Dallas Cowboys owner Jerry Jones has figured out a way to fake solidarity with protesting NFL players, while kowtowing to President Trump and fans who worship the flag.

Prior to the playing of the national anthem at the September 5th game against the Arizona Cardinals, Jones joined his players, coaches and staff on the field in taking a knee and locking arms. But then he and his entire team stood at attention when “The Star-Spangled Banner” was played.

Trump tweeted his approval, noting that “while Dallas dropped to its knees as a team, they all stood up for our National Anthem. Big progress being made — we all love our country!”

The following day, he tweeted: “Spoke to Jerry Jones of the Dallas Cowboys yesterday. Jerry is a winner who knows how to get things done. Players will stand for Country!”

When kneeling players caused Vice President Mike Pence to walk out of the Oct. 8 game between the Indianapolis Colts and the San Francisco 49ers, Jones made clear his sham solidarity with the protesting players, promising that his team would never kneel during the anthem.

He told The Dallas Morning News: “If there’s anything that is disrespectful to the flag, then we will not play. Understand? We will not … if we are disrespecting the flag, then we will not play. Period.”

Trump again tweeted his applause. “A big salute to Jerry Jones, owner of the Dallas Cowboys, who will BENCH players who disrespect our Flag. Stand for Anthem or sit for game!”

Thus far, no Cowboys player has dared to disobey their owner’s command. But things weren’t always so conformist on “America’s Team.”

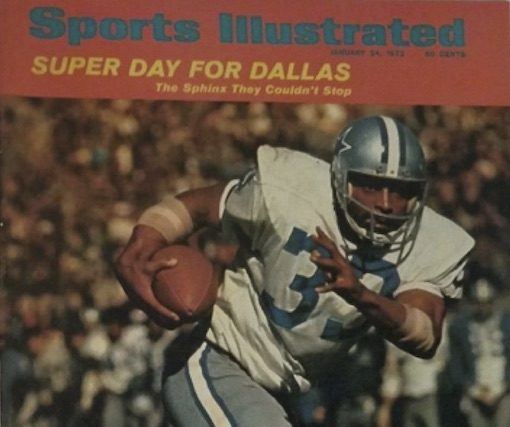

Almost 50 years ago, the Cowboys’ star running back, Duane Thomas, did far more than take a knee.

Thomas wasn’t protesting anything specific. No, he was more like Marlon Brando in The Wild One.

Hey Johnny, what are you rebelling against?

Johnny: Whadda you got?

Thomas “cracked the arrogance that has encased the Cowboys front office for years,” wrote his fellow rookie teammate, Pat Toomay, in his 1975 memoir, The Crunch.

As Toomay famously said at the time: “Duane Thomas has become for the Cowboys what Russia was for Winston Churchill: the proverbial enigma, wrapped in a riddle, doused with Tabasco, and stuffed in a cheese enchilada.”

Thomas cultivated an aura of mystery by rarely speaking to the media, earning him the nickname “Sphinx” among local sportswriters.

He also led the Cowboys to their first Super Bowl. It was 1970, his rookie season.

At the time, the Cowboys projected a uniquely wholesome image, guided by general manager and former PR man Tex Schramm, with devout Christian head coach Tom Landry anchoring the brand.

It would be several years before former Cowboys player Pete Gent exploded the myth with his novel North Dallas Forty.

By 1970, Gent and his fictionalized co-star, Don Meredith, were gone, but a new breed of non-conformists had taken their place on the roster.

Toomay was one of three Cowboys who made up the “Zero Club,” which also included defensive end Larry Cole and offensive guard Blaine Nye, the group’s founder and namer. During the offseasons, Nye earned a master’s degree in physics from the University of Washington, and an MBA from Stanford, where he also got a PhD in finance after starting in three Super Bowls with the Cowboys.

Nye, like Toomay, had a way with words. “Professional football is funny,” he once said. “It’s not whether you win or lose, it’s who gets the blame.” When a reporter asked him about blocking the Steelers’ legendary defensive tackle Mean Joe Greene, Nye quipped: “His strengths match up perfectly against my weaknesses.”

The Zero Club was a joke on the anonymity of linemen. Or something like that. As Toomay explained: “The philosophical undercurrents of the Zero Club eddy about the idea of enlightened indifference. The group is dedicated to ennui.” It “subscribes to Joseph Heller’s Boredom Cultivation Plan,” which enables its members to “add years to their otherwise truncated life expectancies.”

Then there was rookie Steve Kiner, a counterculture rebel from the University of Tennessee, who quickly became Thomas’ best friend on the team.

“The apartment that Duane shared with linebacker Steve Kiner was near Love Field, in the heart of a transient population of hustlers and airline stewardesses,” wrote Gary Cartwright in a 1973 article for Texas Monthly, based on a few days spent hanging out with the interracial odd couple. “Duane swallowed a handful of protein tablets to make his hair grow faster, and placed a stack of records on the stereo. After we had talked for a while, Kiner arrived with several friends and a bag of mescaline.”

Cartwright also recalled the time when a teenage blonde girl asked Thomas to autograph a sheet of her notebook paper, and he obliged by scribbling his name along with some Sly & The Family Stone lyrics.

Don’t hate the black, don’t hate the white.

When you get bit, just hate to bite.

When Thomas was interviewed during the hype-filled week leading up to Super Bowl V, he famously objected when a reporter referred to it as the “ultimate game.”

