Gold Star Moms, the Great War, the Russian Revolution – and a memorial that nobody seems to remember or notice.

Veterans Day, November 11, 2017. This is the 100-year anniversary of the entry of the United States into World War I. It is also the 100-year anniversary of the Russian Revolution, at root an open mutiny against that war. Hidden away in Heroes Grove, an almost-forgotten part of Golden Gate Park, is the Gold Star Mothers Rock. This monument is a memorial to U.S. veterans who died in World War I, and has a surprising relevance to the Russian Revolution.

THE GREAT WAR

World War I began in 1914. Known at the time as the Great War, it became the most brutal and destructive war in history, up to then. Millions of soldiers and civilians died. It was a barbarian struggle by the imperialist powers of Europe – Britain, France and Germany chief among them – over their respective spheres of influence in Europe and control of their colonies in Africa and Asia. If there ever was a “rich man’s war” that was in reality “a poor man’s fight,” this was it.

On the eastern front, the decrepit Czar Nicholas II allowed Russia to be dragged into the war on the side of Britain and France. Russia’s troops, poorly led and even more poorly equipped, were killed and wounded by the millions. In March 1917, a spontaneous revolt against the war spread throughout the country. The Czar was forced to abdicate and a new “provisional government” attempted to take power.

President Woodrow Wilson, who had won re-election in 1916 by promising to keep the U.S. out of the war in Europe, went before Congress in April 1917 and demanded a declaration of war against Germany. Congress obliged and declared war on April 6, 1917.

Before Wilson’s “war to end all wars” was over, well over 100,000 U.S. soldiers died. At least twice as many were wounded. Over four million soldiers were mobilized, despite widespread opposition to the war and the draft.

In October 1917, with the Great War still raging, the Russian people rose up again. This time they overthrew the “provisional government” that had maneuvered to continue Russian participation in the war. The Russian people had had enough, and put the Bolsheviks – firm opponents of the war – in power.

The slaughter of the Great War ended when a revolt spread throughout Germany, forcing the Kaiser to abdicate. Germany surrendered on November 11, 1918. The war officially ended in June 1919, with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles. We know now that this treaty only laid the basis for the even greater slaughter of fascism and World War II, and the wars that followed.

HEROES GROVE

On Memorial Day on May 30, 1919, thousands of people gathered in Golden Gate Park to dedicate a 15-acre plot as the “Grove of Heroes,” in remembrance of the U.S. dead and wounded in the Great War. Many of the estimated 12,000 mourners were dressed in black. The mourners created what the San Francisco Chronicle described as a “towering obelisk of flowers and wreaths.”

The Chronicle also reported that Mayor James “Sunny Jim” Rolph “committed the grove to the protection of the United States Army, Navy and Marine Corps.” Officers of the Army, Navy and Marines accepted that charge.

Today, there are no markers to tell the visitor to the park where or what Heroes Grove is. There is a dirt footpath through the grove, but the only signs are a couple of “Stay on Path” warnings.

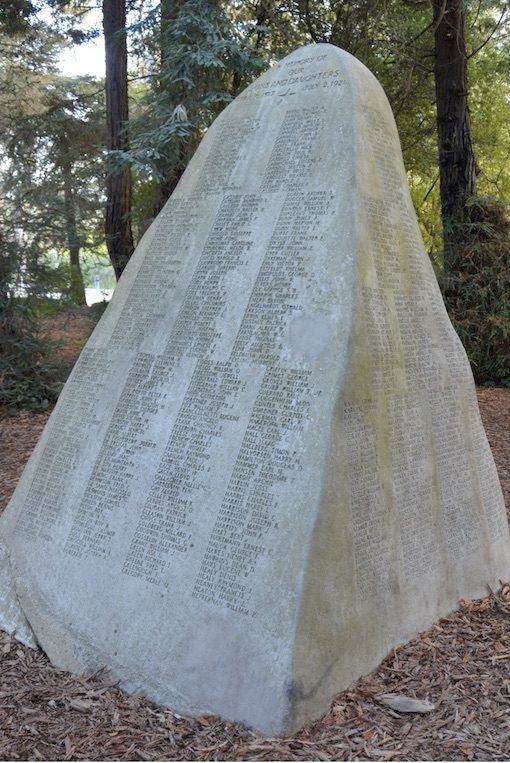

On Armistice Day (now known as Veterans Day) on November 13, 1932, there was another assembly in Heroes Grove. This time the gathering was to dedicate a new monument to U.S. war dead. The monument is an 18-ton granite boulder, reportedly quarried from Twin Peaks. The monument is inscribed with the names of 748 men and 13 women, all local soldiers and volunteers who died in the Great War.

