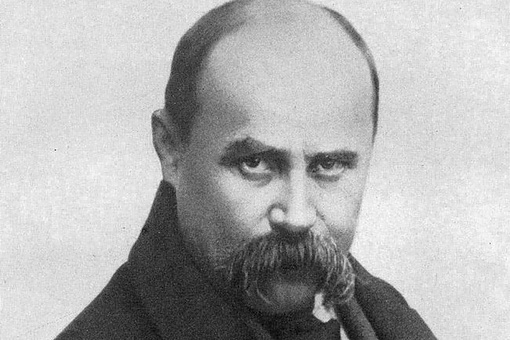

In the pantheon of “fathers of nations” of any European country, there are eminent poets who expressed the spirit of their nation and shaped its national language and imaginary. Shakespeare in England, Robert Burns in Scotland, Villon and Rabelais in France, Adam Mickiewicz in Poland, Goethe and Schiller in Germany, Pushkin in Russia. In Ukraine, such a national figure is Taras Shevchenko. [1]

Early years

He was born into a peasant family in a village of Cherkasy oblast in the Kiev gubernia (governorate) in 1814. Shevchenko’s family were serfs on the land of Count Vasiliy Engelhardt, a Russian aristocrat and landlord. Shevchenko’s father was literate, he sent his son to be educated as an apprentice to a deacon.

An orphan by the age of eleven, Shevchenko spent his childhood working as a houseboy and training to be a servant. He had a gift and passion for painting, which he would pursue during his leisure time.

When Shevchenko turned 14, he became a domestic servant to Count Pavel Engelgardt, the son of Vasiliy Engelhardt. Shevchenko stayed with his master in Vilnius from 1828 to 1831 and then moved to Saint-Petersburg. Count Engelgardt, who noticed and encouraged Shevchenko’s painting talent, sent him to an apprenticeship for four years with a well-known painter. During his leisure time, Shevchenko sketched the statutes in the imperial summer gardens of St. Petersburg.

In St. Petersburg, Shevchenko met compatriots from Little Russia–‘Malorossiya’, as Ukraine was called at that time in the Russian Empire. They introduced him to the circle of Russian artists and poets, including the famous painter and professor, Karl Briullov, and poet Vasiliy Zhukovskiy. They took to heart Shevchenko’s great talent and decided to purchase his freedom from serfdom. Karl Briullov painted a portrait of Zhukovskiy and donated it as a prize in a lottery to raise money for the payout. In the spring of 1828, Shevchenko became a free man.

Soon after, he was accepted as an external student into the Imperial Academy of Arts under Briullov’s supervision. In 1840, Shevchenko’s first poetry collection, ‘Kobzar’, was published in St. Petersburg. It received positive reviews from Russian progressive intelligentsia. Kobzar revealed Shevchenko’s outstanding poetic talent. His language “sparkled with a clarity, breadth and elegance of artistic expression not previously known in Ukrainian writing”, as another famous Ukrainian poet, Ivan Franko, would write later. Kobzar was followed by other poetic works.

While living in St. Petersburg, Shevchenko made three trips to Ukraine in the period of 1843-1846. These trips had a profound impact on him. He saw the difficult conditions of serfdom in which his still-enslaved siblings and relatives lived. In Kyiv, he met with prominent Ukrainian writers and intellectuals Panteleimon Kulish, Evhen Hrebinka and Mykhaylo Maksymovych. Shevchenko was distressed by the social and national oppression of Ukrainians by tsarist Russia. This became one of the main themes of his poetry.

In March of 1845, Shevchenko graduated from the Imperial Academy of Arts with the title of artist, and in the fall of the same year, on an appointment of the Kyiv Archeological Commission, he left to paint the historical and archeological sites of Poltava region of Ukraine.

Political engagement begins

In the spring of 1846, while living in Kyiv, Shevchenko joined the secret political society ‘Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood’. Members of the society, prominent intellectuals of Ukraine (Malorossiya), set as their goal the liberalization of Russia according to Christian principles and Slavophil views. The society’s program included the abolition of serfdom; broad access to public education; transformation of Imperial Russia into a federation of free Slavic people with Russians as one of equals; and implementation of democratic principles of freedom of speech, thought, and religion.