“Then why are they playing it again next year?” Thomas asked.

As fate would have it, Thomas turned out to be the goat of Super Bowl V. On the verge of scoring a touchdown that probably would have won the game, he fumbled on the goal line, and the Cowboys ended up losing 16-13 on a last-second field goal.

After the game, Thomas sphinxed out for good. The following season, Toomay wrote in his journal:

“Last year Duane would not speak to the press, nor would he answer the roll call in team meetings. This season he has thus far maintained the status quo; he hasn’t taken any meals with the team, nor has he spoken to the press or many of his teammates … From what I can surmise, his problem is basic: Duane is still pissed off at football.”

He did speak, once, to his teammate Mike “there has been no oppression in the last 100 years” Ditka.

“Once we were playing the Giants in Yankee Stadium,” Ditka recalled. “I always made a habit of going up and wishing everybody good luck before a game. I went up to Duane and just patted him on the back and said, ‘Good luck.’ He didn’t acknowledge it. The following Tuesday, I was sitting beside my locker reading the paper in Dallas before practice and he came up to me and said, ‘Hey man, don’t ever hit me on the back before a game. It breaks my concentration.’ I said, ‘Hey Duane, go fuck yourself.’ That was our conversation.”

At a press conference, Thomas called Tex Schramm “sick, demented and completely dishonest,” and diagnosed Tom Landry as “a plastic man … no person at all.”

The Cowboys responded by trading him to the New England Patriots. Within 24 hours, the Patriots cancelled the trade and sent him back to Dallas.

Thomas went on to play the 1971 season with the Cowboys, who paid him a salary of “about $20,000” that year, Toomay noted. It was a pathetically low sum, even for the Cowboys, who allegedly had the league’s most miserly payroll.

In spite of his low wages, Thomas led the team back to the Super Bowl that season, and this time they won, beating the Miami Dolphins 24-3. It remains the only Super Bowl in which one of the teams was held without a touchdown.

As Hunter Thompson wrote, Thomas “ran through the Dolphins like a mule through corn-stalks,” carrying the Cowboys to victory.

But the MVP award was given instead to the squeaky clean (and very white) Roger Staubach, who turned in an average performance by Staubachian standards.

After the game, Thomas briefly broke his silence in the locker room. With football legend Jim Brown standing mysteriously at his side, he gave one of the most memorable interview responses in sports history. When TV announcer Tom Brookshire asked him if he was as fast as he appeared, Thomas blankly replied, “Evidently.”

Just a few weeks after the Super Bowl VI win, Thomas was busted for marijuana possession, and he never again played for the Cowboys. He was traded to the San Diego Chargers before the 1972 season.

In return, the Cowboys received a white wide receiver named Billy Parks. For the Cowboys, it turned out to be a case of very bad karma.

“Parks was a tremendous receiver when everything clicked inside,” said Staubach in his book Time Enough To Win. “But football wasn’t his No. 1 priority.”

His No. 1 priority was left-wing politics. “Parks was anti-Nixon and anti-Vietnam War to an almost violent degree,” recalled Staubach, the Naval Academy graduate and Vietnam War veteran. “Before one of our games Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird held a military induction ceremony at Texas Stadium. When Parks saw that, he was so upset he almost refused to play.”

Parks told one reporter: “The way they try to promote [the game] and sell it is out of proportion to its value to society. The whole purpose is to make a buck, to get the fans. With the electronic media, they can make anything God-like.”

On Thanksgiving 1972, Parks and the Cowboys traveled to San Diego to play Duane Thomas and his new team.

Gary Cartwright described it in his Texas Monthly piece:

“While a national television audience watched with new anticipation, Duane Thomas trotted onto the field in a trance. Quarterback John Hadl tried to play catch with him, but after the first toss Duane placed the ball down in the end zone and walked off. While the rest of the team warmed up at the opposite end of the field, Duane took a stance with his hands on his knees and looked at the ground for 15 minutes. During the playing of the National Anthem, he walked around like a man lost on the moon.”

Thomas decided not to play at all that day, and instead sat by himself at the end of the bench for the duration of the game.

At the end of the season, the Chargers got rid of Thomas, sending him to the Washington Redskins, where coach George Allen had molded a group of “over the hill” veteran players into a team that reached Super Bowl VII.

At Washington, Thomas took up where he left off with San Diego. During a preseason game against the Buffalo Bills, he turned his back to the flag during the national anthem, severely pissing off patriotic Bills fans.

According to The Washington Post, Thomas “had to be restrained from climbing into the stands and fighting with spectators, who allegedly threw refuse and shouted obscenities at him.”

Like Jerry Jones, George Allen was an ardent Republican and close personal friend of the president (Nixon). Unlike Jerry Jones, George Allen didn’t need the flag to show what a big patriot he was.

“I honestly don’t know how he feels about the National Anthem,” Allen said of Thomas in an interview with The Post. “I sing the National Anthem myself. There will be no problem on the National Anthem. Usually, we do stand at attention. It’s no big deal.”

After two average seasons with the Redskins, Thomas in 1975 signed with the World Football League, which collapsed a month later. Although he made a few attempts at a comeback over the next four years, his career was effectively over.

Years later, Thomas told the Houston Chronicle that one of his favorite NFL memories was hearing The Temptations sing the national anthem during a game in Detroit.

David Bonner is co-author, Selling Folk Music: An Illustrated History (forthcoming 2018, University of Mississippi Press).