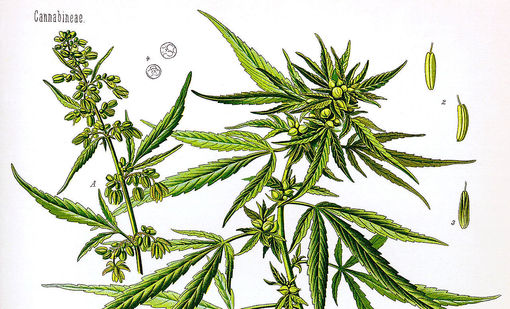

Image Source: Walther Otto Müller – Public Domain

A California Story with Senior Citizens, Pot Heads, Right Wingers, Vietnam Veterans, Female Firebrands and NORML

“We’re twenty years behind the rest of the Bay Area, and we’re playing catch up.”

– NORML’s Greg Kremenliev, May 2019

When Greg Kremenliev moved to Contra Costa County in 1983, he didn’t realize the depth and the intensity of the local opposition to cannabis. Nor did he foresee that his home county would become a battleground in the long, protracted war between prohibitionists on the one hand, and on the other hand pot smokers who believe in the right to self-medicate and who remind their fellow citizens that cannabis became legal in 2016, and that the industry is now regulated by Sacramento bureaucrats and local officials. An hour or two from downtown San Francisco at rush hour, Contra Costa can feel like it’s not really a part of the Bay Area.

Over the course of the last decade or so, the battle lines in the county have been emblematic of the war for and against cannabis that have been fought, sometimes along ethnic and class lines, all across the state of California, which produces far more marijuana than any other state in the U.S.

In 1983, when Kremenliev arrived in the city of Concord, opposition to cannabis was not limited to Contra Costa County. It existed in all 58 counties. Historians tend to forget that California was the first state in the U.S. to outlaw cannabis (in 1913), which was often cultivated by Mexican women, especially in and around L.A.

1913 probably seems like ancient history, but it wasn’t that long ago, in the dark days of Reagan Era, that the U.S. was caught up, with ample federal and state funding, in a war on drugs that included a war on cannabis and that led to the arrest and possession of marijuana and jailed. Unlike Humboldt and Mendocino Counties—and the whole “Emerald Triangle” in northern California, a major cannabis growing area all through the 1980s—Contra Costa didn’t have large-scale guerrilla operations and no major helicopter raids on gardens, either.

In the 1980s, Proposition 215—which legalized medical marijuana—was a long way from becoming a ballot initiative. So was Prop 64 that paved the way in 2016 for adult use of cannabis, aka “recreation use.”

For decades, like many other California cannabis users, Greg Kremenliev rolled joints and smoked them in  private. He certainly didn’t flaunt the use of his drug of choice. Contra Costa potheads often drove an hour or more—and passed through the onerous Caldecott Tunnel—to buy an ounce. Today, many of them say that they often felt they had to go through a gauntlet to get weed.

private. He certainly didn’t flaunt the use of his drug of choice. Contra Costa potheads often drove an hour or more—and passed through the onerous Caldecott Tunnel—to buy an ounce. Today, many of them say that they often felt they had to go through a gauntlet to get weed.

From Kremenliev’s point of view, Contra Costa still has a long way to go to normalize the use of cannabis. “We’re twenty years behind the rest of the Bay Area, but we’re playing catch up,” he says.

Kremenliev has helped the county pull closer to places like Berkeley and Oakland—home to the cannabis powerhouse Oaksterdam University—though for most of his adult life he wasn’t a cannabis activist, and didn’t stick his neck out.

“For years, I worked and raised a family,” he says. “Then one day I woke up and told myself that I was going to get involved in the cause.”

Little by little he did just that. On a night in July 2017, he set foot in Concord City Hall, when the council adopted one of many anti-cannabis resolution, and where he also met Arya Campbell, who had founded the Contra Costa chapter of the National Organization for the Reform of Marijuana Laws (NORML), the oldest and longest running pro-pot group in the nation.

Kremenliev, 71, is now the co-director, along with feisty Renee Lee, of the Contra Costa County chapter of NORML. Now approaching 70 and a retired therapist, Lee is also the founder and president of the Rossmoor Medical Marijuana Education and Support Group, which got off the ground in 2011 and is still going strong.

Over the last couple of years, Kremenliev has worked closely with Campbell and Lee, who lives at Rossmoor—a retirement community for elders 55 years and older. They are joined by more than half-a-dozen local citizens: Rebecca and Timothy Byars, Eloise and David Thiesen, Mark Unterbach, Tess Schoenbart and Laurie and Matt Light.

