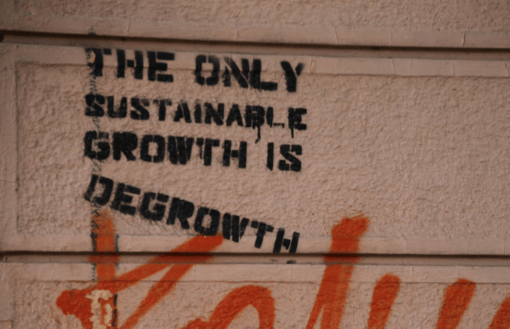

Photo by Paul Sableman | CC BY 2.0

The economist Branko Milanovic recently wrote a blog post titled “The illusion of degrowth in a poor and unequal world.” He penned it, he says, following a conversation he had with a proponent of degrowth.

As it turns out, that proponent was me.

First, let me say that I have a lot of respect for Milanovic’s work on inequality. I cite him all the time. But unfortunately he doesn’t have a strong grasp of degrowth. Let’s look at his argument in detail:

Milanovic rejects degrowth because he believes it is unfeasible. He notes, correctly, that if we were to cap global GDP at its present level then the only way to eradicate poverty would be through redistribution: reduce the income share of the richest and shift it to the poorest. He thinks this is a terrible idea. If we bring all of the poorest up to $5,500 per person per year (the global mean income), then in order to stay within the GDP cap everyone above this level (almost all of whom live in the West) will have to take an income cut, with the richest taking the biggest hit. This would also require “gradual and sustained reduction of production” in rich nations, with economic activity slashed to one-third of its present size.

Milanovic calls this “the immiseration of the West,” and he dismisses it as “not even vaguely likely to find any political support anywhere.” Forget about it, he says; we need growth. Let’s focus instead on reducing our consumption of emissions-intensive goods and services by taxing them, and “think about how new technologies can be harnessed to make the world more environmentally friendly.”

This is exactly the argument that Milanovic articulated during our email exchange. I responded by pointing out some of its problems and by gesturing in the direction of relevant literature he might find useful, but he never replied. Apparently he had made up his mind, and was ready to take a public stance. So let me publicly lay out some thoughts in response.

Degrowth does not call for immiseration.

Milanovic’s argument is leveled against a straw man. If he had read the literature on degrowth, he would know that it does not call for immiseration.

Imagine cutting the GDP per capita of the US down to less than half its present size, in real terms. This might sound horrible on the face of it, but it would be equivalent to US GDP per capita in the 1970s. Folks who lived through the 70s remember them as heady days. And the poverty rate was lower back then – and happiness levels higher – than now. Real wages were higher, too. The only difference is that people consumed less unnecessary stuff. It’s not clear why Milanovic considers this to be so dreadful.

There are lots of other examples we might cite. The GDP per capita of Europe is 40% lower than that of the US. I live in Europe: it is hardly a dystopia. Costa Rica has a GDP per capita that is one-fifth that of the US, but it has life expectancy that outstrips that of Americans, and levels of happiness that rival those of Scandinavians. All of these examples prove that we don’t need ecology-busting levels of income and consumption to live good lives. The literature is very clear on this: just check out Tim Jackson’s Prosperity Without Growth, Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful, Firamonti’s Well-Being Economy, Raworth’s Doughnut Economics, or anything by Giorgos Kallis.

In fact, degrowth calls for human flourishing.

Proponents of degrowth don’t just want to redistribute income within the already-existing economy, as Milanovic wrongly assumes. We want to redistribute income in a way that improves social goods, like universal healthcare and education, which are key to reducing poverty and improving people’s lives. Not only are universal systems cheaper and more efficient at achieving these outcomes than private ones (healthcare in the UK costs one-third that in the US), but having them in place also improves the “purchasing power” (if you will) of incomes. Think about it: if Americans didn’t have to pay exorbitant prices for healthcare and higher education, they would need a lot less income to live good lives.

In this way, decommoditizing key social goods is a good way to take pressure off the planet. We can even extend this insight to housing. Housing in London, where I live, is obscenely expensive. Most people spend half of their income just to keep a roof over their heads. If the housing stock was even partially decommoditized, Londoners would be able to work much less than they do now – producing less unnecessary stuff in the process – and still have the same quality of life that they presently enjoy.

Degrowth demands a different kind of economy.

Of course, all of this requires that we shift to a different kind of economy altogether – one that supports and promotes the commons, and focuses on improving human well-being rather than only on improving monetary incomes. This is where Milanovic makes a key mistake. The point of degrowth is to reduce the material throughput of the economy not by shrinking the existing one (which would surely be painful), but by shifting to a better one: one more in line with our planet’s ecology.

To be honest, I’m surprised that Milanovic didn’t jump on a more obvious issue, namely, that if our economy stopped growing it would more or less immediately bump up against financial crisis. Why? Because our economy is shot through with debt, and debt comes with interest; and because interest is a compound function, all of us have to run around producing more and more each year, shoveling money into the pockets of the rich, just to pay it down. If we halt the rat race, the whole house of cards will collapse. And it doesn’t help that, given fractional reserve banking, our money system itself is based on debt.

