Bookshelves and enfilade: Nina Hoss and Cate Blanchett dance to Count Basie in Tár.

Amidst reports that the red-hot Berlin property market is cooling off (literally so, given the steep rise in energy prices) comes a new product placement fantasy that advertises upscale apartments in the German capital— writer/director Todd Field’s latest film, Tár.

This discerning ode to tasteful luxury interiors ranges from brooding contemporary concrete to crisp white Jugendstil stucco. Tar, with or without the accent, is not one of the construction substances of choice. We catch fleeting glimpses of roof tiles, but they are of old-world terracotta or the latest eco-friendly composites. Parquet floors glow through matte varnish in those places where they aren’t protected by the deep blues and reds of Oriental rugs. The countertops are to die for.

Clocking in at a spacious two hours and thirty-seven minutes, the film gives both the well-heeled apartment hunter and the merely curious plenty of time to look, lust, and count their Pfennigs.

Field’s extended-play advertisement does come with a story of sorts, but like the most effective commercials, this one traffics in mood and aspiration. Even if you wouldn’t want to be like the people in the film, might you at least like to live like them? Maybe not in every way, but if they’re selling (spoiler alert: they will be) and prices are dropping …

The title character is one of the world’s greatest conductors—Lydia Tár (Cate Blanchett). Not coincidentally, her first name evokes one of the ancient Greek musical modes. Indeed, she’s a Sapphic superstar—or, more accurately, a “U-Haul lesbian,” as she self-diagnoses early on. Big-time conductors, whether they like women, men, both or neither, move around a lot. Someone has to find their living quarters and schlepp their furnishings. In spite of the U-Haul boast, Tár is more the artistic director type than the woman behind the wheel or handling the dolly.

Even more impressive than the packing list, Tár’s curriculum vitae is a litany of prizes, posts, and degrees from prestigious institutions: the Curtis Institute and Harvard; Grammy, Academy, Emmy, Tony Awards. She’s not only a demi-goddess of classical music but has also written a Ph.D. dissertation on the music of an indigenous group in the Amazon.

We learn all this in the long opening scene, an interview with the New Yorker’s Adam Gopnik (played by himself) that begins with an extended introduction extolling her accomplishments and accolades and announcing her forthcoming memoir. When Gopnick finally gets to his questions, Tár answers one of them by telling him that any and all discoveries of musical interpretation happen only in rehearsal, never in performance. And so she delivers her grandiose pronouncements as if reading by rote from the score in her head. Blanchett is charged with portraying someone who has crafted her own monologues as a mediocre actor would. I’m not sure that the excruciating embarrassment she elicited in me was a signal triumph of the thespian’s craft or just an unavoidable byproduct of ham-fisted movie making.

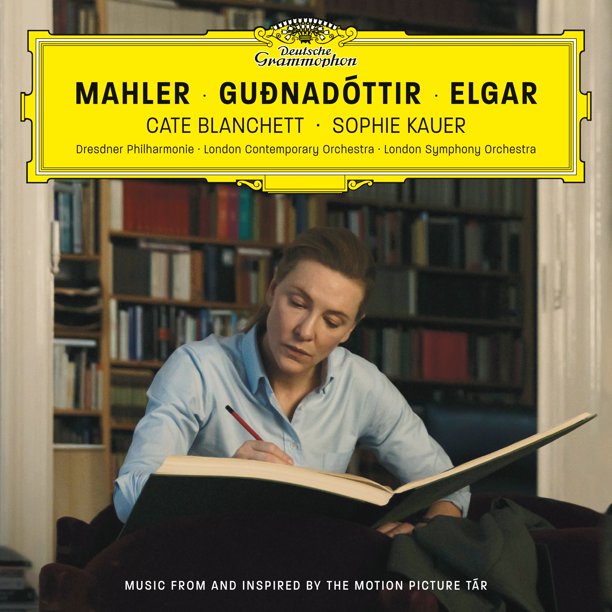

From the New Yorker Festival Tár is whisked off to a power lunch with a fawning fellow conductor and from there to a masterclass at the Juilliard School. In a boxy modernist cave of a chamber concert hall, she bullies a would-be conductor who identifies as BIPOC and who boycotts Bach’s music since it is the work of a dead white misogynist who fathered twenty kids. Lydia is having none of this, and also takes the opportunity to bully-in-absentia the composer whose music the kid is conducting—the Icelander Anna Sigríður Þorvaldsdóttir. (There’s more Icelandic music in the movie; the minimal soundtrack is from the Oscar-winning pen of Hildur Guðnadóttir.) Þorvaldsdóttir is a real person with a really big career and a Deutsche Grammophon contract and cool record covers. Cate Blanchett now has a DG cover too, though one a lot less cool.

