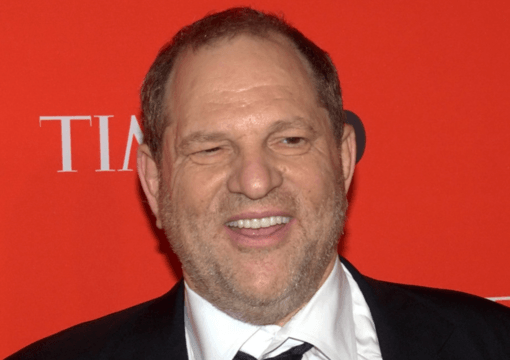

Photo by David Shankbone | CC by 2.0

A serious problem in America is the gap between academe and the mass media, which is our culture. Professors of humanities, with all their leftist fantasies, have little direct knowledge of American life and no impact whatever on public policy.

― Camille Paglia, author of Sexual Personae (1990) and Sex, Art, and American Culture (1992).

I’ve waited two weeks since news about Harvey Weinstein’s malignant power exploded in the New York press. How long do I hesitate before joining the debate, a debate that expand, drawing in more people, searching all levels of our culture which this occasion demands?

I suppose every woman, young or old, ambitious or docile, abused or not by a man– by anyone, perhaps herself an accomplice in abuse— has something to contribute here.

But what happens after the ten millionth testimony is proffered? After the trauma is identified? Does it help to say I too am a member in the same shamed and traumatized club along with Olympic champions, film stars and directors, fashion designers, and celebrity journalists as well as secretaries and research assistants, clients and patients? Does it help to confess, to listen, to empathize, to embrace a confessor, or to expose a predator? In the short term, perhaps. In the long-term, unlikely.

Does it help to disguise my feminine lines, veil my breasts, lower my gaze, and extinguish my body odor with mint flavored salve? Is it liberating to confide to my mother or sister, teacher or psychologist exactly what that rat did to my body, to recall my first experience of being violated, the unarticulated shock of what powerlessness really means? I doubt it. In the end, at the cultural-institutional level, none of these are remedial.

Where do we go after all the confessions are in, after the tweets have gone viral, after all the molestations are quantified, even after a court conviction?

I see no solution on the horizon. Because we are inextricably bound into a culture which celebrates the body, male and female. Our civilization encourages full explorations of sex, rewards ambition, and, most of all, it glorifies power, especially if that power is attached to wealth. These ideals are unassailable and no one is suggesting they be expunged.

This condition is evidenced by the abysmal record, near failure, of the very campaign that claimed to solve women’s problems—the Western feminist movement. A movement moreover, which, sanctioned by the UN, proudly and energetically exported itself to every corner of the world. Instead of weakening the patriarchal, misogynist culture that grips America at home, feminists of the 1980s adopted the paternalistic mantle they claim they had shed. Thus misguided, they set out to teach the world about true (women’s) democracy. I recall in the late 1980s, after the “opening” of China, a US press notice announcing progress in China:–a beauty pageant was planned in the communist state; multiple shades of lip paint were available to China’s women. China was advancing!

I do not recollect newly liberated American feminists applauding advances in civilization when women in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Philippines or Argentina won presidential office.

After the Middle East and Islam became topical in the 1990s, western women ignored their own unfulfilled goals to become global protectors, setting their sights on naughty men who mistreat Kurd, Afghan, Arab, Dalit, or Yazidi women. Feminism gladly brandished its new cudgel to strike at anything in the vicinity of Islam.

What might help reform the entrenched misogyny that’s been exposed in the Weinstein scandal is this: explore how and why we– young men as well as women– are attracted to power; why our self esteem depends so much on our beauty, being gazed at. Why do we dash after anything that ‘goes viral’? Why do we want far more money than we need to live? Why can we not say “No” to a cleric’s advances, to a sport star’s invitation, to a boss’ wink, to promises of greater success?

A feature of youth is short attention span; this could apply to youthful America, with its tendency to believe that when its wrongs are revealed, it expresses remorse and then moves forward. Having admitted its misdeeds, it matures. Alas, this is not America’s way. It coats itself in cosmetic confessions. For an example of our enduring immaturity, look at the hugely popular TV series, “Mad Men“. I completely missed “Mad Men” from 2007 to 2015 when millions of Americans followed its weekly episodes. Being a media critic, however belatedly, I set out to examine the source of its acclaim. So I began viewing “Mad Men”. That was last month, before the Weinstein exposé ignited the debate about sexual predators. Discussing the “Mad Men” phenomenon with others, we recalled how poignantly the series portrayed verbal and physical debasing of women by husbands, lovers and office colleagues. “Yes, that was how men behaved in the sixties; that’s what women accepted. It was the culture then (before the feminist movement). Men couldn’t get away with that now.” Can’t they? “No. Well it’s more subtle, more circumspect, today.” Is it?

If you live in rock and roll, as I do, you see the reality of sex, of male lust and women being aroused by male lust. It attracts women. It doesn’t repel them.”

― social critic, Camille Paglia

We have to recognize that the foundation of our culture, dominated as it is by male energy and sexuality, remains intact. This, despite some cosmetic and legal adjustments. How much are women willing to risk in their search for esteem and other rewards.

Sexual abuse and harassment of women must be viewed within a wider portrait of this unwholesome nation. Progress has faltered on many fronts: we’ve returned to Jim Crow incarceration and racism we believed was far behind us, a condition documented by civil rights lawyer Michelle Alexander. Human trafficking, approaching slavery, is rife. Child abuse and kidnapping continue; pornography has surged with the application of digital tools. Rape of women by the military is carried out against captives but also fellow soldiers. And we all know something about torture in the 21st century.

Back to the ‘Weinstein problem’: the press continues to engage us with yet more stories of celebrities’ encounters with this pervert. Yes, just like fellow media moguls Bill Cosby and Roger Ailes. But surely this is part of a ‘cultural condition’ we’ve known about and debated for some time, e.g. campus rape, the violation of women by fellow college students. Like Hollywood insiders, university authorities ignored or minimized the violence. They treat the scourge by referring cases not to police but to college grievance committees. A 2015 film treatment of the issue does not indicate the problem is solved. University cover-ups, we learn, serve to maintain a reputation attractive to philanthropists.

The ongoing problem of sexual abuse of women (on campus or in the film and TV industries) was a subject of acerbic exchanges among feminists 30 years ago. On one side, almost single-handed—the “anti-feminist feminist” culture and art critic– Camille Paglia boldly took on mainstream feminists. In a sustained series of exchanges, many of which appear in her 1992 collection Sex, Art and American Culture she declares, “Feminists keeps saying the sexes are the same…telling women they can do anything, go anywhere, say anything or wear anything.

“No they can’t.” Paglia exclaims. She attacks what she sees as mostly white, educated feminists for their “pie-in-the-sky fantasies about the perfect world (that) keep young women from seeing life as it is.” As a result, she argues, “Women want all the freedoms won, but they don’t want to acknowledge the risk. That’s the problem”.

I’d like to hear Paglia’s take on today’s debate around the Hollywood scandal (it’s bigger than one disgraced pervert). She might help us more fully explore issues of risk and responsibility, not men’s– women’s. How can that be taught? Children are supervised ever more closely via their cell phones. Can this prepare them too handle risks as adults, faced with predators like Weinstein?