Imperial Russian authorities could not tolerate such liberal views and in April of 1847 they arrested members of the Cyril and Methodius Brotherhood – the ‘Ukrainian-Slavic Society’, as it was called in the official report by Count Orlov to Tsar Nicolas I. Count Orlov stated in his report that instead of eternally nourishing feelings of reverence towards the royal family for having redeemed him out of serfdom, Shevchenko wrote poems of the most outrageous content in the ‘Malorossiyan’ language.

In his poems, Orlov reported, Shevchenko lamented the alleged enslavement and misery of Ukraine. The poet glorified the Cossack Hetmanate [2] and liberties enjoyed by Cossacks, and he wrote “slanderously” of the members of the imperial house. Orlov found Shevchenko’s poetry doubly harmful and dangerous because Shevchenko was gaining a reputation as a great poet. His poetry could spread and implant in Malorossiya the idea of bringing back the blissful times of the Hetmanate and the possibility of the existence of Ukraine as an independent nation and state.

As punishment, Shevchenko was assigned to military service as a private in the Orenburg Special Corps, stationed in a remote region by the Caspian Sea. Tsar Nicholas I wrote in his own hand on Shevchenko’s sentence: “Under the strictest surveillance, with a ban on writing and painting”. While serving in Orenburg and later in Orsk fortresses, Shevchenko managed to write in secret a book whose pages he kept in his boot.

Thanks to his skills as a painter, he was included in a military expedition to survey and describe the Aral Sea in 1949-1850. In 1850, he was transferred to the Novopetrovsk fortress in Kazakhstan, where in spite of strict discipline and rigorous surveillance, he was able to draw. He made over a hundred watercolours and pencil drawings and he wrote several novellas in Russian.

Shevchenko was released from exile in 1857, two years after the death of Tsar Nicholas I. He was not allowed to live in Ukraine, so he moved to St. Petersburg. In 1859, he was allowed to visit relatives and friends in Ukraine, but was arrested on a charge of blasphemy. He was interrogated, released and ordered to return to St. Petersburg.

Taras Shevchenko spent the last years of his life working on new poetry, paintings and engravings. He also edited his older works. He became a real innovator in engraving and in September of 1860, the Council of the Imperial Academy of Arts granted him the title of the Academician of Engraving.

His health, undermined by difficult exile, had begun to deteriorate. He died in St. Petersburg in his studio apartment on March 10, 1861, one day after his 47th birthday. At the funeral ceremony at the Academy of Arts, speeches were delivered in Ukrainian, Russian, and Polish. Shevchenko was first buried in St. Petersburg, but two months later, in accordance to his wishes expressed in the poem ‘Testament’, his friends reburied him on Chernecha Hora (Monk’s Mountain) near Kaniv on the Dnipro river, located 130 km to the south and east from Kyiv.

A national hero

Shevchenko has long been the most famous of Ukrainian poets and certainly the most loved one. He was truly a people’s poet. His poems are learned by heart in every Ukrainian school throughout the world, including in Russia. Ukrainians by origin and by heart travel to Shevchenko’s burial site like pilgrims to Jerusalem. Shevchenko is the spirit of Ukraine, the best of the poets to express the sufferings and hopes of ordinary Ukrainians.

Monuments to Shevchenko are erected in every city and town of Ukraine, including Donetsk and Lugansk in the east. Throughout the country, on the date of birth of the great poet, March 9, officials and ordinary people lay flowers at Shevchenko monuments and recite his poems in spontaneous gatherings.

The people of today’s Donetsk People’s Republic and Lugansk People’s Republic are no exception. That is precisely the point I want to make by analyzing the recent commemoration events for Shevchenko in Donetsk and Lugansk and the coverage of this event in some Ukrainian media.

