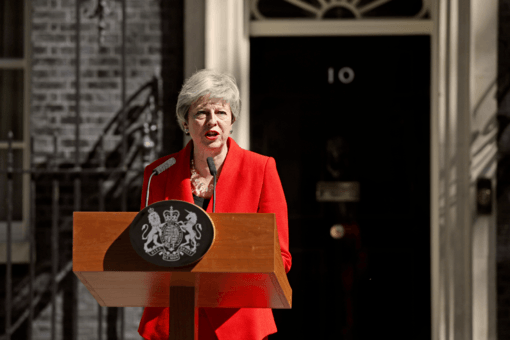

I thought about my father’s account of the mood on that day in New York as Theresa May announced her departure as prime minister, the latest milestone – but an important one – in the implosion of British politics in the age of Brexit. Everybody with their feet on the ground has a sense of unavoidable disaster up ahead but no idea of how to avert it; least of all May’s likely successors with their buckets of snake oil about defying the EU and uniting the nation.

It is a mistake to put all the blame on the politicians. I have spent the last six months traveling around Britain, visiting places from Dover to Belfast, where it is clear that parliament is only reflecting real fault lines in British society. Brexit may have envenomed and widened these divisions, but it did not create them and it is tens of millions of people who differ radically in their opinions, not just an incompetent and malign elite.

Even so, May was precisely the wrong political personality to try to cope with the Brexit crisis: not stupid herself, she has a single-minded determination amounting to tunnel vision that is akin to stupidity. Her lauding of consensus in her valedictory speech announcing her resignation was a bit rich after three years of rejecting compromise until faced with imminent defeat.

Charging ahead regardless only works for those who are stronger than all obstacles, which was certainly not the case in Westminster and Brussels. Only those holding all the trump cards can ignore the other players at the table. This should have been blindingly clear from the day May moved into Downing Street after a referendum that showed British voters to be split down the middle, something made even more obvious when she lost her parliamentary majority in 2017. But, for all her tributes to the virtues of compromise today, she relied on the votes of MPs from the sectarian Protestant DUP in Northern Ireland, a place which had strongly voted to remain in the EU.

Her miscalculations in negotiating with the EU were equally gross. The belief that Britain could cherry pick what it wanted from its relationship with Europe was always wishful thinking unless the other 27 EU states were disunited. It is always in the interests of the members of a club to make sure that those who leave have a worse time outside than in.

The balance of power was against Britain and this is not going to change, though Boris Johnson and Dominic Raab might pretend that what has been lacking is sufficient willpower or belief in Brexit as a sort of religious faith. These are dangerous delusions, enabling Nigel Farage to sell the idea of “betrayal” and being “stabbed in the back” just like German right-wing politicians after 1918.

Accusations of treachery might be an easy sell in Britain because it is so steeped in myths of self-sufficiency, fostered by self-congratulatory films and books about British prowess in the Second World War. More recent British military failures in Iraq and Afghanistan either never made it on to the national news agenda or are treated as irrelevant bits of ancient history. The devastating Chilcot report on Britain in the Iraq War received insufficient notice because its publication coincided with the referendum in 2016.

Brexiters who claim to be leading Britain on to a global stage are extraordinarily parochial in their views of the outside world. The only realistic role for Britain in a post-Brexit world will be, as ever, a more humble spear carrier for Trump’s America. In this sense, it is appropriate that the Trump state visit should so neatly coincide with May’s departure and the triumphant emergence of Trump’s favourite British politicians, Johnson and Farage.

Just how decisive is the current success of the Brexiters likely to be? Their opponents say encouragingly that they have promised what they cannot deliver in terms of greater prosperity so they are bound to come unstuck. But belief in such a comforting scenario is the height of naivety because the world is full of politicians who have failed to deliver the promises that got them elected, but find some other unsavoury gambit to keep power by exacerbating foreign threats, as in India, or locking up critics, as in Turkey.

Britain is entering a period of permanent crisis not seen since the 17th century. Brexit was a symptom as well as a cause of divisions. The gap between the rich and the poor, the householder and the tenant, the educated and the uneducated, the old and the young, has grown wider and wider. Brexit became the great vent through which grievances that had nothing to with Brussels bubbled. The EU is blamed for all the sins of de-industrialisation, privatisation and globalisation and, if it did not create them, then it did not do enough to alleviate their impact.

The proponents of Leave show no sign of having learned anything over the last three years, but they do not have to because they can say that the rewards of Brexit lie in a sun-lit future. Remainers have done worse because they are claiming that the rewards of the membership of the EU are plenteous and already with us. “If you wish to see its monument, look around you,” they seem to say. This is a dangerous argument: why should anybody from ex-miners in the Welsh Valleys to former car workers in Birmingham or men who once worked on Dover docks endorse what has happened to them while Britain has been in the EU? Why should they worry about a rise or fall in the GDP when they never felt it was their GDP in the first place?

May is getting a sympathy vote for her final lachrymose performance, but it is undeserved. Right up to the end there was a startling gap between her words and deeds. The most obvious contradiction was her proclaimed belief that “life depends on compromise”. But it also turns out that “proper funding for mental health” was at the heart of her NHS long term plan, though hospital wards for the mentally ill continue to close and patients deep in psychosis are dispatched to the other end of the country.

The Wall Street Crash in 1929 exposed the fragility and rottenness of much in the United States. Brexit may do the same in Britain. In New York 90 years ago, my father only truly appreciated how bad the situation really was when his boss said to him in a low voice: “Remember, when we are writing this story, the word ‘panic’ is not to be used.”