As with the Gopnik set piece, the film’s fictions flirt with reality. It might just be that Tár’s withering treatment of the music and its young champion are driven by envy of all those Icelandic diacritical marks rather than by detached critical judgement.

Unbeknownst to Tár, her hectoring of the nervous, hapless fellow is being illegally filmed on an iPhone by one of the auditors. The fastidious control the conductor is able to exert over the musical score and her orchestral underlings does not extend to the chaos of social media. Tár may like the sound of her own voice when grandstanding against identity aesthetics within the snug confines of the Juilliard chamber hall, but she will be significantly less pleased once her masterclass performance is aired on the internet.

Others are surreptitiously filming her too, and when a scandal starts to boil over—Tár may have been preying sexually on young female conductors whom she coaches under the auspices of her foundation supposedly dedicated to fostering their careers—it proves increasingly difficult to keep the lid on. Reputations are a lot harder to protect than granite countertops. The attempts to scrub away the allegations lead to a board room visitation atop some high-rent commercial real estate overlooking Berlin’s Kulturforum and the Philharmonie. With toxic broth foaming, Tár clings to a false sense of security, distracted by art and ego even as inner demons and a mysterious metronome begin to haunt her.

On the podium before the world’s greatest orchestra, the Berlin Philharmonic, Tár is about to complete her Mahler project in a live recording in the city’s most famous concert hall, the Philharmonie, one of the most celebrated acoustic and architectural spaces in classic music. She will add her name (and her cover photo) to the catalog of legendary readings of the cycle, not least that by her mentor, Leonard Bernstein.

Tár’s office somewhere inside the Philharmonie is a den of now-trendy 1960s accoutrements and contours. From this redoubt she commands her musical empire, banishing the unwanted to distant frontiers and jiggering auditions so as to make sure that the hot new Russian cellist (Sophie Kauer) wins the place in the orchestra after she’s already won over Tár’s libido. Blanchett brings off the conducting scenes such that most of our disbelief can be reduced to mezzo piano. Much more persuasive is the representation of the isolating managerial machinations of the conductor. Even though Tár has what appears to be a model family, it’s lonely at the top. But this doesn’t excuse the ways she goes about getting unlonely.

Tár is married to a German woman, Sharon (Nina Hoss), who is also the orchestra’s concertmaster. We suspect that the the conductor’s charismatic power may have had more than a little to do with kindling Sharon’s attraction. The couple occupies vital positions at the top of the sometimes contentious orchestral hierarchy, but the conductor stands above all others. This imbalance inevitably sows domestic disharmony within their elegant, if moodily lighted apartment.

The pair’s adopted daughter (Mila Bogojevic) is odd, even troubled, not least because she is being bullied at school. Returning from her New York swing, Tár deals ruthlessly with the girl’s nemesis. Crouching down to the Kindergartner’s height and introducing herself as Petra’s “Papa,” Tár threatens the other girl in frightening, fairy tale German: “I will get you” (ich kriege dich). As in almost all of the movie, this chilling scene plays without underscoring. The music we do hear in the film comes from rehearsals in the Philharmonie and in the other immaculate Berlin apartment that Tár uses for study and seduction. The schoolyard scene makes clear what the movie’s main theme is: power. Music is merely an accessory, a countermelody.

The conductor’s schoolyard tactics also suggest that Tár is a veteran of scraps beyond the corridors of high culture. But her threats aren’t the most unsettling ones in the movie. Having neglected Petra in favor of her career, she makes an ominous promise: “I will teach her the piano.”

Like a conductor’s beat, fortunes rise and fall. Tár’s unraveling is told not with epic symphonic sweep but in fragments. An extended coda revisits the main themes: diacritical marks, real estate, décor, travel, sexual objectification, and, somewhere through the drugged haze of celebrity and money, a love of music that cannot be bought and sold—even when interest rates are low.