So if we want to throw off the tyranny of growth we’ll have to have some kind of debt jubilee, and get rid of our debt-based money system. These necessary changes are not compatible with the logic of the existing economy. We need a different kind of economy.

Trying to eradicate poverty through growth is going to immiserate everyone.

Milanovic rejects degrowth and claims that we should stick with the existing plan for eradicating poverty: more growth. But he hasn’t thought through the implications of this.

We need to remember that the existing distribution of global growth is skewed heavily toward the rich. David Woodward points out that even during the most equitable period of the past few decades, only 5% of new income from annual global growth went to the poorest 60% of humanity. At this rate of trickle-down, it will take more than 100 years to get everyone above $1.25 per day, and 207 years to get everyone above $5 per day. And in order to get there we will have to grow the global economy to 175 times its present size.

That’s 175 times more extraction, production and consumption than we’re already doing. And to reach Milanovic’s minimum of $5,500 per year would require much more than this by far. Even if this kind of growth was physically possible, it would cause catastrophic ecological crisis that would more than wipe out any gains made against poverty. Redistribution may not seem feasible to Milanovic, but the existing plan is much less feasible still.

Yes, one might argue that we can improve the share of growth that goes to the poorest. That would be an important first step, to be sure. But as long as the rest of the world continues to grow, increasing aggregate material throughput and emissions, we’re going to be in trouble. In fact, we’re already in trouble even at existing levels of throughput and emissions, and we can see it all around us: rapid deforestation, collapsing fish stocks, mass species extinction, soil depletion and of course climate change, with the poorest getting hit hardest by far.

Milanovic believes we can reign these problems in with more “environmentally friendly” growth. But that’s a pipe dream. And this brings me to my last point:

Green growth is not a thing.

Milanovic likes to run numbers, so let’s look at some.

First, emissions. As we know, emissions rise more or less in line with GDP growth. Climate scientists Anderson and Bows (2011) say that if we want to stay under 2°C, rich nations will have to reduce emissions by 8-10% per year. Since the dominant assumption in the literature is that reductions greater than 3-4% per year are incompatible with a growing economy (Stern 2006; UK CCC 2008; Hof and Vuuren 2009), they conclude that the only way to prevent catastrophic climate change is by reducing economic activity.

This conclusion is in keeping with that of other studies (e.g., Raftery et al 2017). Keep in mind that the existing rate of decarbonization is only about 1.6% per year. Schandl et al (2016) suggest that some rich nations might be able to bump this up to a maximum of 4.7% per year in the future if they roll out a high and fast-rising carbon price, and somehow manage to double their material efficiency. But even this extreme best-case scenario is a far cry from the 10% we need.

Of course, some think we’ll be able to buy time by deploying new technology, the most “promising” being bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). But there is a growing consensus that BECCS won’t work. The technology has never been proven at scale, and it probably won’t appear in time to prevent us blowing the 2°C budget (which is only 19 years away). Even if it did, it would require that we create plantations for biofuel equivalent to three times the size of India. Think about the consequences for the global food supply: hardly good for poverty-reduction.

But let’s be charitable and assume that Milanovic is right – that we can somehow manage to reduce emissions by reducing the consumption of high-emission goods and services. Of course, in order to keep the economy growing, we would still have to increase the consumption of other goods and services. Milanovic sees no problem with this. I don’t know why. Maybe he believes that new technology will make us more efficient, and we will be able to grow the GDP without growing material throughput.

This is known as “absolute decoupling”. But unfortunately absolute decoupling is not a thing. Take two recent studies:

Ward et al (2016) find that even the most optimistic projections of efficiency improvements yield no absolute decoupling in the medium and long term. The authors state: “this result is a robust rebuttal to the claim of absolute decoupling”; “decoupling of GDP growth from resource use, whether relative or absolute, is at best only temporary. Permanent decoupling (absolute or relative) is impossible… because the efficiency gains are ultimately governed by physical limits.”

Schandl et al (2016) find the same thing. Even in their best-case scenario projection, global material consumption still grows steadily. The authors conclude: “Our research shows that while some relative decoupling can be achieved in some scenarios, none would lead to an absolute reduction in energy or materials footprint.”

I laid all this evidence out for Milanovic, but he didn’t engage with it. Instead, he chooses to believe, against all available evidence, that we can continue with indefinite exponential GDP growth without causing ecological collapse.

Milanovic accuses us – incorrectly – of wanting “the immiseration of the West” in order to eradicate poverty in the global South. But his blind faith in growth, and his implicit denial of scientific evidence, is sure to lead to ecological collapse – entrenching the misery of the poor and immiserating the rest of us in the process.

**NOTE: Milanovic responded to this post by insisting that degrowth is not politically feasible. But I disagree: people are ready for a new economy. See my argument here.

Jason Hickel is an anthropologist at the London School of Economics. He specializes in globalization, finance, democracy, violence, and ritual, and is the author of “Democracy as Death: The Moral Order of Anti-Liberal Politics in South Africa”.

NOTE: This essay originally appeared as ‘Why Branko Milanovic is wrong about de-growth‘, on Jason Hickel’s blog.