Shevchenko honored in Donetsk

Ukrainian media and the majority of Western media portray Donetsk and Lugansk regions as being ‘Russian’. People in Donetsk and Lugansk are said to hate everything Ukrainian, which is why an act of laying flowers to Shevchenko’s monument in Donetsk, the media pronounces, amounts to an act of bravery.

A news item on the Ukrainian website UNN voices this distorted view. The item is titled, ‘Some bold-spirited people brought flowers to Shevchenko monument in Donetsk‘ and it reads, “Unknown activists in Donetsk honored the memory of the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko and laid flowers to his monument.” Saying its report is based on social media postings, UNN continues, “Today’s Taras in Donetsk. There are flowers at the monument, laid by some bold-spirited people. Donetsk is Ukraine! Happy birthday, Taras!”

I will not comment on the reliability of social media as a source for professional journalists, except to note that media in Ukraine often draws upon non-verified information from such sources.[3]

UNN could spare itself some embarrassment by reading this primary source, an article in Antifashist.com titled ‘Taras Shevchenko commemorated in DPR‘. I will sum up this article, which is written in Russian and which shows how far from the truth is UNN’s news item. The Antifashist article writes, “Students and young soldiers gathered around the Shevchenko monument in Donetsk on March 10 in front of the main government building. Music is playing; flags of the DPR are flying. Somebody is reciting poems.

“An old lady in a scarf asks the crowd, ‘What are you commemorating?’. Someone in the crowd replies ‘The anniversary of Shevchenko’s death.’ The older lady then says, ‘I am hearing good poetry. I have loved Shevchenko since I was a child.'”

The author of the article, Andrei Kostin, must be a local. He continues: “Shevchenko, a painter, a poet, a writer. Born in Ukraine, educated as an artist in St. Petersburg, bought out of serfdom with money raised by Russian intelligentsia. He has been and will always be loved and respected by cultured people of our city. His monument has been adorning our city for many years…”

“The event commemorating the poet was organized by students-activists of the DPR and a public organization, ‘Young Republic’. They organized the event by their own initiative, in spite of shootings and explosions during the night, the destruction of monuments in cities and towns and hateful speeches of fascist thugs…”

“According to the fascist thugs, anything even remotely connected to Russia, starting from books and films, must be destroyed…while we [people in Donetsk], without tainting culture in political tones, quote with pleasure Shevchenko, read Gogol and sing Ukrainian songs.”

The writer has a point. Donetsk has not rejected Ukraine as a culture, as a people. Commemoration of Shevchenko is tangible proof. Donetsk has not rejected Ukrainian culture or the Ukrainian people. Donetsk has rejected the nationalist ideology that was present in Euromaidan and has become the official ideology of the current political regime in Kyiv.

And honored in Lugansk

Another Ukrainian report on the commemoration of Shevchenko’s birthday is from Lugansk: ‘In ‘LPR’ flowers were laid to Shevchenko monument‘. This time, it is Ukrainian television station 112, the most popular TV channel in Ukraine today. Its report quotes the “separatist” Channel 24 in the Lugansk People’s Republic.

“Yesterday [March 9] in occupied Lugansk, flowers were laid at the Taras Shevchenko monument in Lugansk city. According to the so-called mayor of the city, Manolis Palavov, the ‘LPR’ is commemorating the 202nd anniversary of the poet’s birth.”

The language is typical of the language of Ukrainian websites: “occupied Lugansk”, the “so-called mayor”, “LPR”, etc. Other highly symbolic detail shown in the 112 report is that flowers in baskets were colored blue and red, the colours of the LPR and of Russia.

Lugansk Mayor Palavov also made a paradoxical statement. He said, “Shevchenko is a person who praised in his poems Russia and Malorossiya”. The mayor also noted that LPR authorities have no intention of dismantling the Shevchenko monument. “We honor history and invite the Ukrainian side to do the same”. Palavov was alluding to the destruction throughout Ukraine of monuments to Lenin and various prominent figures of the Soviet era during the past two years.