Before the list of names is a simple inscription that reads:

The fighting in the Great War supposedly ended in 1918. The Treaty of Versailles was signed in 1919. So what does the 1921 date on the Gold Star Mothers Rock mean? More on that later, along with its relevance to the Russian Revolution.

So, where are Heroes Grove and the Gold Star Mothers Rock?

Transport yourself to Fulton Street and 10th Avenue. Here you will find the entrance to the park’s underground parking lot (a controversial pet project of the late Warren Hellman of Hardly Strictly Bluegrass fame). Behind the sign to the parking lot you will find an obscure, unmarked and unpaved footpath. This path will lead you into Heroes Grove.

Alternately, you can walk along the paved path on the north side of John F. Kennedy Drive, the northern road through the park, until you look down into the drive into the garage. Across the street is the obscene de Young Museum tower. Just to the west of the drive into the garage you will find another unmarked, unpaved footpath that will also lead you into Heroes Grove.

Whichever way you enter the grove, a little way along the path, look to your left. There you will see the Gold Star Mothers Rock.

You could walk along Fulton Street or John F. Kennedy Drive and just barely glimpse the Gold Star Mothers Rock through the trees, if you pay close attention. Thousands of people pass by every week and never notice. Think on that. This is a memorial to 761 people who died in World War I. Heroes, or perhaps victims, in the “war to end all wars.” This is their public marker. This is the glory that they have been granted.

You can also find the Gold Star Mothers Rock from an even more obscure, informal, unpaved footpath that enters the park from Fulton across from 11th Street, if you do not want to be bothered with any unnecessary steps through Heroes Grove.

My grandfather on my mother’s side fought in the Great War. I have heard stories of gas attacks, and of him floating in the Atlantic awaiting rescue after his ship was sunk. He is long gone, and I don’t know what was true and what was not. He was from Illinois, so he was never a candidate for the Golden Gate Park monument, and in any event he survived. If he had not, I would not be writing this. If my grandfather had not survived, my mother would not have married another veteran, who served honorably in the next war, that one a just and necessary fight against fascism. He also survived and amazingly enough is still alive today at the age of 100.

Nor, if my grandfather had not survived, would I have had an opportunity to tell the masters of war to go to hell when they attempted to put a gun in my hand and send me to Vietnam. War seems to have been the constant in the 20th century, and looks to be the same in the 21st.

Once you have spent some time with the Gold Star Mothers Rock memorial, remembering the veterans of World War I, you can return to the footpath, and continue west. You will walk through the forest for a little distance, and perhaps (or perhaps not) heed the warnings to stay on the path. Eventually you will come to the end of Heroes Grove and encounter the freeway-like Park Presidio Bypass Drive through the park. Here you can exit Heroes Grove, turn left and enjoy the Rose Garden, a much better-known and more-accessible feature of the park.

OUTSIDE HEROES GROVE: THE DOUGHBOY STATUE

After passing through the Rose Garden you can return to the John F. Kennedy Drive path, and walk on until you come to the Redwood Memorial Grove, across from the entrance to Stow Lake. In a clearing to your right you will see a more prominent World War I memorial, the Doughboy statue.

The Native Sons and Daughters of the Golden West planted 39 saplings and this statue in 1930, to commemorate some of the U.S. soldiers who died in the Great War, and in the Spanish-American War (the 1898 war in which the U.S. took possession of the Philippines, Guam, Cuba and Puerto Rico). The 39 saplings matched the 39 names memorialized on the plaque below the statue, all of whom were members of the Native Sons. This is a subset (not counting the Spanish-American War dead) of the hundreds of dead memorialized two years later on the Gold Star Mothers Rock.