Lee views “Contra Costa as a law and order community,” though she also points out that people have been growing marijuana in the hills of the county for decades, and using it for just as long. A pot smoker starting in the 1960s, she has helped to educate dozens of Rossmoor seniors, some of them with dementia and Alzheimers, about the medicinal benefits of cannabis, “about how to smoke it and how to be THC friendly.”

Edi Birsan also joined the cannabis cause and exerted considerable influence after years of experience as a political figure in the county. In 2018, he served as the mayor of Concord, the largest city, population-wise, in Contra Costa. Once a gold rush town, Concord is now a suburban center near the geographical heart of the county. On the west side, Contra Costa tends to be liberal and a part of the liberal mindset of the Bay Area. On the east side, which is a gateway to the agricultural Central Valley it tends to be conservative.

In that way, Contra Costa is emblematic of the state as a whole.

In 2018, when Edi Birsan was the Mayor of Concord, he reached out to the owner of the one and only registered cannabis delivery service in the city, who raised eyebrows when he told a packed meeting that in a population of about 125,000 there were probably 40,000 cannabis users. Many purchased weed from a dealer in the unregulated market.

With all of his natural aplomb and local pride, Mayor Birsan announced, “I don’t want people to buy their pot anywhere but here.”

In a region where “local” carries a great deal of cache, the idea of a multi-faceted, local cannabis industry appealed to many citizens, including seniors 55 and over who lived at Rossmoor in Walnut Creek and who belonged to the medical marijuana support group Renee Lee started.

As battle lines were drawn, Rossmoor seniors came out of their cannabis closets. At a packed meeting in 2017, Rebecca Byars said that she and her husband had been running “an illegal delivery service for years.” Another senior, known for her big heart, told the city council, “You’d better hope that when you are our age, the people who are sitting in the seats where you sit will have more compassion for you than you have shown for us.”

The council ignored the pleas for compassion and voted to ban marijuana dispensaries, delivery services and testing labs. That vote extended and amplified previous bans in 2005 and 2013 that applied to medical cannabis and outdoor cannabis cultivation.

Beyond Concord city limits, members of NORML encountered stiff opposition from the Pacific Justice League (PJL), a conservative group based in Sacramento with many Asian members who linked cannabis to opium and opioid addiction. PJL helped block the opening, in San Francisco’s Sunset District, of the Apothecarium, a cannabis business founded by former Oakland Mayor Jean Quan, and her husband, Floyd Huen.

“PJL is a shadowy group,” Kremenliev says. “They had a dog and pony show they took to two Contra Costa cities, Lafayette and Walnut Creek, to influence citizens. The Southern Poverty Law Center designated it as a ’hate group.’”

In part, in response to PJL, Kremenliev and others came out of their cannabis closets, attended meetings, spoke out and helped strengthen NORML in Contra Costa.

Something happened, and while it’s not clear exactly what, it is clear that the thought of revenue from the sale of cannabis persuaded officials to flip from con to pro.

Lee says that after citizens approved a countywide measure to put a tax on marijuana, doors began to open and local bureaucrats became more receptive to the idea of dispensaries. It might have helped that Gavin Newsom, who was running for governor and who was an advocate for legalization, came to the county to speak about cannabis.

Kremenliev recalls “meetings between people on both sides of the political divide, and behind-the-scenes activity that resulted in key figures changing their minds.”

He has been around the cannabis industry long enough to know that “changes can happen very quickly” and that “it’s always something.” The current mayor isn’t receptive to cannabis, though the county now has three dispensaries, all in the city of Richmond which has a large African-American population (about 25%) and that now has a Green Party Mayor in Gayle McLaughlin.

Moreover, the city of Concord has authorized 10 cannabis licenses for testing, manufacturing and distribution of cannabis. Concord is considering a license for a dispensary. Kremenliev and some of his friends are starting a cannabis testing service to help ensure that consumers can buy quality product.

Contra Costa might have warmed to cannabis sooner than it did, and had more integrity as the pot prohibition was eroded. Not surprisingly, Vietnam Veterans played a key role.

“They had stories to tell,” Kremenliev says. “When they spoke they commanded a lot of attention and they helped to change the ways people were thinking.”

Along the way to cannabis legalization, decriminalization and acceptance, albeit lukewarm, Kremenliev has had his share of fun.

“We did a cannabis education day at Todos Santos Plaza in downtown Concord,” he says. “With help from longtime cannabis activists, Chris Conrad and Mikki Norris, NORML members also stood on the steps of the country courthouse in Martinez and gave away pot to anyone with ID that showed they were 21 or over. The police drove by. Our lawyer was there just in case.”

Kremenliev pauses a moment and adds, “You know it’s legal to give away up to an ounce.”

Who said there was no free pot anymore? Not outside the county courthouse, where the spirit of generosity fills the air, along with the aroma of homegrown, organic cannabis.

Jonah Raskin is the author of Marijuanaland: Dispatches from an American War