There is, indeed, a striking contrast between Ukraine and the DPR and LPR in this regard. In the Ukraine that so ardently destroys its Soviet monuments together with its industry, the past is rewritten to repudiate anything Soviet or Russian. The Ukrainian national project is officially proclaimed to be Unitarian and monist, with no tolerance for Russian as an official language. In Donetsk, the Soviet past is not only left intact, it is incorporated in the state building of the fledgling republic. And Donetsk and Lugansk are preserving their multinational, anti-ethnic and Russian-speaking identity.

Donetsk and Lugansk have not rejected Shevchenko. On the contrary, Shevchenko belongs to their cultural heritage. He grew out of Malorossiya, as did, later, Donetsk and Lugansk. Shevchenko was an ardent opponent of the tsarist regime, not of Russian culture or the Russian people. Donetsk and Lugansk people do feel close to Ukrainians of Central Ukraine culturally and linguistically. This link of kinship weakens as one moves farther west in the country, as studies on regional identities in Ukraine have shown.

For 25 years, since the early days of Ukrainian independence, political elites played on these regional differences instead of proposing a national project that would unite culturally diverse regions. Donbass is not anti-Ukrainian, no matter how hard the Ukrainian propagandist machine tries to convince the Ukrainian population of this. Donbass is not Russian neither. Its hybrid identity is not based on ethnicity.

Donbass is a melting pot in which many ethnicities have been fused into a Russian speaking regional identity, oriented culturally to Russia. In 25 years of Ukrainian independence, Donbass did not become Ukrainian in the spirit of right-wing Ukrainian nationalists, that is, as an anti-Russian Ukraine. Neither did Donbass become anti-Ukrainian. After all, the region shares 70 years of common Soviet history with Ukraine. The example of Shevchenko’s commemoration is an illustration of this. Another illustration is the fact that both languages, Russian and Ukrainian, are declared to be official languages of the DPR.

If only the current Kyiv regime did not try to impose on Donbass its exclusionist, nationalist ideology with its anti-Russian and anti-Soviet heroes, such as the WW2 Nazi collaborator Stepan Bandera. If only Ukraine let Donbass and other Ukrainians who share its views freely commemorate their Soviet heroes, their victory in the Great Patriotic War, and so on. If the new regime installed in Kyiv in February of 2014 had not tried to revoke the law on languages which provided Russian the status of “regional” language, Donbass may well not have rebelled. Shevchenko’s commemoration is a visible sign of kinship between Ukraine and Donbass, a tiny beam of hope that reconciliation is possible, at least at the level of ordinary people.

Unfortunately, the post-Euromaidan, pro-NATO regime in Kyiv is unwilling to engage in a true dialogue with Donetsk and Lugansk. Without that, no lasting peace will ever come to Ukraine.

Notes:

[1] The following biography of Shevchenko is based on the outline, provided on the website of the Shevchenko Museum in Toronto: http://www.infoukes.com/shevchenkomuseum/museum.htm

[2] Cossack Hetmanate (Hetmanshchyna), or Hetman State, was the Ukrainian Cossack state which existed from 1648 to 1782 in central Ukraine. It was founded by the Hetman, Bohdan Khelnytsky, during the revolt of the Cossacks against Polish rule. The Hetmanate was squeezed between Poland and the Russian and Osman empires. Bohdan Khmelnytsky asked the Russian tsar to incorporate the Hetmanate territory as an autonomous duchy under Russian protection. In March of 1654, the details of the Union were negotiated in Moscow. Cossack leadership of the Hetmanate, was divided over allegiance to Russia. In 1708, Hetman Ivan Mazepa undertook an unsuccessful attempt to break the union with Russia. Following Mazepa’s defeat, Cossack autonomy was significantly reduced. In 1764, the institute of Hetman was officially abolished by Catherine II of Russia and the Cossack Hetmanate was incorporated into the ‘Malorossiya’ Governorate.

[3] An exiled Ukrainian journalist, Anatoliy Shariy, does a great job of debunking such so-called news. Another odd habit in many Ukrainian social media and internet new outlets, including UNN, is the practice of citing themselves as news sources, written in the third person. UNN and other such news sources appear to believe that super-objectivity comes with talking about themselves in the third person.