In 1951, the names of 16 members of the Native Sons who died in World War II were added to the Doughboy plaque. No one has added any names of the many dead from the many wars the U.S. has fought since the end of World War II. I expect that there were some Native Sons killed in Korea, Vietnam, Iraq and Afghanistan.

You can now retrace your steps back to the de Young Museum tower. You can enter the tower for free. From the 9th floor, you can look out to the north over Heroes Grove. But, unless you already know what you are looking for, you will have no idea what you are looking at. There is nothing in the tower that even hints at the existence of Heroes Grove right below your feet. Nor can you see the Gold Star Mothers Rock from the tower, as it is hidden below the trees. After you enjoy the view, you can go downstairs and spend umpteen bucks to look at art from all over the world.

U.S. FIGHTS THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION

If you go back the same way you came, and pass by the Gold Star Mothers Rock again, you can contemplate why the inscription marks the end of the Great War as July 2, 1921.

The reason is that the U.S. Senate refused to ratify the Treaty of Versailles. Many senators were opposed to U.S. participation in the League of Nations, the forerunner of the United Nations, that was established by the treaty. The result was that it was not until 1921 that Congress passed a resolution officially ending U.S. participation in the war. President Warren G. Harding signed that resolution on July 2, 1921.

This would be only a historical footnote but for the fact that some U.S. troops continued to fight long after Germany had surrendered. But they weren’t fighting Germany. They were fighting Russians, in a useless attempt to overthrow the new Russian government and defeat the Bolsheviks. Wilson ordered two strategic armed interventions against the Russian revolution.

One such intervention has been dubbed the Polar Bear Expedition. A force of 5,000 troops were landed at Archangel in Northern Russia in September 1918, in support of British and French expeditionary forces that hoped to raise a White Army to defeat the Red Army organized by the Bolsheviks, and restore the eastern front. Some sources report that up to 8,000 U.S. troops were ultimately involved. It soon became obvious that the mission would fail, but the U.S. continued fighting through July 1919. Estimates are that nearly 250 U.S. troops died in this campaign.

The other intervention was in Siberia, the extreme eastern part of Russia. Here another 8,000 U.S. troops fought – along with troops from Britain, Canada, China, Italy and Japan – in the same vain attempt to kill the Russian Revolution in its infancy. This campaign started in August 1918, and went on until April 1920. Close to 200 U.S. troops died on this futile battlefront. Japanese troops stayed on fighting the Red Army until late 1922.

You don’t hear about Wilson’s war on Russia in your history class. If it were taught, it would help to explain the Russian Revolution’s antipathy to the U.S. and the Western powers in general. But, no, we learn instead that the U.S. represents the good guys and the Russians the bad guys, then and forever.

Were any of the U.S. soldiers killed in these Russian campaigns from the environs of San Francisco? Do their names appear on the Gold Star Mothers Rock? I don’t know. Maybe some family members know, or used to know. Maybe in this day of the internet somebody could research the 761 names on the memorial and find out.

But what matters is that the 1921 date on the Gold Star Mothers Rock takes on a new meaning because of these failed interventions. The Great War did not end in 1918, or even in 1919. It went on in a very literal sense. Soldiers died, Russians died, and the unremitting hostility of the U.S. toward the nascent Soviet Union led to many thousands and millions more deaths – enough for many, many more Gold Star Mothers memorials.

WAR MEMORIAL VETERANS MONUMENT

The mothers who instigated the creation of the Gold Star Mothers Rock had hoped that the monument to their sons and daughters would be installed at a place of prominence in the City, specifically on Van Ness Avenue between the War Memorial Opera House and the War Memorial Veterans Building. Cornerstones for both of these buildings were laid in 1931, and the buildings themselves completed in 1932. The expansive open space between these two buildings must have seemed like the obvious and natural place for the Gold Star Mothers Rock.

But, as ABC Channel 7 news later put it, “money and other priorities got in the way.”

There is an unsigned, undated, two-page lament in the archives at the San Francisco Public Library that reads in part:

There is another memorial spot set aside for the veterans of 1917-1918 which I visit on Memorial Day… We start at 10th Avenue and take a horse path going west among a group of trees. We proceed about 100 yards and presently to our left is a block of stone… [I]s this not a strange place for such a memorial?

