The public discourse over inequality and racial disparities has rightly shifted to how to dismantle structural challenges that create these gross inequities. Addressing racial disparities will require a concerted effort by government across all policy areas. A new report from the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) offers some perspective on how state and local tax policies fit into that picture.

Right now, the overwhelming majority of state and local tax systems are regressive, meaning they tax their lowest-income residents at higher rates than the top 1 percent. So it’s not surprising that they fall far short of their potential as tools for advancing racial equity. But there are some bright spots and plenty of options for reform that could make them more effective.

There are a few key elements to keep in mind when crafting racially equitable state and local tax codes. First, the system needs to raise enough revenue to fund deep investments in education, health, childcare, and countless other areas that are essential to advancing racial equity and building broadly shared prosperity.

Second, the tax code should be progressive, raising a significant amount of money from high-income individuals with the greatest ability to pay — an outsized share of whom are white. And third, it should be crafted in a way that does not advantage wealth over work.

Years of racism and discrimination across all segments of society — the housing market, labor market, financial industry, education systems, criminal justice, and other areas — have prevented people of color from building wealth on the same level as white families. States should be asking more of families who have seen their fortunes swell alongside our nation’s surging levels of inequality.

Far too many states, however, have chosen to shy away from progressive taxes on affluent families. To keep government running, they’ve chosen to lean heavily on consumption taxes instead. Sales taxes are the most regressive type of tax at the state and local levels because lower-income families have to spend much more of what they earn on basic expenses.

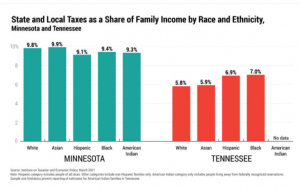

ITEP’s analysis shows that sales and excise taxes are also the most significant drivers of racial inequity in state and local tax codes. In Tennessee, for example, we find that the average Black or Hispanic family devotes about 5 percent of their earnings to paying these taxes, while the average white family devotes just 3.9 percent.

States have far better options than the sales tax at their disposal. Taxing personal and corporate incomes, estates and inheritances, and wealth more broadly can help counteract racial inequities.

Minnesota relies more heavily than most states on these types of revenue sources and we find that the state is managing to lessen racial income disparities through its tax code — a sharp contrast to Tennessee, where the tax code drives an even larger wedge between affluent white families and most people of color.

But even in Minnesota, enormous racial income and wealth gaps remain after taxes, and it’s clear that the state has far more work to do address those disparities. Recent proposals from Governor Tim Walz to boost taxes on top earners and investors would be a step in the right direction.

State and local taxes won’t be enough to close our nation’s unconscionable gaps in income and wealth across race. But by collecting those taxes fairly and spending the money wisely, they can make a difference in moving us toward a more just future.

Carl Davis is the research director and Meg Wiehe is the deputy executive director at the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP). Misha Hill is an independent consultant whose work focuses on how policy reforms can remedy racial inequities. They are co-authors of a new report, Taxes and Racial Equity: An Overview of State and Local Policy Impacts.