The world has survived the first year of United States President Donald Trump’s reign. He has not yet destroyed the world with a major war, whether against Iran or North Korea. He has not wrecked the foundations of the world trade and financial systems. These he has not done.

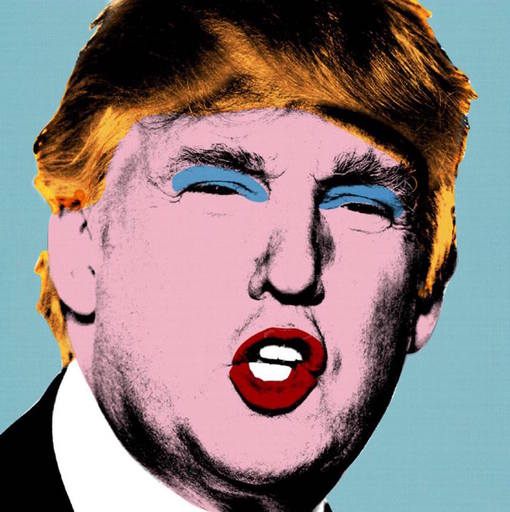

But, in this brief year, he has certainly emboldened elements of the hard Right, which had previously existed at the edge of the political sewer. He has pushed to the forefront socially toxic attitudes that had previously been hidden from public sight by a veneer of politeness. It is not clear whether Trump is the author of these maladies or if, as is more likely, he is merely one more illustration of them. Hatred has made its appearance as an acceptable political force. Trump is merely one more manifestation of this toxicity.

But during his first year, Trump pushed through a tax reform package that will make the rich richer and the poor more vulnerable. That was perhaps his most important achievement. Others have been blocked one way or the other. He could not start his war against Iran, nor could he move the U.S. embassy from Tel Aviv to Jerusalem. He was not able to dismantle the U.S. health care system, nor was he able to fully end the mild U.S. commitment to refugees. Much that Trump has done will be unpleasant for the country, but little of it is dramatically different from what has come before.

Protests

Just after Trump assumed office in January 2017, at least half a million people took to the streets in Washington, D.C. as part of the Women’s March. There was less clarity in what the marchers wanted than what they did not want—the presidency of Donald Trump and the implementation of his agenda. There was ferocious disdain for Trump’s crude sexism and racism, and there was hope that public pressure such as this would constrain the political class from converting Trump’s agenda into law.

During the course of the year, each time Trump put forward a particularly nasty public policy initiative—the Muslim ban, the end to protection for undocumented children—the same groups that took to the streets for the Women’s March came forward. It was the protests at the airports that put pressure on the judges to stay Trump’s hand. These have not, therefore, been symbolic demonstrations. These are statements that come with teeth.

Many of the people who joined these protests had little previous experience and little exposure to the wide range of political issues that confront the country. Clarity on police brutality and on wars of aggression was not available. It will take time for these movements to deepen their assessment of the problems in the country and to widen their appeal to those who remain outside their orbit.

A year into the Trump presidency, the Women’s March returned. The numbers were smaller, but the energy was sharp. Small towns, even in deeply Republican States, held marches. Over half a million people took to the streets of Los Angeles, California, where film stars joined labour union organisers in a large jamboree.

Two issues took centre stage at the 2018 protests—the #MeToo dynamic and the upcoming elections. It was inevitable that the question of sexual harassment and gender discrimination would be at the forefront. This was, after all, the Women’s March and it raised these issues last year to confront Trump’s vivid and unapologetic sexism. But this time the question of sexism was deeper, more personal, much more damning.

#MeToo

Outrage at sexual harassment and gender discrimination has a long history. But, in the recent period, a series of high-profile cases have brought these questions to the forefront—cases of both structural gender discrimination and sexual harassment.

During the last presidential election campaign, the Democratic candidate Hillary Clinton frequently raised the issue of the gender pay gap. In the United States, women are paid just 80 per cent of what men are paid for the same job—that is a 20 per cent pay gap. There have been changes since the 1960s, but these have been very slow. If the rate of closing the gap remains what it has been since 1960, the gap will not be closed until 2059. Political action, therefore, is imperative. Hillary Clinton had made this one of the cornerstones of her campaign. Class action lawsuits against Wal-Mart and Google raised awareness of the commonness of gender pay discrimination.

Public knowledge of sexual harassment was sharpened by allegations against the actor Bill Cosby, who was said to have drugged women before he raped them. What Cosby, a beloved figure on television, had done was universally derided as disgusting. When stories began to surface that Trump behaved in a similar manner, disgust over his presidential candidacy rose. But it did not seem to have much impact on the election. He won.

The victory of Trump led to an outpouring of angry recountings by celebrities and ordinary people of their own personal experiences with sexual harassment and sexual violence.

This “#MeToo” campaign raised many issues. Some people argued that naming names of offenders did an injustice to them since they were not being given the chance to be seen as innocent until proven guilty in a court of law. Others argued that these men were insulated from legal proceedings because of their political and financial power. Many had intimidated women into signing confidentiality agreements that seemed to shield the men from charges of sexual harassment. Accounts of the film producer Harvey Weinstein’s behaviour flooded into the public sphere and then opened the doors to other powerful men being challenged for their various forms of violence and inappropriateness.

This #MeToo dynamic played a major role in the Women’s March of 2018. In Los Angeles, the actor Viola Davis said: “I am speaking today not just for the Me Toos, because I was a Me Too. When I raise my hand, I am aware of all the women who are still in silence.”

‘Power to the Polls’

In 2017, the protests were against the Trump agenda. Midterm elections will be held in 2018, so this time the focus moved from anger towards elections. The slogan before the marchers was “power to the polls”. At present, the Republican Party controls the White House, the U.S. House of Representatives, the U.S. Senate, as well as a majority of State Houses. The U.S., in other words, is dominated by the power of the Republican Party.

This year’s midterm elections will be fundamental for the resistance to Trump. Each and every one of the 435 members of the House of Representatives will be up for re-election, as will a third of the U.S. Senators. A majority of the Governors in the States will face elections. If the Democratic Party could whittle away at the Republican control of these offices, Trump will be weakened. But it is unlikely. Seats have been utterly gerrymandered—in other words, districts have been drawn in such a way as to ensure Republican control of the House of Representatives at least, if not other offices.

Furthermore, political alignments do not necessarily suggest that the hundreds of thousands of people who take to the streets command a majority in the country. This was known as the Women’s March. And yet, in the last presidential election, Trump—despite his vividly sexist behaviour and remarks—won a majority of the votes of white women. A striking 62 per cent of white women went for Trump, while 95 per cent of black women voted for Hillary Clinton. If black women and non-white women in general (81 per cent) had not voted for Hilary Clinton, she would not have been able to win the women’s vote.

It is remarkable that the first woman candidate, a candidate who ran on women’s issues, was not able to win over white women to her side. There is little guarantee that they would vote for the Democrats this time around.

This article originally appeared on Frontline (India).