Surely their mothers, who brought them into the world, did not select this place on a horse trail in Golden Gate Park… Originally, when the Golden Star Mothers contracted for this memorial and paid for it, the idea for its final resting place was the beautiful little park on Van Ness avenue between the War Memorial Opera House and the Veterans of World War I Building…

The Gold Star Mothers naturally assumed that since the citizens of San Francisco had voted bonds to the amount of five million dollars to erect these two buildings as a joint memorial to their sons and daughters, their memorial would be welcome.

But it was not to be. It seems the powers then in authority ruled that the Veterans Memorial did not want it, and said so. They declared it crude and inartistic. By no stretch of the imagination could that unsightly block of granite conform to the artistic pattern of these two gems of architecture. The poor little broken-hearted mothers evidently had no friends to plead their case, and so their precious little memorial was trucked off to the park and there it rests.

It was another 82 years before the “powers in authority” got around to placing a memorial to veterans in the space between these “two gems of architecture.”

In 2014, a memorial was dedicated after a private fund-raising campaign led by none other than Ronald Reagan’s former Secretary of State George Shultz.

Prior to going to work for Reagan, Shultz was President of Bechtel Corporation, the country’s largest construction and engineering company, which does business in every corner of the world. Bechtel, a private firm based in San Francisco, is widely considered a war profiteer for reasons far too numerous to detail in this article.

Shultz presided over the Reagan administration State Department from 1982 to 1989, throughout the period of the Reagan administration’s support for the illegal and savage Contra war against the Sandinistas in Nicaragua, who had overthrown dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle. Shultz returned to the Becthel Corporation as a director and senior counsel after he retired from the State Department. Schultz was an early and strong backer of George W. Bush’s campaign for the Presidency, and actively supported his 2003 invasion of Iraq. In 2012, the American Academy in Berlin awarded Shultz with the prestigious Henry A. Kissinger Prize.

The words “war criminal” easily come to mind when thinking about Schultz.

According to San Francisco’s El Tecolote newspaper, $1.5 million of the $2.5 million raised by Shultz for the 2014 veterans memorial came from the Stephen Bechtel Fund. Stephen Bechtel is currently the co-owner of the Bechtel Corporation. El Tecolote called this “blood money.”

The understated new veterans memorial sits on the eastern end of an expanse of grass, facing City Hall. There are no names of any veterans, alive or dead, on the memorial.

Actually there is the name of one veteran on the memorial, that of Archibald Macleish. Macleish was a poet and writer who saw action in World War I. He later found himself in the crosshairs of J. Edgar Hoover and his pal Joseph McCarthy. Macleish’s name appears under a poem inscribed in the center of the memorial, titled “The Young Dead Soldiers Do Not Speak.”

As Macleish says in his poem, “Our deaths are not ours; they are yours; they will mean what you make them.”

And so the “powers in authority” have chosen to give meaning to these deaths by naming the drive that surrounds this memorial on three sides the “Charlotte & George Shultz Horseshoe Drive.” This is certainly as ironic a memorial as naming Embarcadero Plaza after the racist Justin Herman. But unlike that tragic name, Shultz Horseshoe Drive remains like a bleeding scar in the heart of San Francisco.

Between the veterans memorial and Franklin Street lies an open sward of green grass. On the other side of Franklin Street is the eastern end of Fulton Street. It is a nearly-straight shot of about three miles up Fulton to the Gold Star Mothers Rock, hidden and nearly forgotten.

We forget the soldiers who have died in U.S. wars at our peril, and at the peril of the lives of our sons and daughters.

The grassy area next to the War Memorial veterans monument seems to be used these days primarily as a dog park. There is plenty of room on the grass there for the Gold Star Mothers Rock, which actually has names of veterans who died in the “war to end all wars.” Maybe someday the “powers in authority” will acquire the political will to move the Gold Star Mothers Rock memorial to the place where it should have been for these last 85 years.

All photos by Marc Norton.

Copyright © 2017 by Marc Norton.